Author: Boardman J.

Tags: art greek sculpture sculptures ancient greece arts classical art period world art

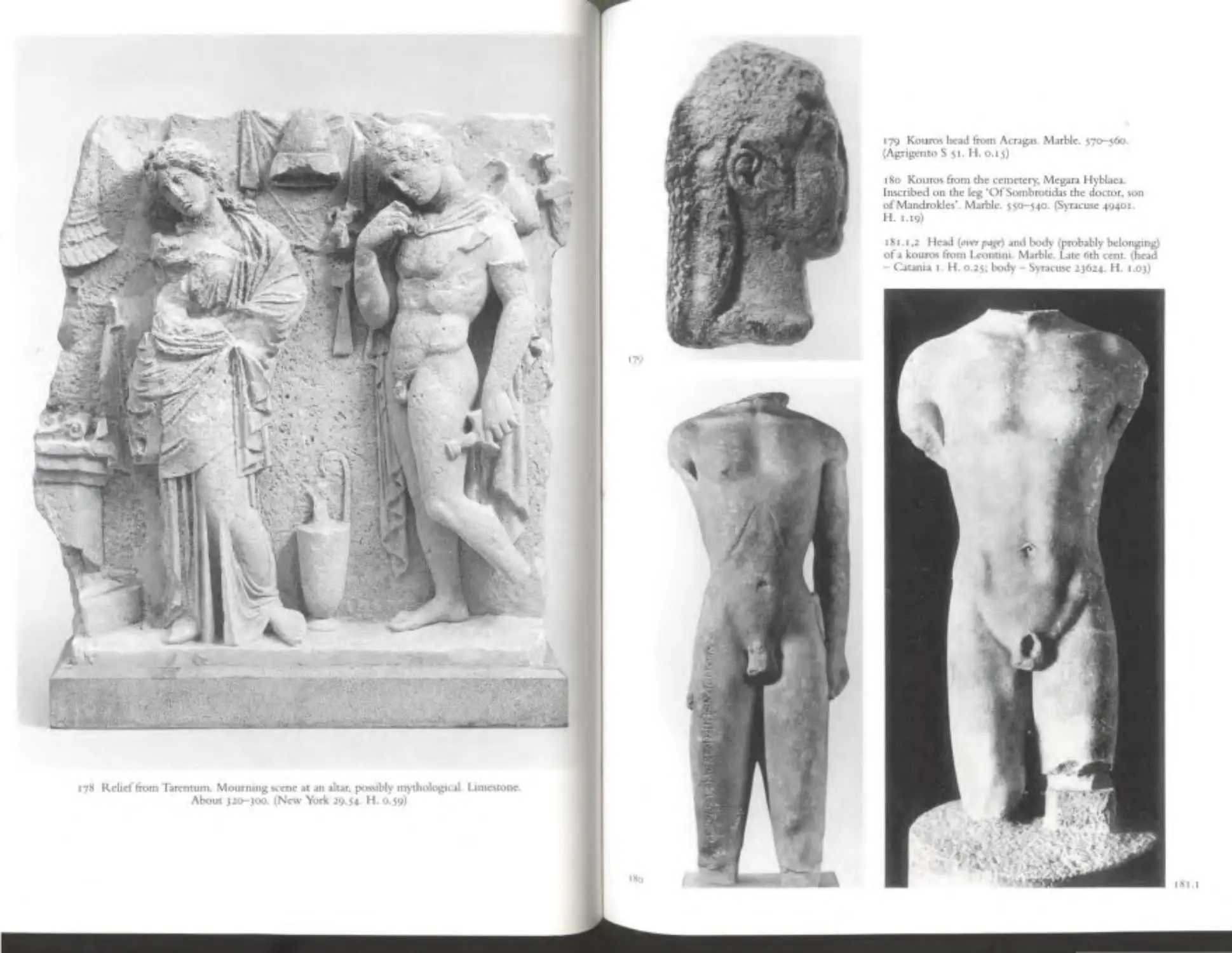

ISBN: 0-500-20285-0

Year: 1995

Similar

Text

I:-IN BOARDMAN

Sig

Sir John Boardman

was born in 1927, and educated at

Chigwell School and Magdalene College, Cambridge. H e

spent several years in Greece, three of them as Assistant

Director ofthe British School ofArchaeology at Athem, and

he has excavated in Smyrna, Crete, Ch10s and Libya. For four

years he was an Assistant Keeper in the Ashmolean Museum,

Oxford, and he subsequently became Read<r m Classical

Archaeology and Fellow of Merton College, Oxford. He is

now Lmcoln Professor Emeritus ofClasSical Archaeology and

Art m Oxford, and a Fellow ofthe llnush Academy. Professor

Boardman has written widely on the art and archaeology of

Ancient Greece. His o ther books in the World of Art series

include Greek Art; Atl~e11ia11 Black F(~11re vases; Athe11ia11 Red

Fig11re liJSts: 111t Archaic Period and ... '11~e Classical Period;

Greek Sculpwre: 111e Archaic Period and ...

111t Classical Period.

8

WORLD OF ART

This famous sene<>

provtdes the \vtdest available

range of illustrated books on art m all Its aspects.

If you would ltke to n:cetve a complete hst

of t1tles in print please wrue to:

THAMES AND IIUDSON

JO 131oomsbury Street, London, WC16 JQP

In the United States please write to:

THAMES A.NO HUDSON INC.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10110

Printed m Slovenl3

lt::t

Filozoficka fakulta UKOFIUK

3805 01050000257

Any copy of thos book ISsued by the publisher as a paperback is

sold subject to the conditiOn that 11 shall not by way of trade o r

otherwise be lent, reso ld, hired out o r otherwise circulated without

the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover o ther

than that m w hi ch lt lS pubhshed an d without a sim1lar condinon

mcluding these words bemg 1mposed on a subsequent purchaser.

0 1995 Thame> and H udson Ltd, London

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be

reproduced or tranmutt ed m any form or by any means, electronic

or mechamcal, mcludmg photocopy, recording o r any other

information storage and retrieval system, without prio r permission

in w riting fi-om the pubhsher.

Briti sh Li brary Catalogum g - m -Publicat1on Data

A catalogue record for thos book is avatlable from the British

Library

ISBN o-soo -20285-o

Printed and bound m Sloven ~a by Mladmska KllJiga

C ONTENTS

pref ·e

Part 1. Late Classica l Sculpture

4

6

INTRODUCTION

.

.

I d .,., hnt.qu e· Places Patrons and Plan nmg; Fmances

Styean .ec

•

•

ARCHITECTURAL SCULPTURE

NAM ES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

Atl •n an; Other

GODS AND GODDESSES, MEN AND WOMEN

O riginals _ bronzes, marbles; Copies

PORTRAITURE

FUM.RARY SCULPTURE

Athens and Attica; Non-Attic gravestones; Monuments;

Sar< ophagi

7 OTHER RELIEFS

Von· e; Record; Bases

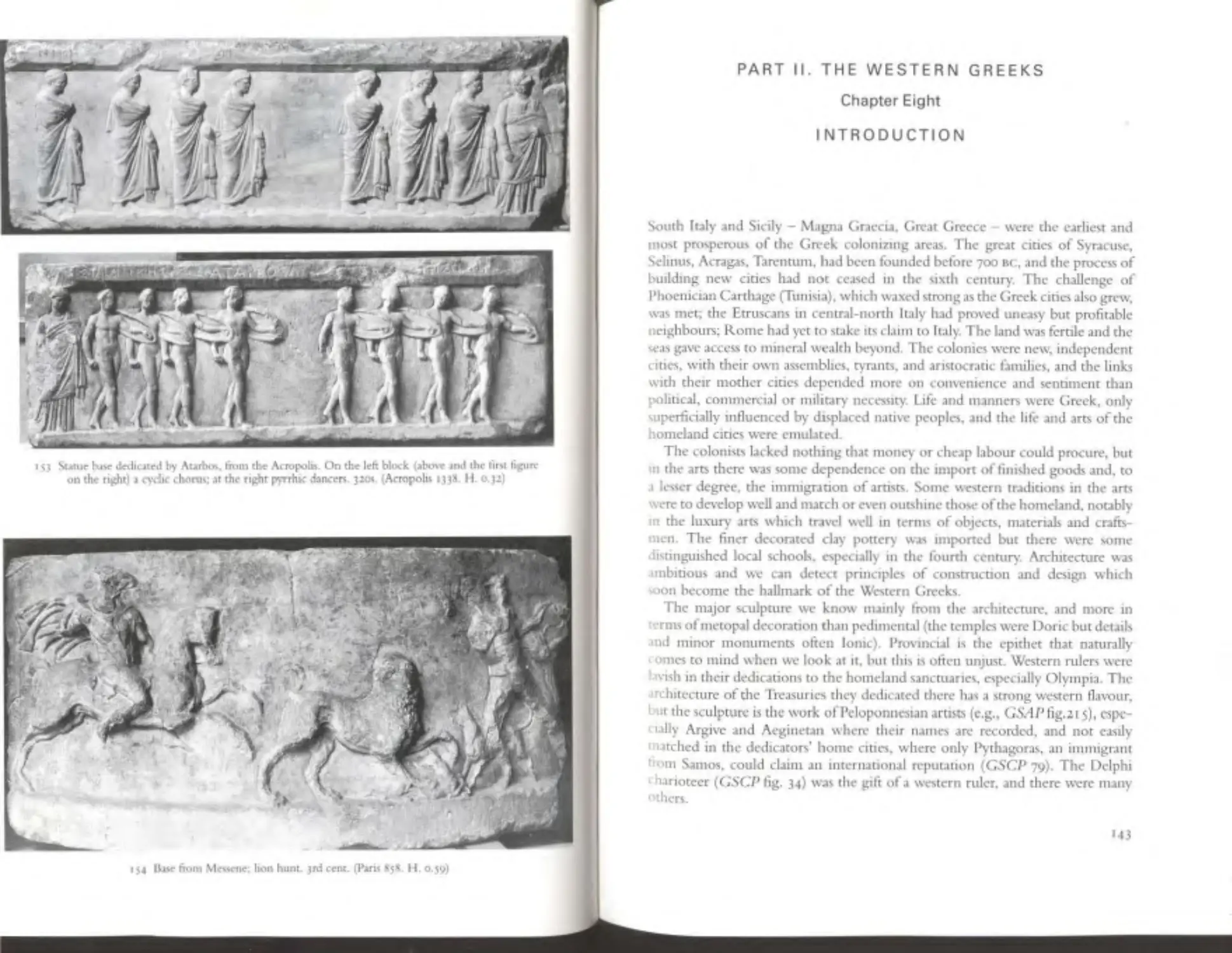

Part 11· The Western Greeks

INTRODUCTION

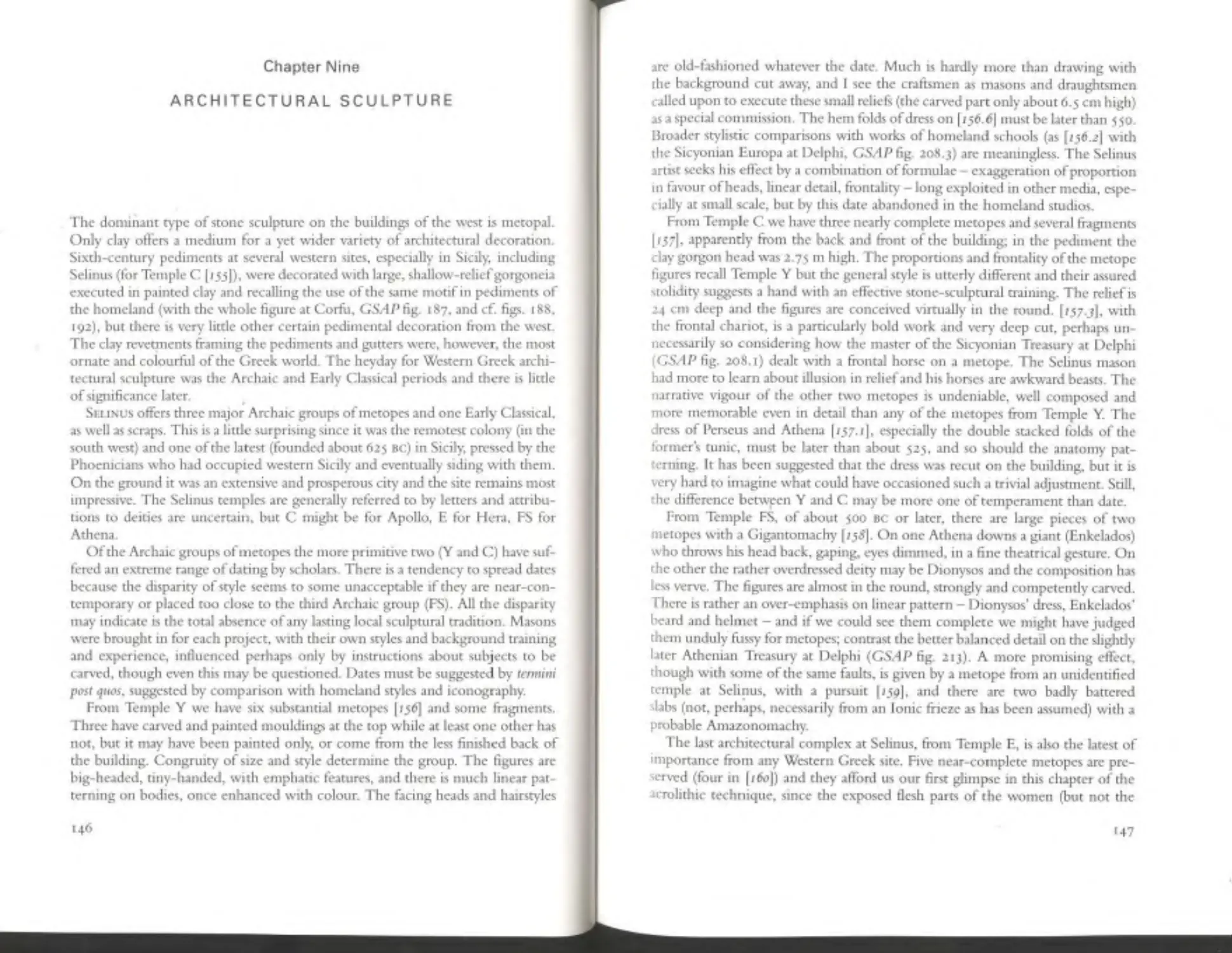

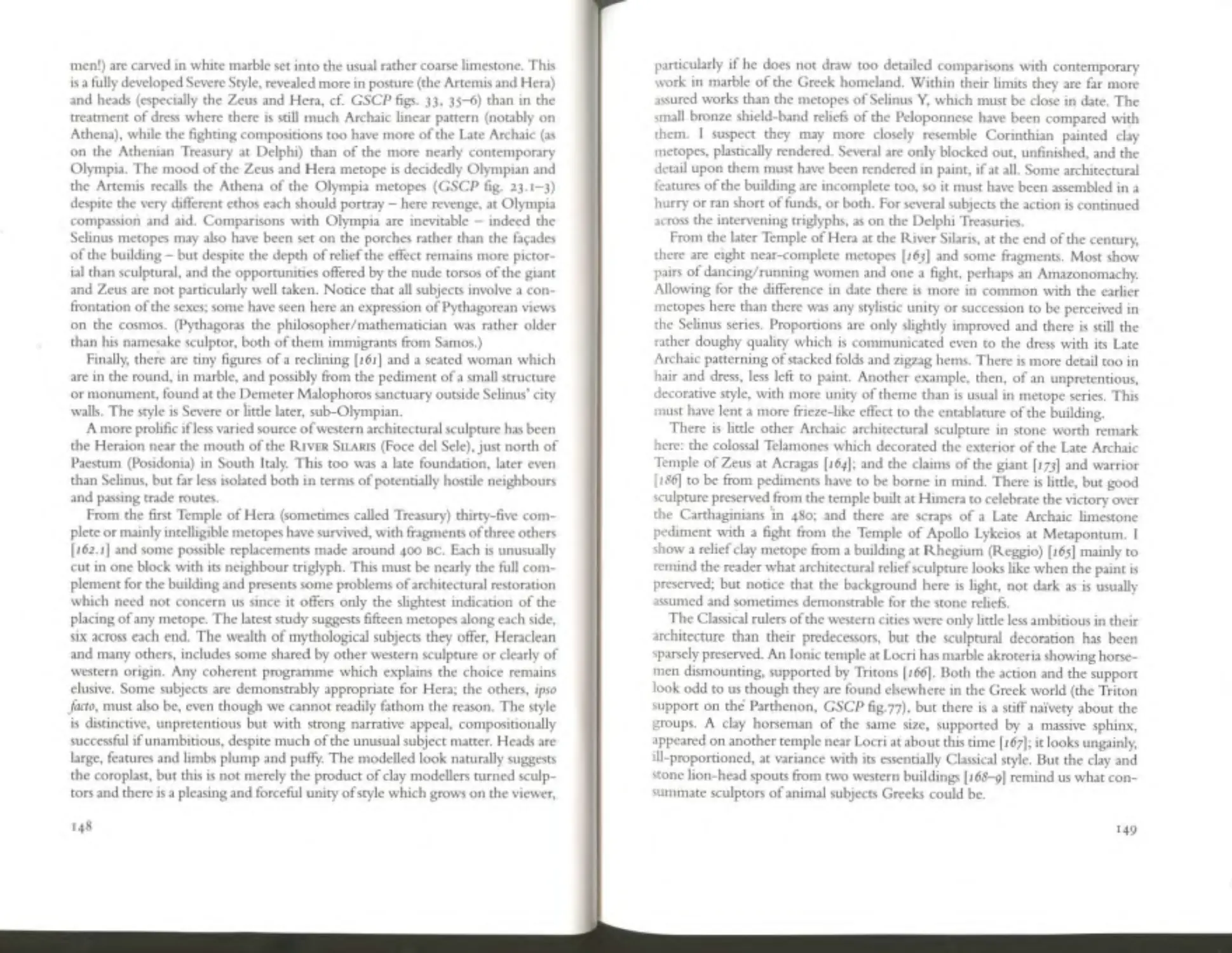

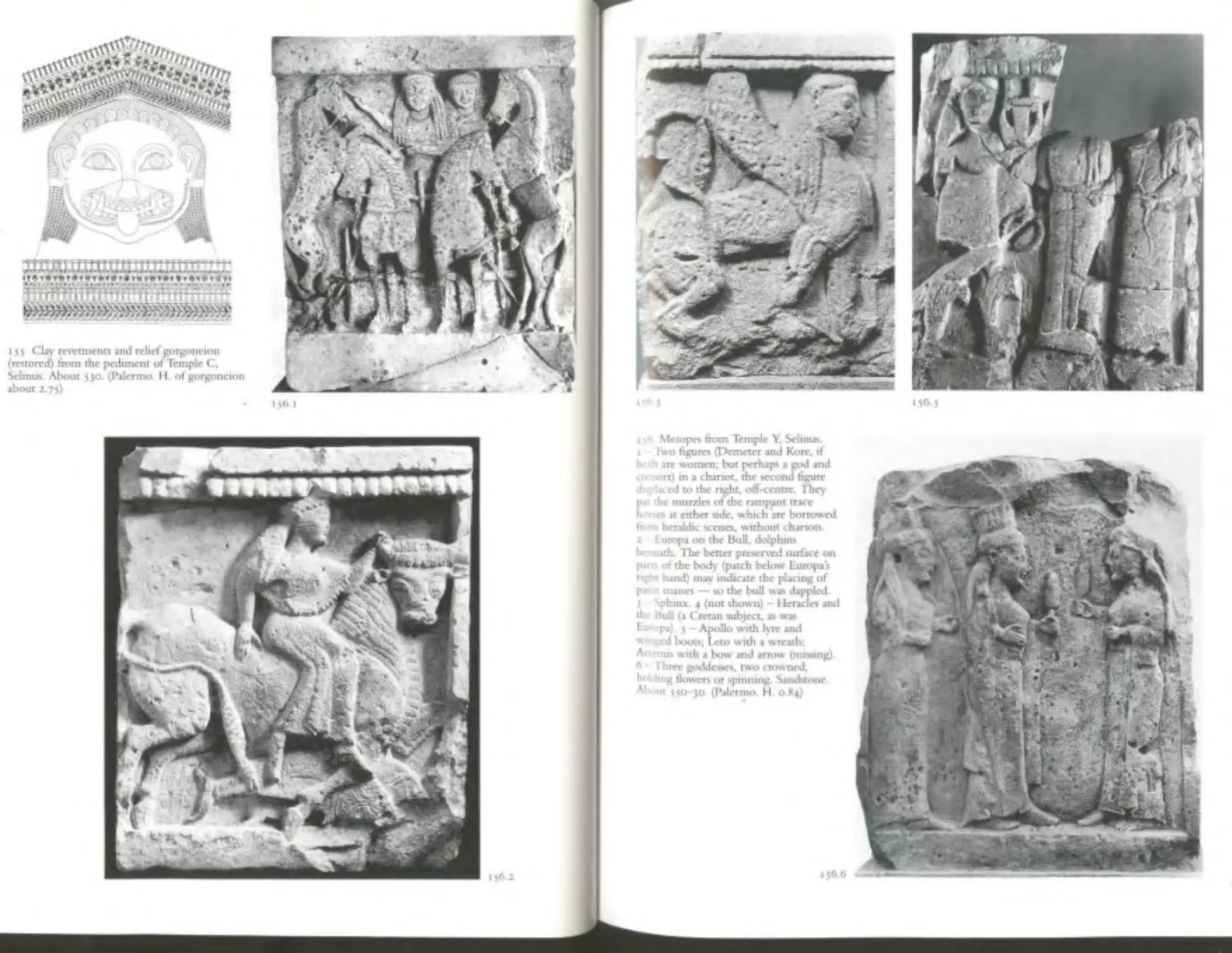

9 ARCH ITECTURAL SCULPTURE

1o OTHER SCULPTURE

.

Lo.. al stone; Marble; Acro li ths; Bronze and Clay; Etruna and

E:rl Rome

7

11

23

70

103

114

IJI

143

r62

Part Ill: Greek Sculpture to East and South

rr ANATOLIA

1 2 THE LEVANT AND NORTH AFRICA

Part IV: Ancient and Antique

13 COLLE CTING ANI) COLLE C TIONS

Antiqurty; Taste and the Antique; Status and the Antique·

Atrrtudes and th e Annque

'

Abbreviations

Notes and Bibliograph ies

Index of lllumations

Index o(Ancient Arti sts' Names

Acknowledgements

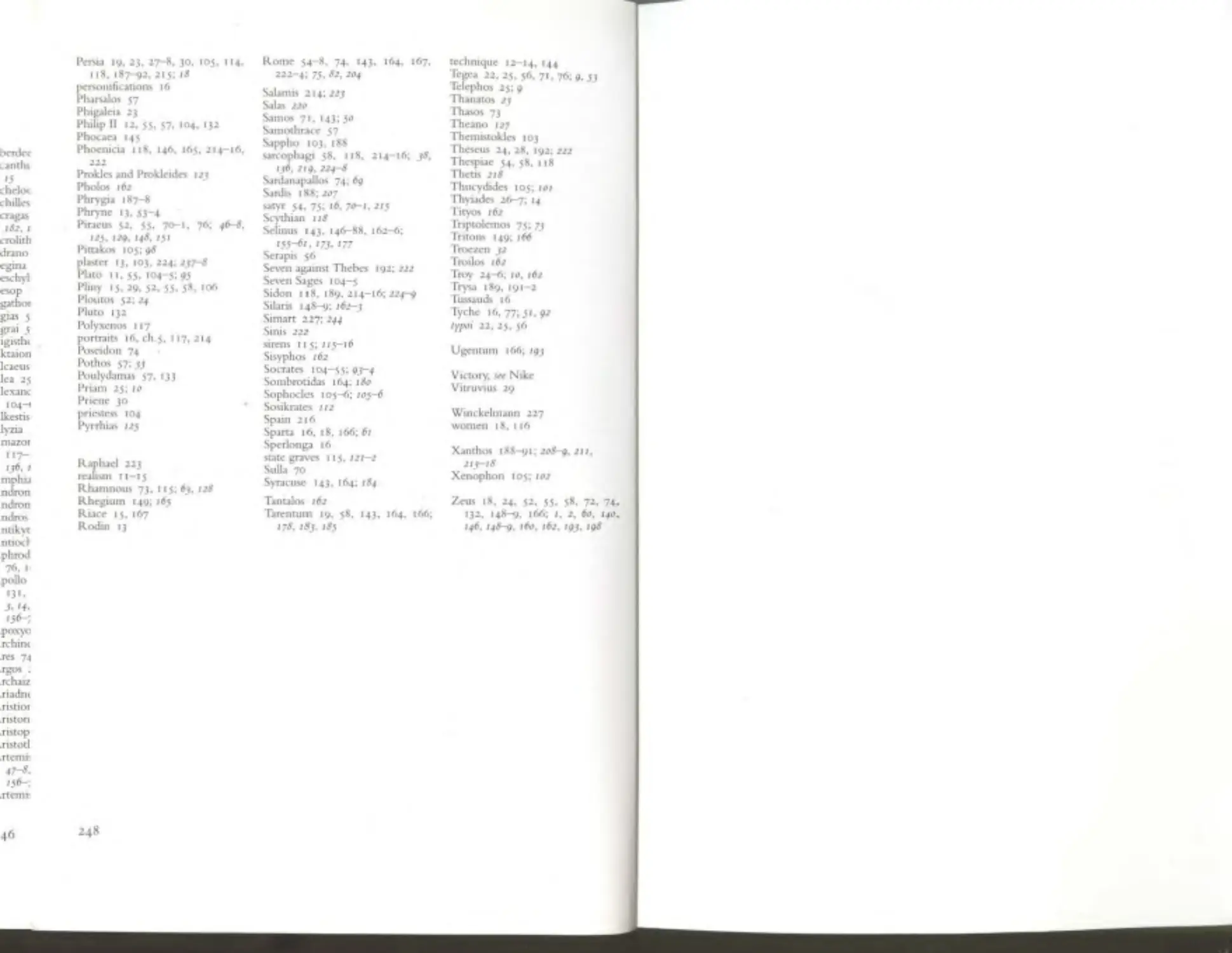

General Index

M APS

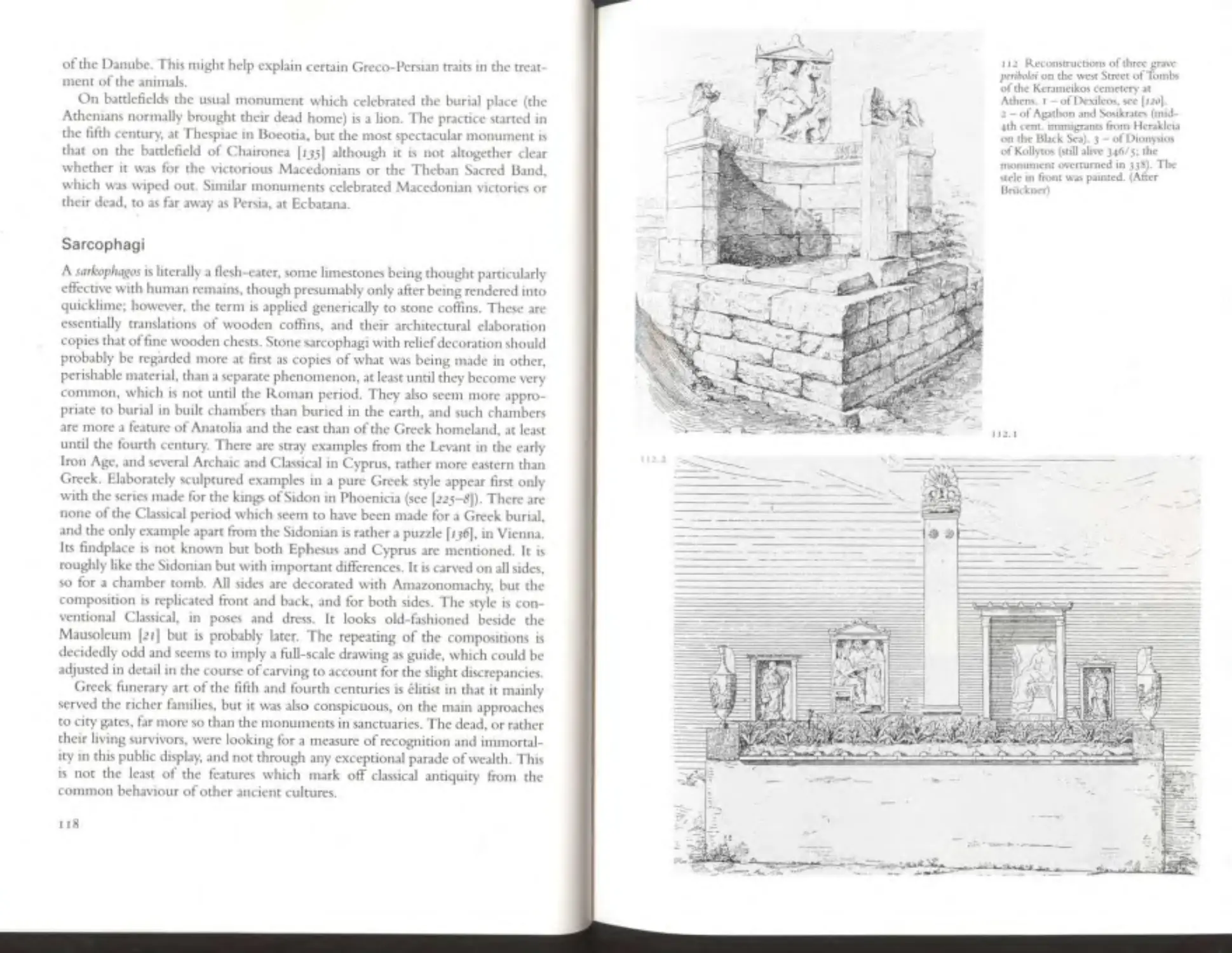

Greece a11d 171e Aegea11 World (pp. 2o-2r)

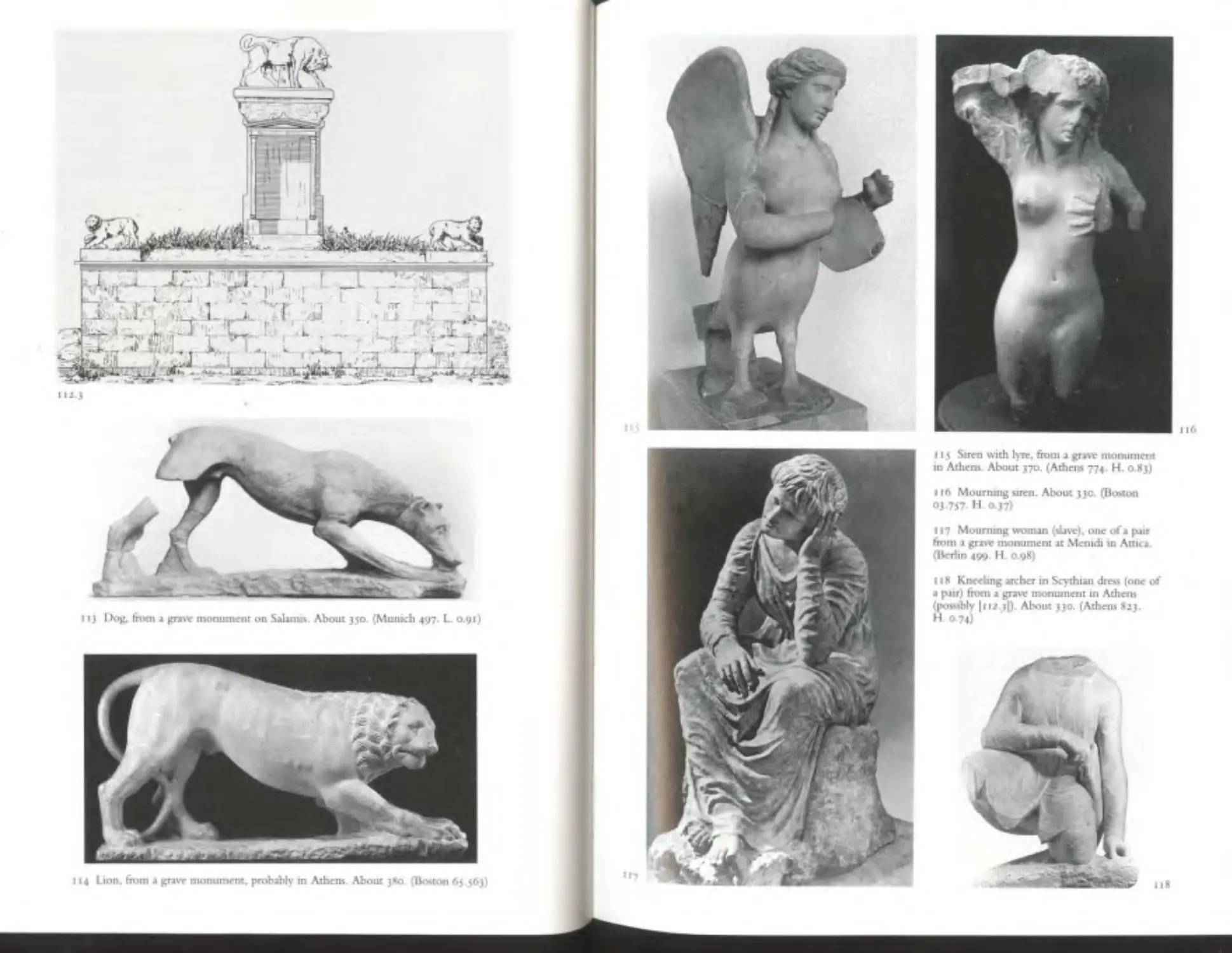

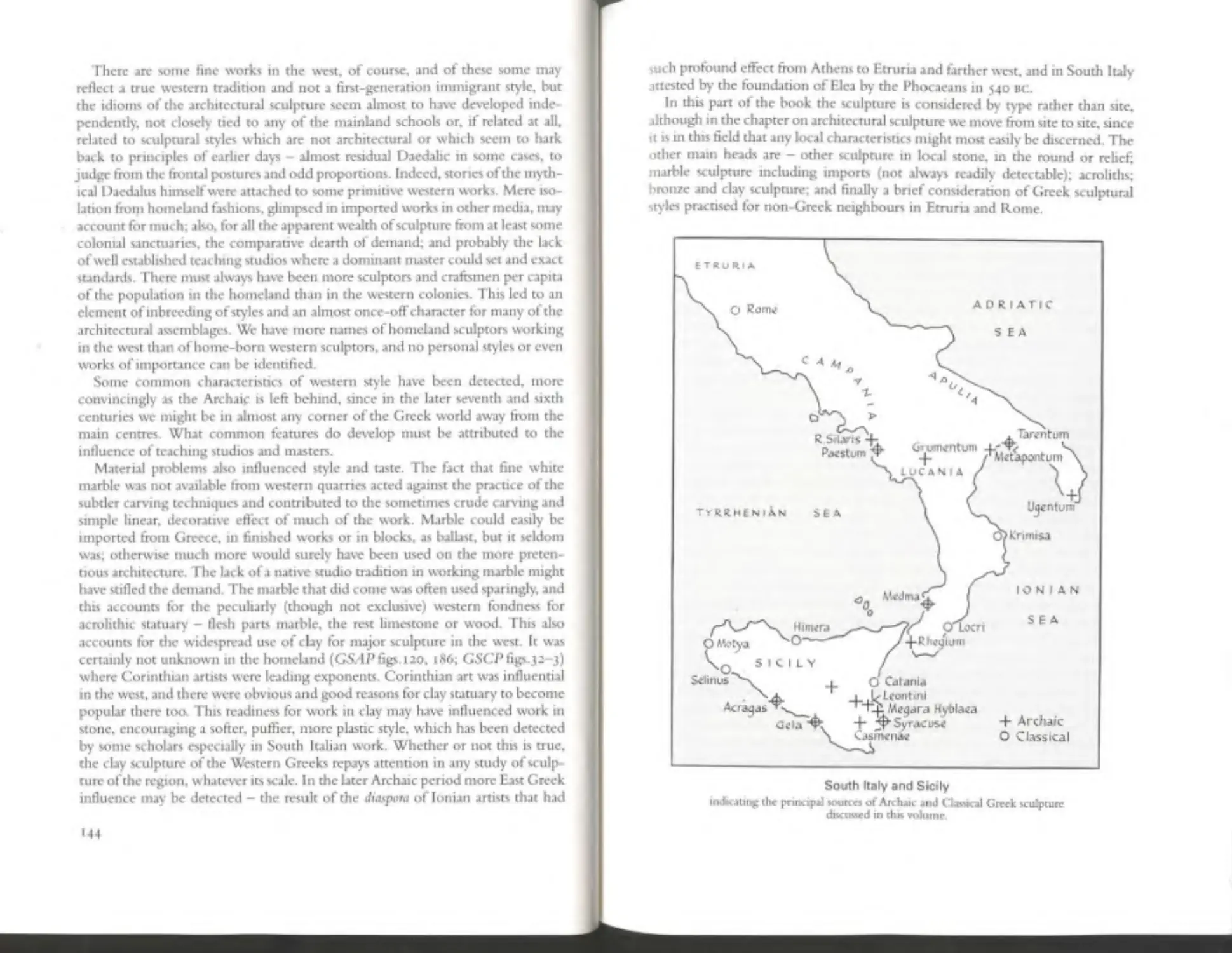

So111l1 Italy a11d Sicily {p. 145)

222

237

238

Preface

This volume is a se quel to the two on the ArchaiC and Class1cal periods o f Greek

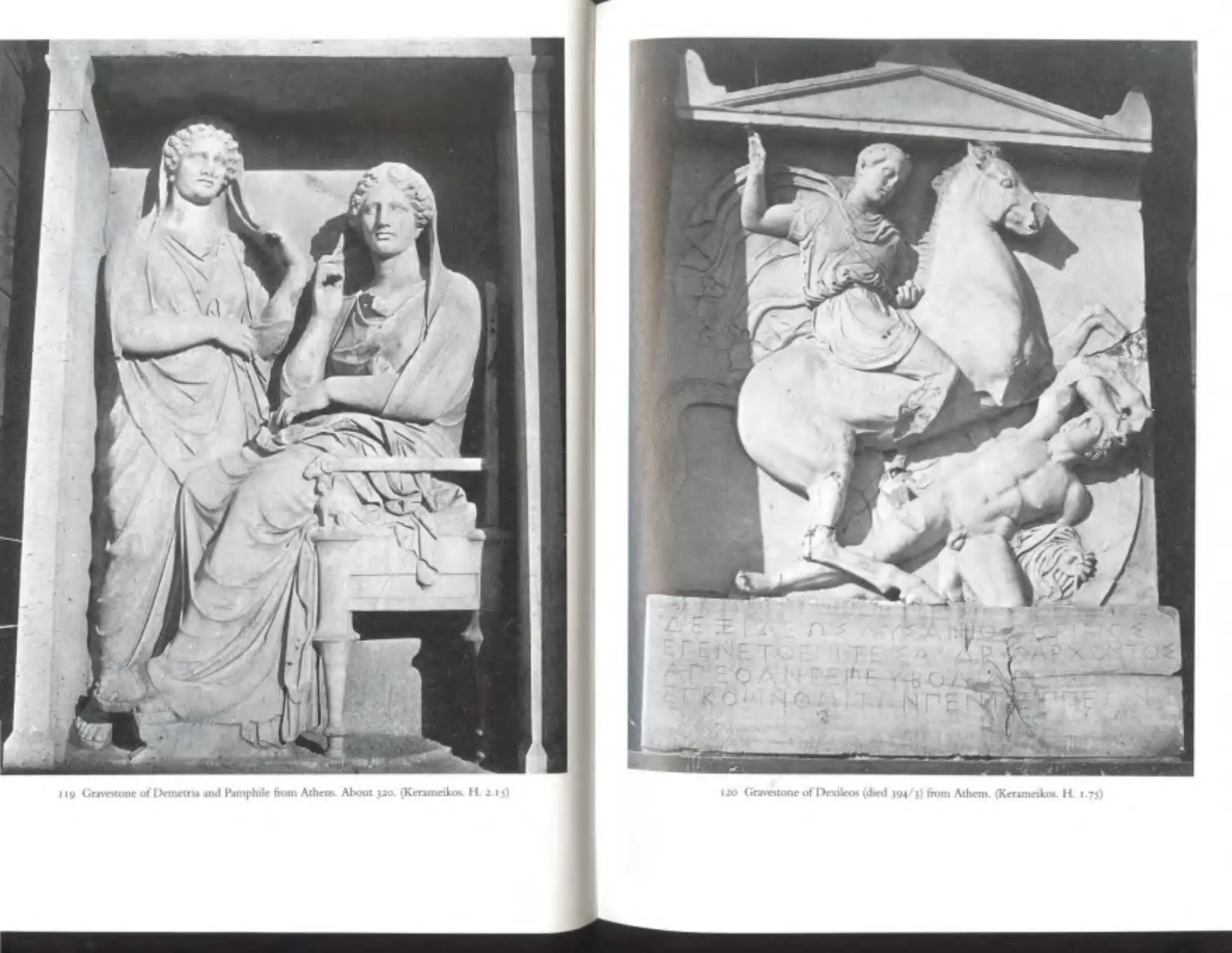

sculpture wh1c h have already appeared m this ser ies {1978, 1985). Its narrative

ends more or less where R . R. . R. . Smith's Hellenis tic Swlpture (1991), which is

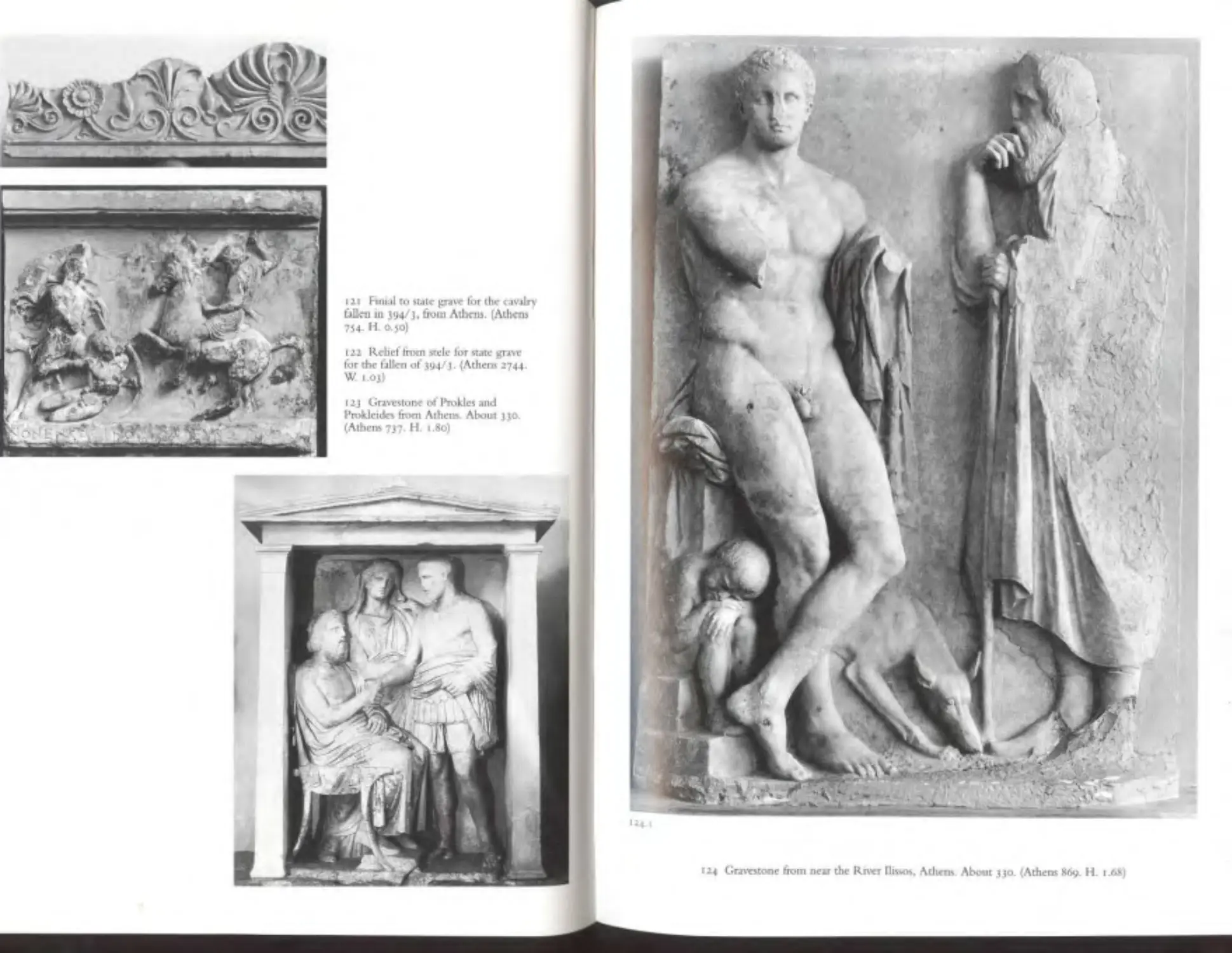

des1gned along similar lines, beg1ns, w1th som e ove rlapping. But it also includes

conSideration oft he Greeks' scu lptural record in thei r western colonies, in South

ltalv and Sicily, and work executed for the ir eastern neighbours in Anatolia and

els;where in the near east, and in these Parts (If and IIf} th e narrative begins in

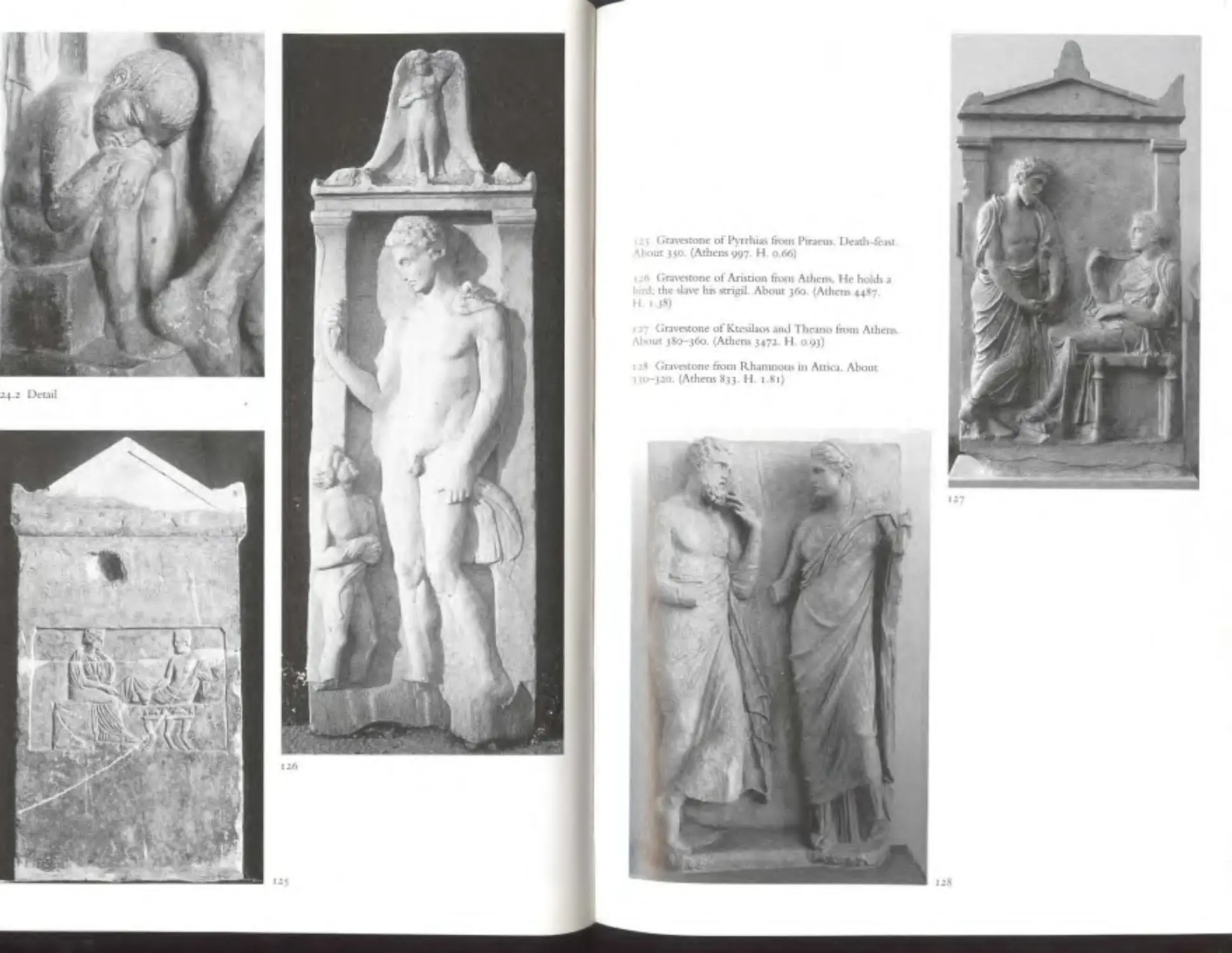

the Archaic period. So the first Part represents a period o f transition - indeed in

some classes o f sculpture it may seem like marking tim e. T h ese are yea rs in which

the Clamcal revolution of the fifth century was se ttlin g down with modest

e~l'eriment, bu t also with so m e significant novel ty that presaged th e Helleni stic

styles to come. In it we see the beginnmg of the b reakd own of C lassical stan-

dards, but also the inception ofnew modes o f e"l'rcssion - the female nu de, true

portraiture, passionate features and poses. These also depart fro m C lassical prac-

nce<-, though they are rooted in them, and they introduce much that was to be

oHhtmg significa nce m th e class1ca l sculptu ra l tradition of the west.

In thrs period ofless t han a centu ry t he 1mpcnal ambin ons ofa newly defeated

Athens gave place to a vanety of Internal alliances m Greece. These local pre-

occupanons were more and more overshadowed by th e now more benign inter-

ference of Persia, and by a sh ift of power and wealth to north Greece and

Maccdorua, whence Ph1lip If and h is son Alexander the Great were to laun ch

their successful confrontati on with the Persian Emp1re. We are moving from a

period m wh1ch artists and cra ftsm en were servrng the monumental aspirations

of relatively small though sometimes wealthy states, to one in whi ch the wealth

of mdividuals and dynasties \vaS becoming a more effecnve source o f patronage,

and in wh1ch •ervice for the n o n-Creek could prove espec ially attractive. But

overall, the art o f fourth-cenn1ry Greece had as much in common with its High

Classical past as with its Helle nistic future.

The study ofGreek sculpture is a ve ry old o n e and methods h ave chan ged but

little. It depen ds, as it must, on close inspection and experien ce. The role ofcon-

no"seurship and attributi on to names o f scu lp tOrs and schools remains impor-

tant . but m the face ofwidespread disagreement over acceptable results it seems

tlllle tor a more closely archa colog1ca l app roac h; for example, a more rigorous

7

assessment oftechnique which can prove offundamental importance in explain-

mg intentions and changes of style as well as date. And JUSt as the traditional

methods ofstudying Greek vases have been - not overturned- but, for the dis-

cerning, e nhanced by new approaches and new focuses of mterest over the last

generation, so too it may be time to reconsider approaches to sculpture. T h is is

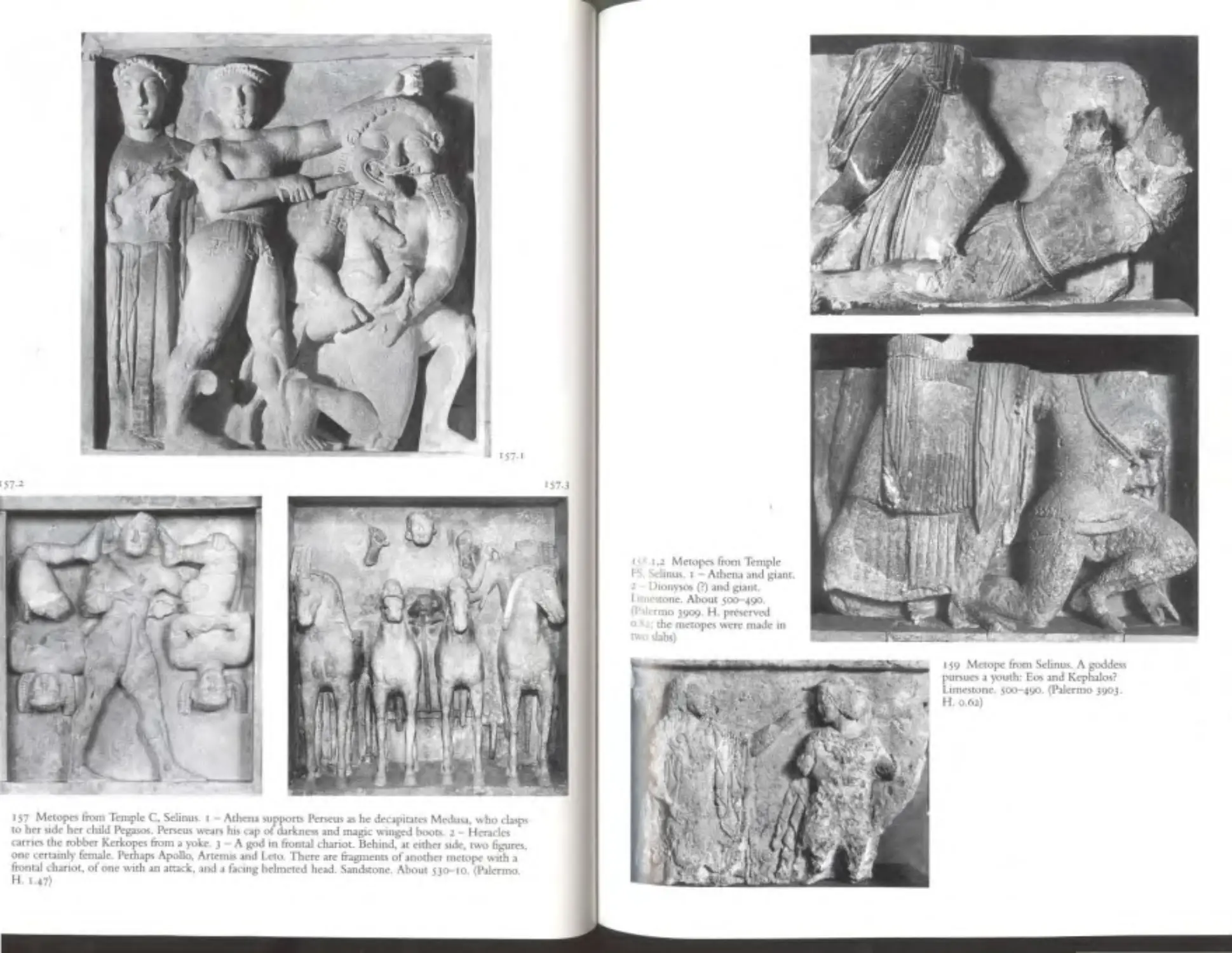

beginning, mainly in terms ofstudy of its fu nction as social display or for poli t-

ICal and rehg10us propagan da. There is not much room to write about such

m atters here, in a h andbook devoted to th e primary evidence, but they will find

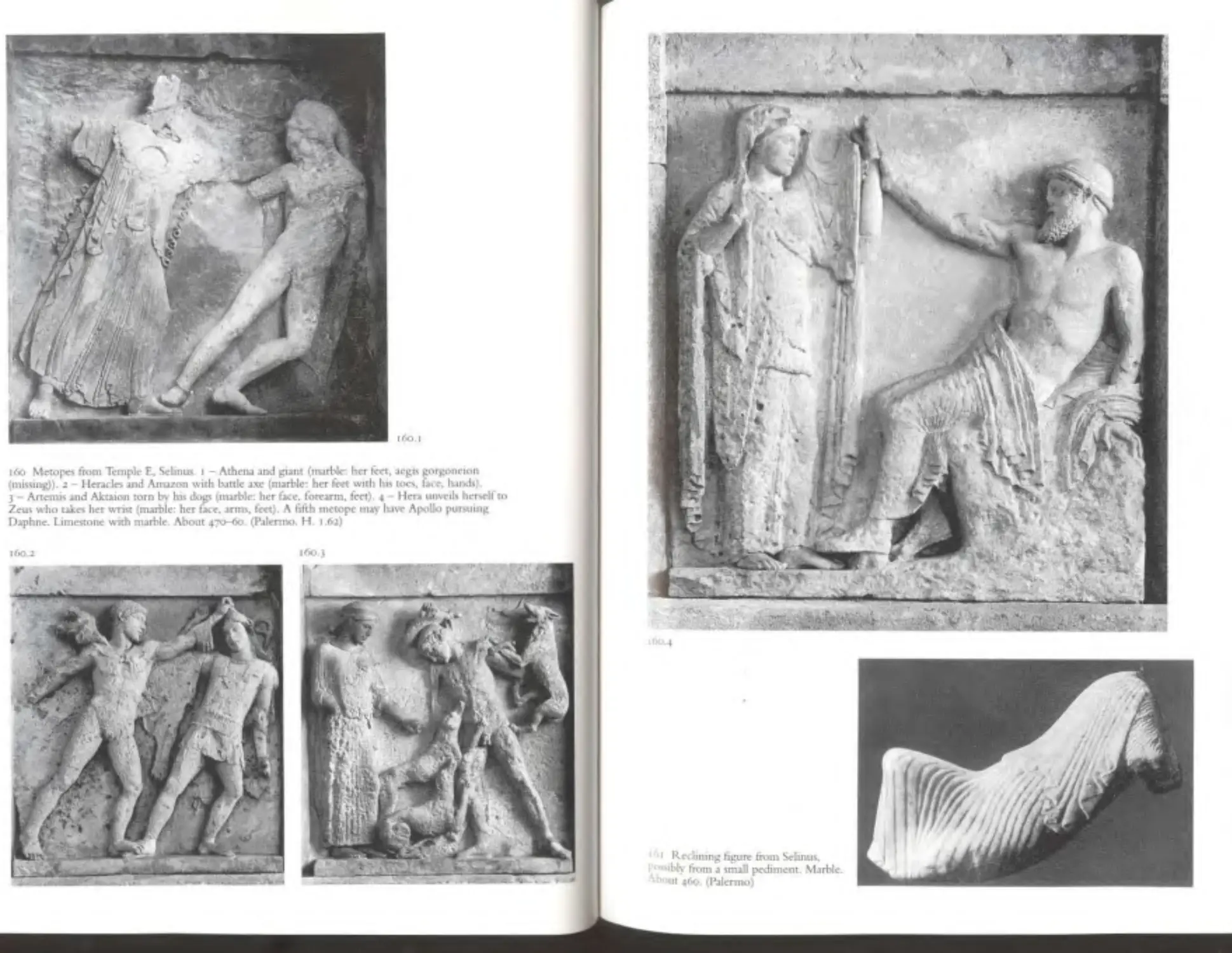

their plac~. More impor tantly, I would invite the reader tO refl ect on why Greek

scu!pture IS Important, and not merely in terms ofwhat it inspired in later cen-

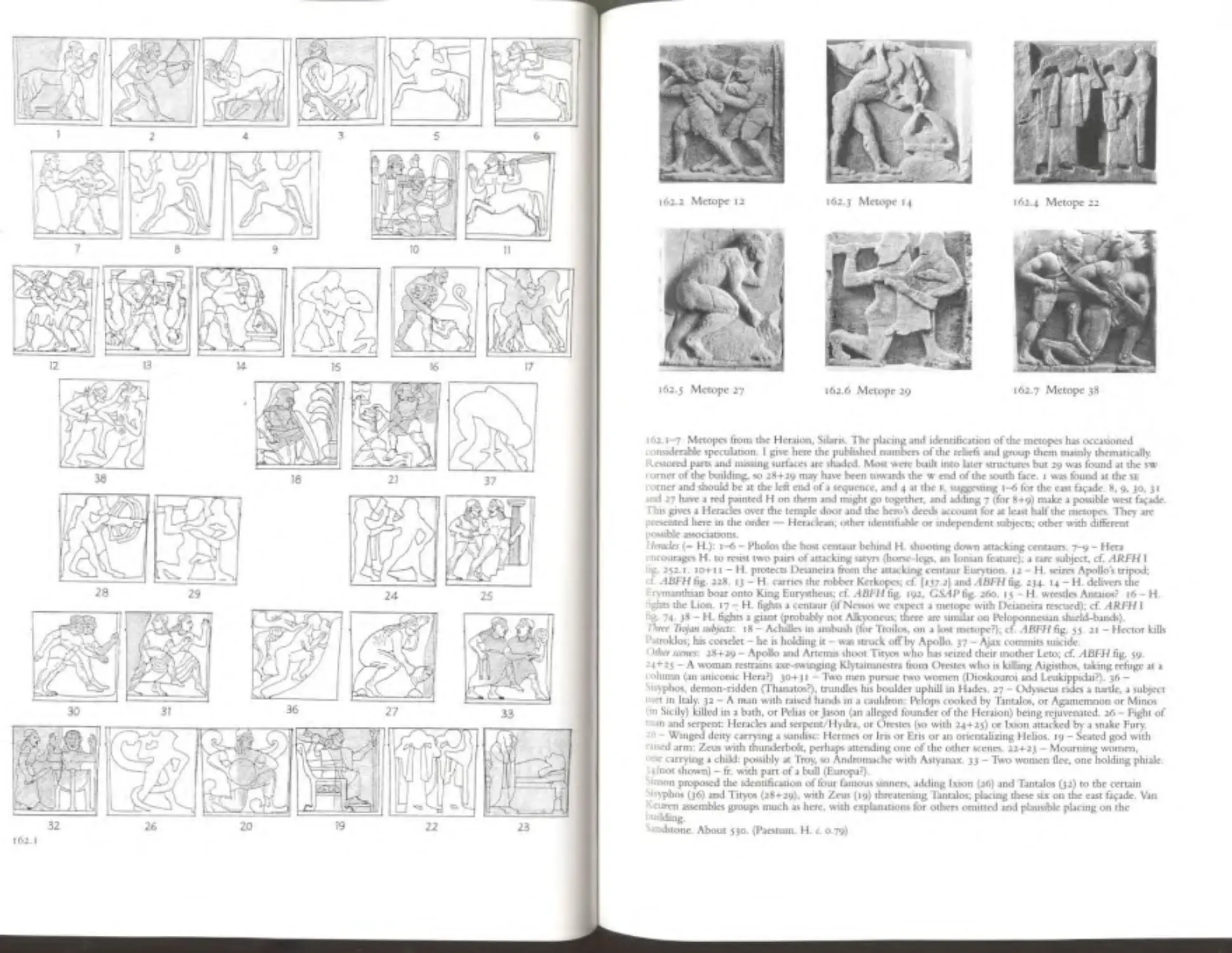

tuncs. lt has often been remarked that the Greeks seem ed to live in a world of

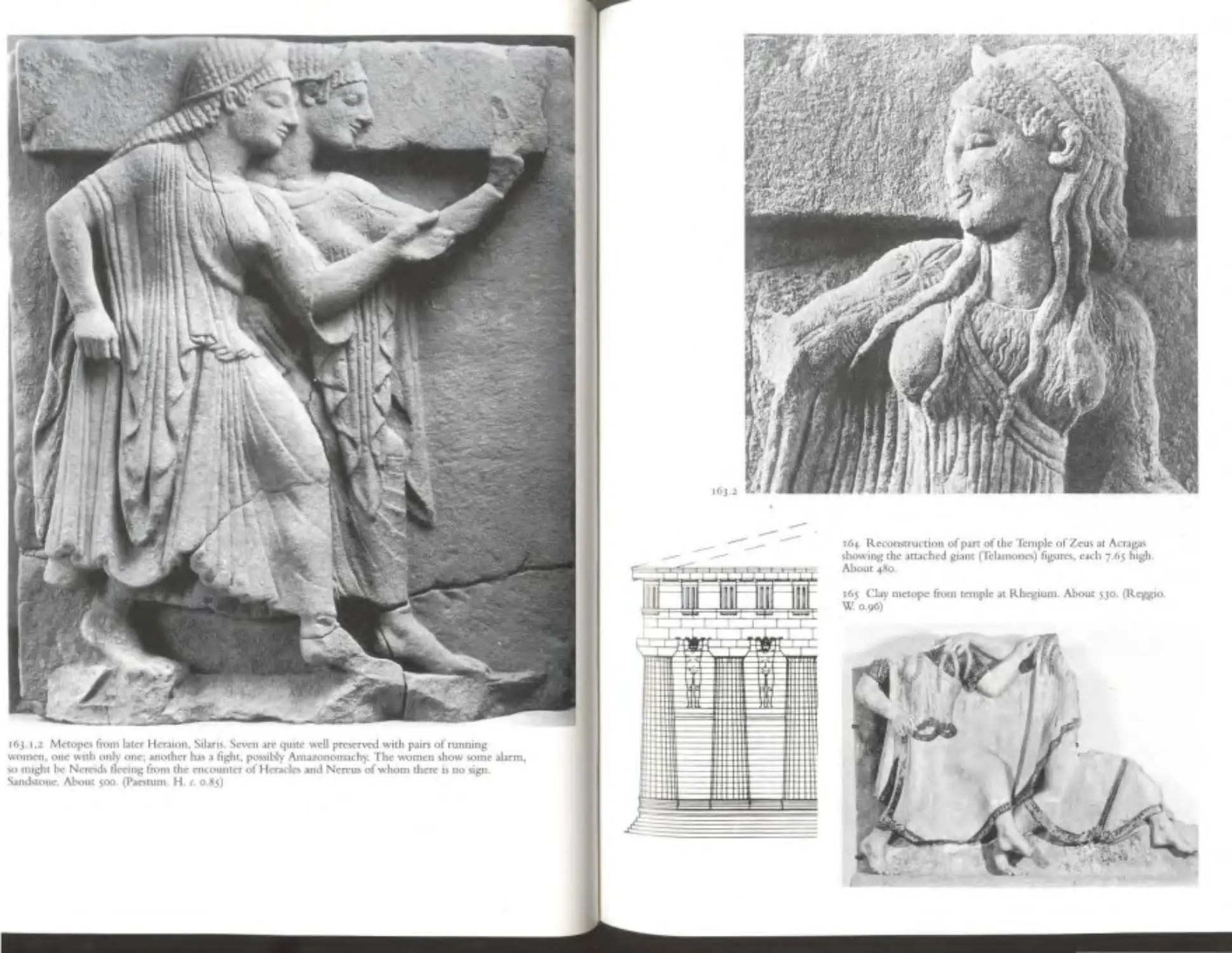

images. So.did other cultures, but there the ordinary citizen \vas exposed to such

Images, painted or sculptured, mainly in the exceptional circumstances ofcourt

or r~hgious life. The 'small-town' mentality ofthe Greeks and a roughly demo-

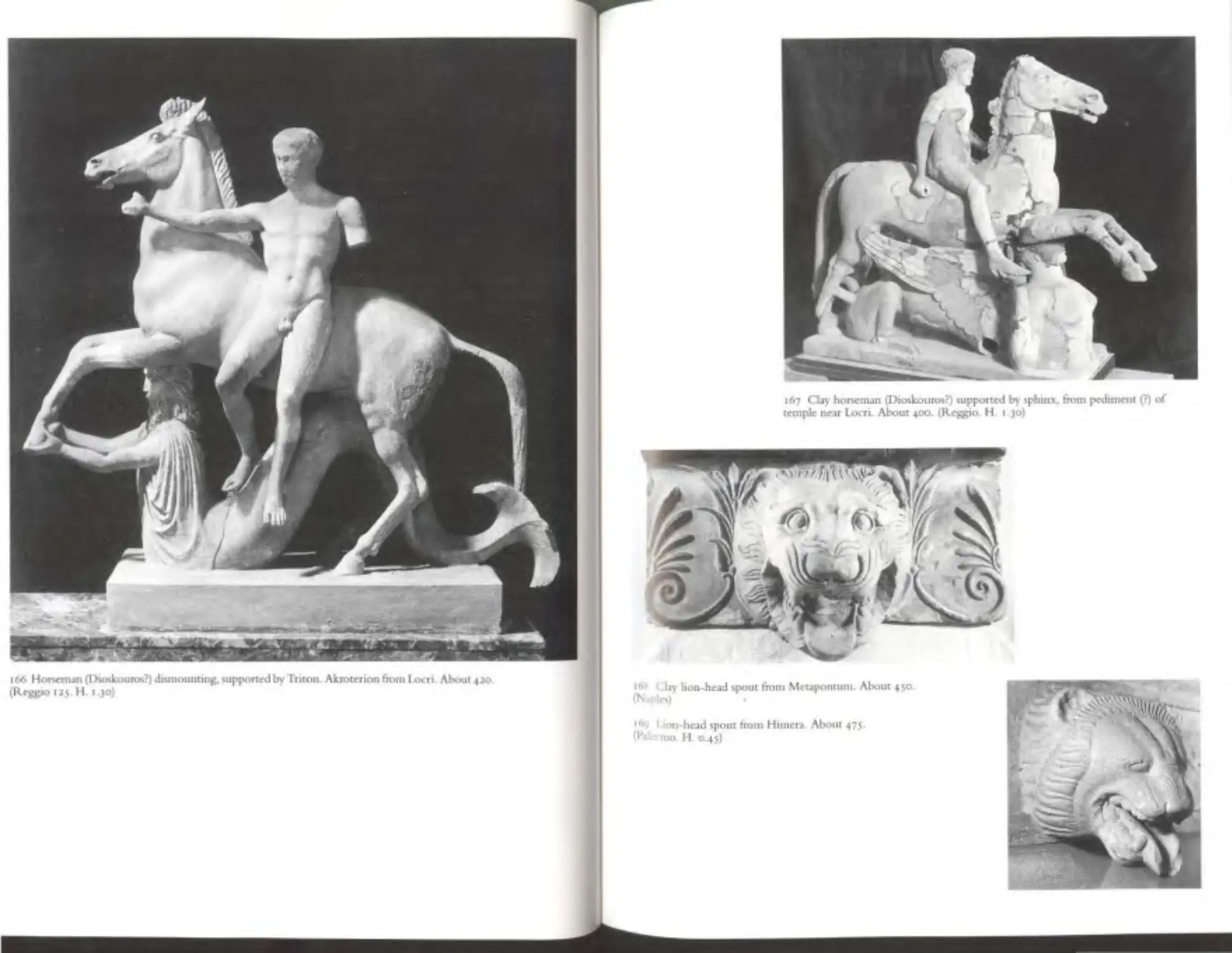

cra n e \vay oflife, at least m Athens (our major source), m eant that exposure was

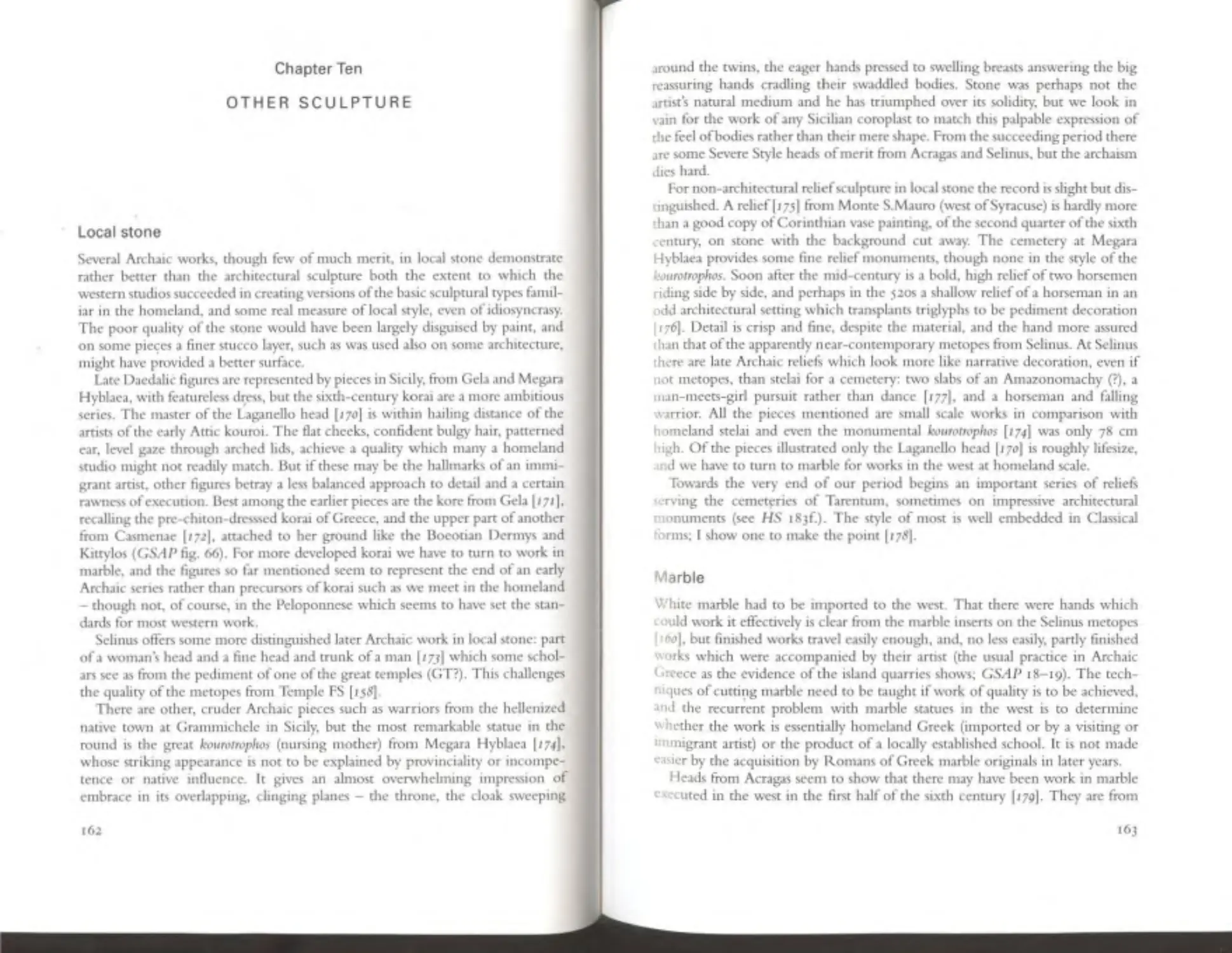

far m ore general, at all levels o f society, even the servile. Here and there I refl ect

o~ what the Greeks migh t have made ofthe monuments, ofthe sculptural show-

pieces 111 m ar ket- places, sanctu aries and cemet eries. It is a way ofcoming closer

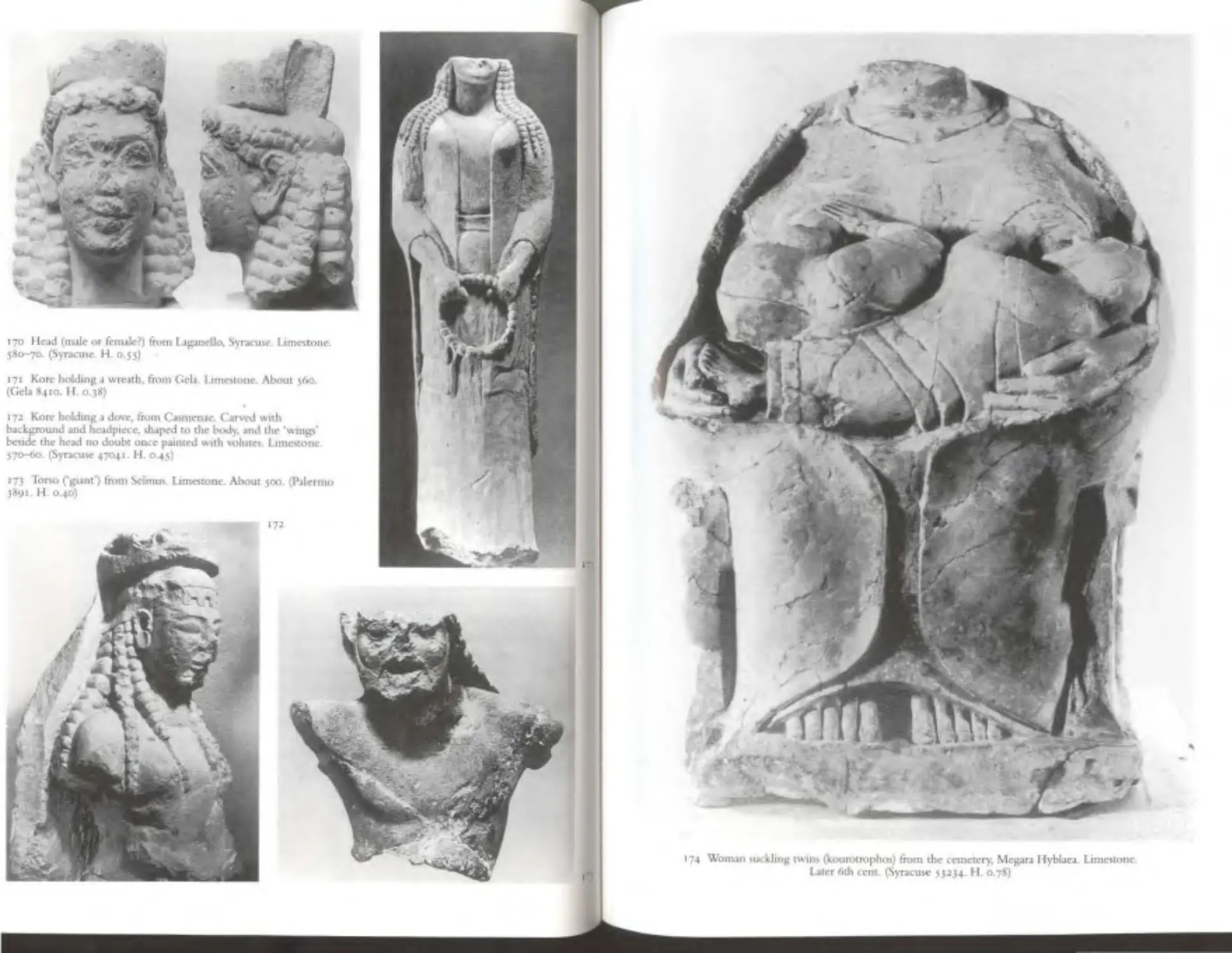

to u nderstandm g the expectatio n s of the public an d intentions of the artists, and

possibly an easier and no less profitable one than that offered by the more rari-

fied atmosphere oftheir literature. We do not see what they saw exactly, but we

can learn to Imagme what they saw in considerable detail and with considerable

accuracy. The physical e nvironment created by any society tells much about that

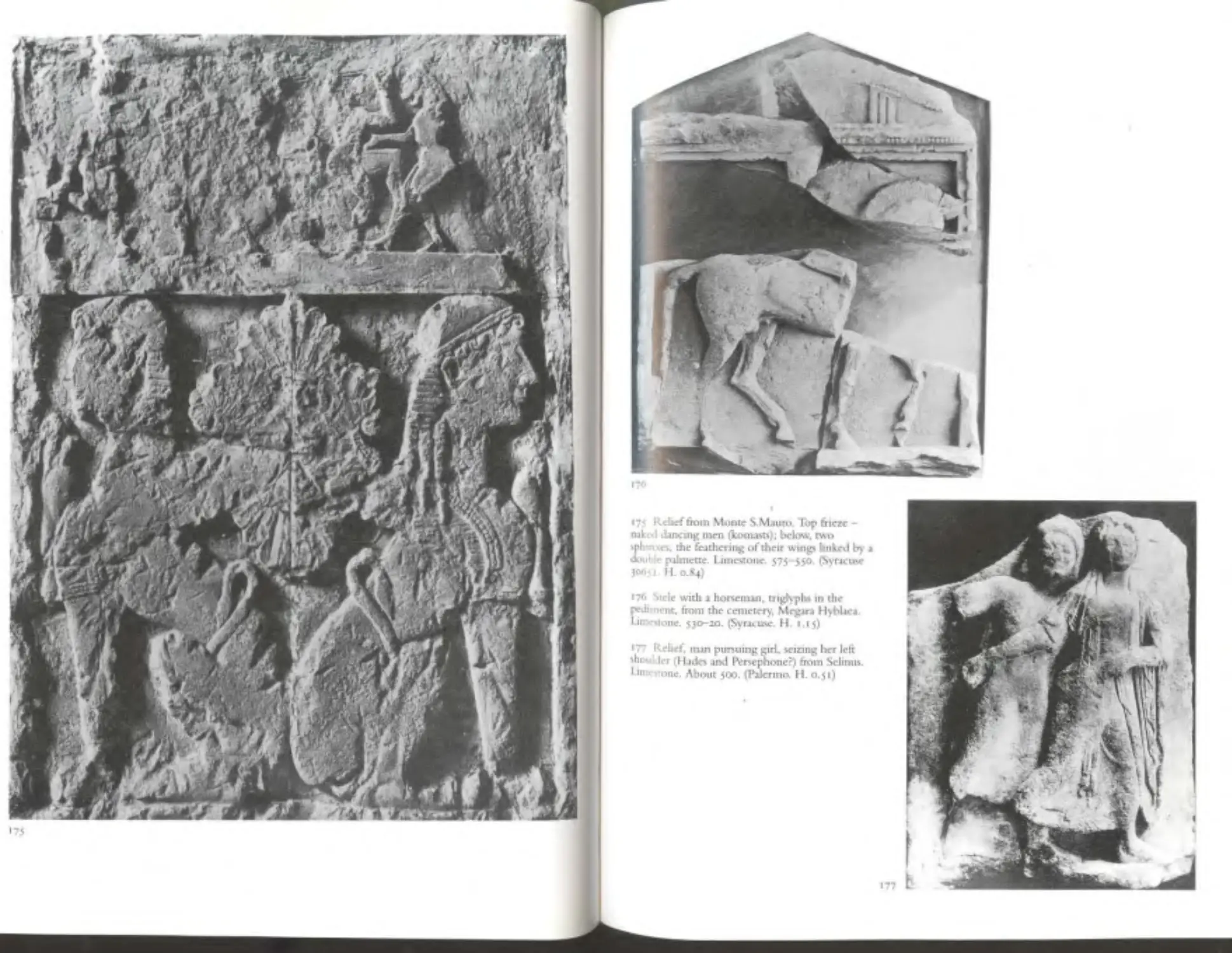

society's character. A closer look at Greek politics and social behaviour might

lead us to suspect that we have been admiring them for the wrong reasons; but

we have a good chance ofsh aring their appreciation and even u nderstanding of

the1~ physical environment, dominated as it was by th e work of gener ations of

architects and artists . Th1s work was more obviously ap paren t and less distant

from t he trappings ofordinary li fe than such monuments are today. This should

be o n e of the rewards of th e subject. But it starts necessarily in study of tech-

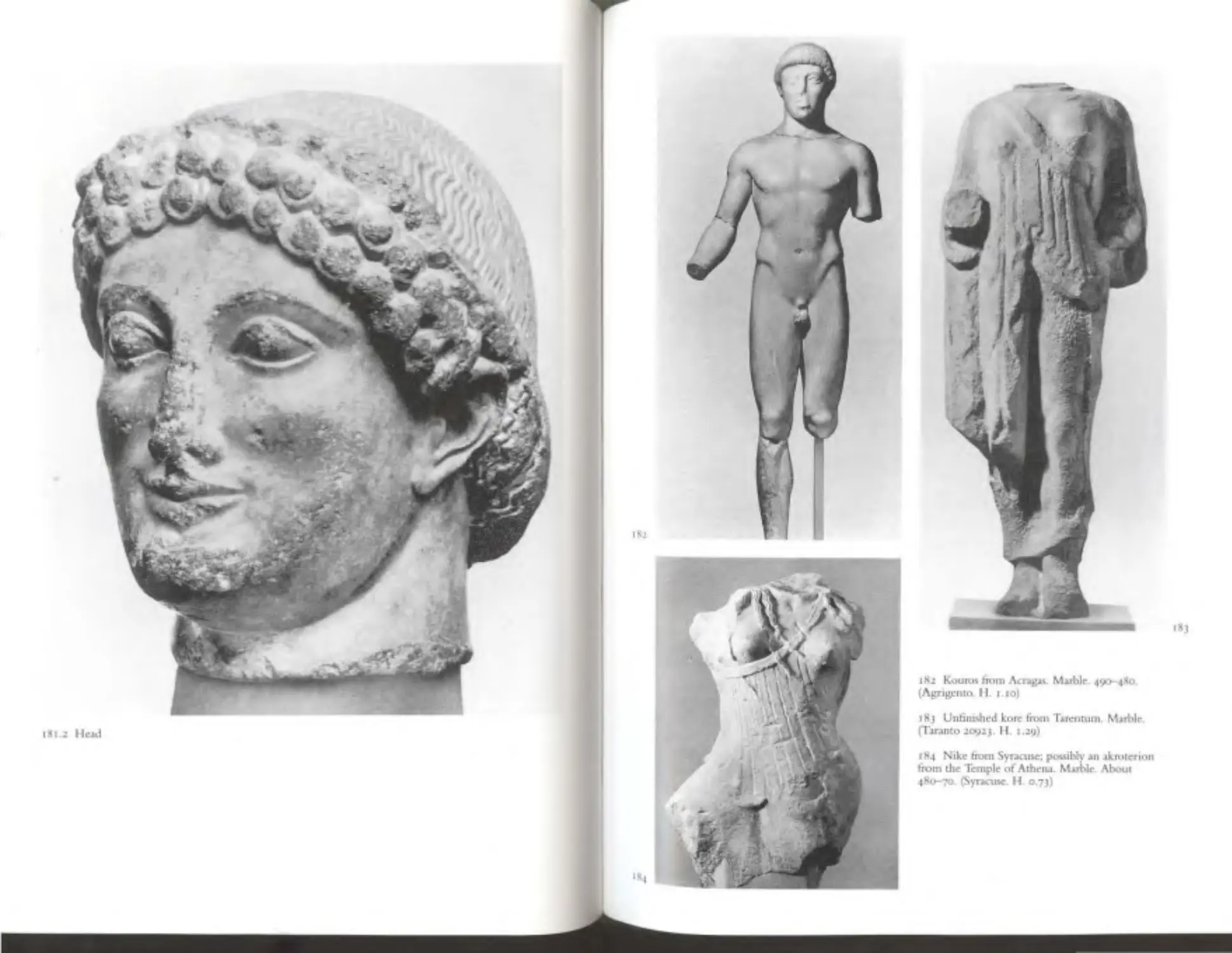

mquc, pose, dress , composition, subject matter, function, sources, dating, and

calls for the exercise of traditional skills as well as an imaginative empathy ,vith

the visual experience of the past.

The scheme of this volume deviates little from the gene ral pattern of its pre-

decessors. The mam chapters present and describe the record by principal types,

and bymdiv1dual sculptors where possible, concentrating on the surviving phys-

Ical evidence. Broader considerations of th e development of style, technique,

patronage, funcnon, and the social role ofsculpture and sculptor s, are assembled

111 the first chapter, an d h ere there is necessa r ily an elemen t ofrefl ection 011 what

had gone before. In Parts ll an d llJ the progress is mainly geographical, attem pt-

m g to uncover regional preferences in the colonial world, and th e effect ofn on-

Creek interests on artists commissioned outside it. The final chapter refl ects on

how we have come by, and used, our coll ections of classical sculpture; the

8

·sponses to the ancient and to what we term the antique. The maps

clifferent reunary indication of th e main sources of Archaic and C lassical sc ulp-

g1ve a ,un

om1dered in these handbooks.

cure cb fore , 1 have tried to supply student and general reader with enough pie-

Mc

·

fh·d.

d

,.

111 an idea ofboth style and subjects. Some o t e p1eces 1scusse are

rures to g

·

·

b

·

Iddb

f d . · later than the declared 1ntennon ofthe volume ut are me u e ecause

oa.lt<

.

ft .d

I fleet 011 earlier work and are nor to be found m HS yet are o en c1te .

ney re

.

.

Where expedient 1 have used ph otos of casts smcc they arc somenmes m~re

tr: t , 111 demonstratin g form, and the surface condmon of an ongmal1s VIr-

m~~

.

.

.

.

.

all

.

1,·vc r as it was m annqmty. 1 have not shirked photos w1th black back-

tuY

f:·blC

·

·

rout' ),, though these are gen erally un ashiona e. . ontours were Important m

gl ·c

atuary much of which \vas displayed agamst a wall or m rebef on a

c asst

•

.

.

dark-v• ,ted ground. I! 1s noticeable that where statues were mtended for display

n s bright sky th e outlm es ca n be vaguer, even ragged. The matenal of

agaiec es hown is always m arbl e unless otherwise stated; all dates are BC and

P

1

.

d

d.

d

measu.vnents in metres. Marion Cox has created o r cop1c m any rawmgs, an

1am, • often before, much in her debt. I am grateful to many generous sources

for illustration and have drawn o n th e Oxford Cast Gallery Archives. A n d I am

deeply inde bted to Olga Palagia for advice and correction, but claim credit or

blame or all idiosyncrasies and errors myself.

9

PA RT I. LATE CLASSICAL SCULPTURE

Chapter One

INTRODUCTION

Style and Technique

The Clao;sic al revoluuon in the am of the fifth century led sculptors to attempt

to reconcile their theones ofproportion, which expressed the ideal norm for the

hunvn body, with total realism. T h ey wrote books abou t proportions (symme-

tria commensurability of parrs) and we attempt to recapture them , with sca nt

succe", through observation an d measurement of copies of their works, made

centuries later. Their attempt to reconcile m athem atical uniformity o f p ropor -

tio n with life was more successful than th e product of earlier and non-Creek

m easurers and plotters of the human figure had ever been . The rea lis m is appar-

ent to us o nly in their command of anatomical detail an d pose, and they seem

to have been as near successfu l as was required to produce a completely lifelike

figu re. fo r all that some anatomical detail may have been made more regular than

nature eve r intended or achieved. Wh1le the succeeding Hellenistic period is in

some respectS more lively in irs am, it is to no appreciable degree more lifelike,

since m artisrs exploited the1r skill s at counterfeiting life for purposes which led

to the rea tion ofvery srnlung though not so strictly correct images. This applied

even t'J figures m repose.

Mo jern observers and art histonam are ready to adnm all this; they acknowl-

edge the attempt and the success; and they sometimes even wonder why the

Greeks bothered. But they look ma1nly at the sculptures in terms of mass and

for m, not of surface. We tend to resist adnumng that Classical realism also

embraced the way the figures were fimshcd because none has survived in its pris-

tme se1te, and our appreciation of the true Class1cal has been maimed by the

R ena1ssa nce 's insi stence on the piam wh1tc forms in which classical sc ulpture

bee me known . There is every reason to thmk that a virtual trompe l'oeil effect

was 1med at for lifesizc figures, the heroic being only centimetres larger

(compare the relative thou gh redu ced proportions o f men vis-a -vis h eroes on the

Parthenon Fneze; GSCP 108 , understated, fig. 96 .16). It was this absolute

"'""' is, a counterfeit ofnature, that upset th e fourth-century phi losoph er Pla to,

who Jbscrved how artistS made optical corrcctiom for different viewpoin tS, and

saw that such work co uld both deceive and ye t fail to represent the true, ideal

form ofobjecrs and men . Such an effect was surel y achieved w ith m arble figures

and •• is unbkcly that bronzes were marke(Uy different. For these we have only

11

the evidence of surviving inlays for some patterning on dress, but we sho uld

adnut th e probabili ty of extensive painting too. The pale brassy flesh was lifelike

m 1ts ongmal condmon and could be kept bright, while gilding offlesh, which

was also practised, need not have been un-lifelike with colour-enhancement of

the metal. lt was alleged that the fourth-century sculptor Silanion used a silve red

bronze to express the wasting flesh on the face of a dying Jocasta, and there is

reference m a nctent authors to the use of different alloys for colour effect. The

Greeks were not wedded to the idea of expressing the character of their mater-

ial in their art and architecture, and could even go to som e pains to obscure it,

even 1f th~s meant some .d•sgmse ofthe va lue ofthe materials used. On th e ch ry-

selephantme figures whtch served as cult statues th e tinted ivory \vaS lifelike and

the gold raJment s•mpl y sumptuous. Only their colossal size was quite unreal,

m tended to evoke a different aesthetic and psyc hological response. We may judge

from the colossal figures. of other cu ltures (Egypt, India, the Statue of Liberty)

how madequately coloss • reproduce the essence oflifesize works execu ted in the

same style, and es pecia ll y where that style is realistic.

Chryselephaotir:e cu lt sta tues were still being made in the fourth century, and

Phthp ofM acedon s famtly group at Olymp•a was ofgold and ivory, but th e prac-

ti ce for colossal fi~1res almost dies o ut although gilding of bronze was probably

very common, g tvmg the flesh parts a dusky glow, not unlike the bas ic bronze

(brassy, we might call it) and making the dress cloth-of-gold. For the bronze and

marble works ':"e hear of well-known collaborating painters (e.g., Nikias with

Praxltel es), whtle Euphranor was both a sc ulptor and a major painter. More than

once we percetve m sculptural g roups and reliefS compositions that seem to have

been derived from painting. Trompe /'oei/ realism was an achievement ofpainters

also from the end of the fifth century; sc ulptors could outdo them with images

at life stze and m three dimensions, and we should ass ume that this \ V3S

commonly thetr intention.

Anatomical accuracy had been achieved in the fifth cenrury, though the sc ulp-

tortended to make bodtes more absolutely symmetrical than they ever are in life.

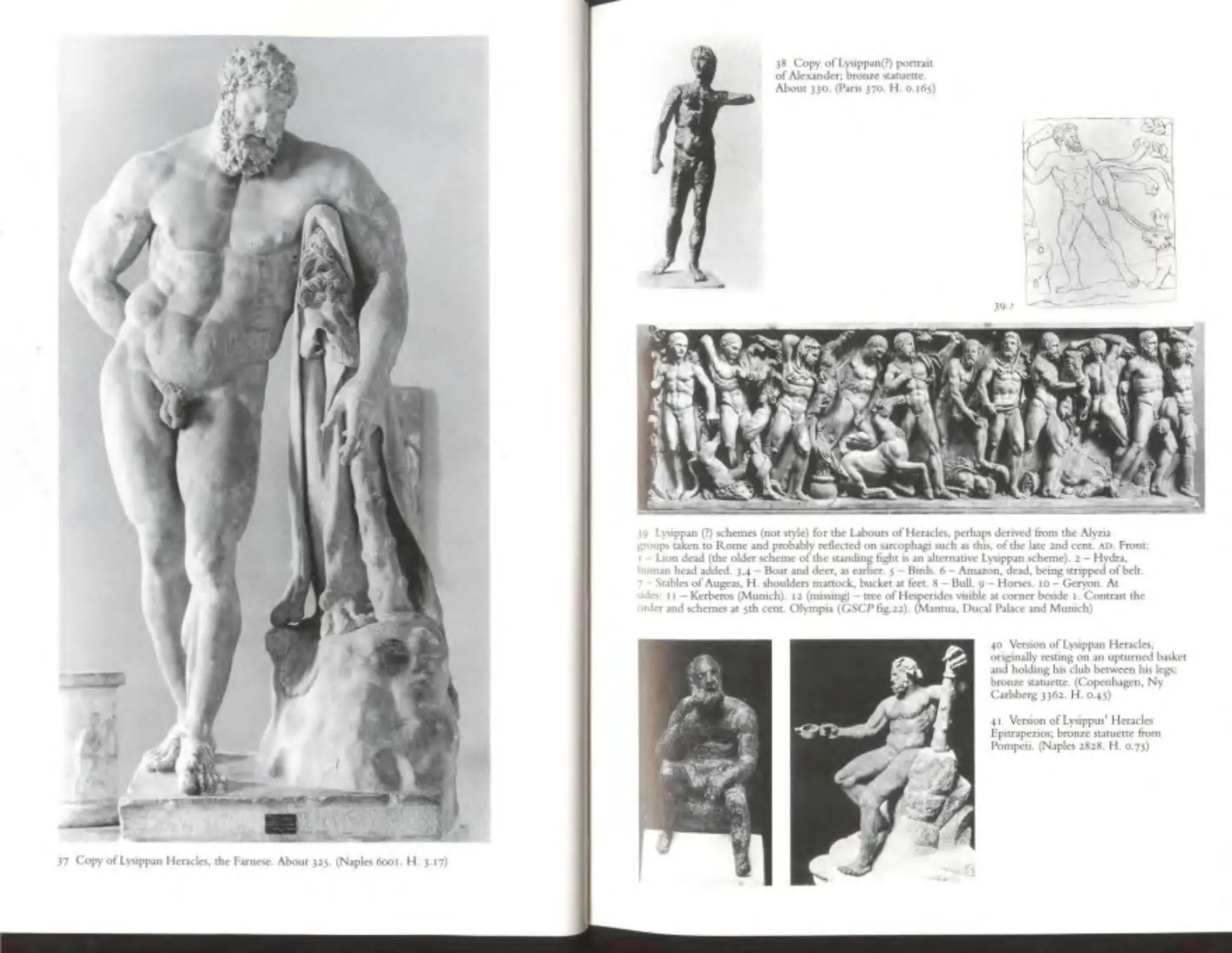

Th1s.was a legacy of~rchaic patter~, no doubt, as well as a conscious attempt to

tdealtze. The modelhng. techruque m clay that lay behind all major Greek sc ulp-

tural work from th•s nme on, whatever the eventual medium - ca rving in

marbl e, casnng m bronze, assemblage in ivory and metal sheet - abetted this

preCISe expressiO n of the human form (on basic techniques, GSCP 10ff.). 'The

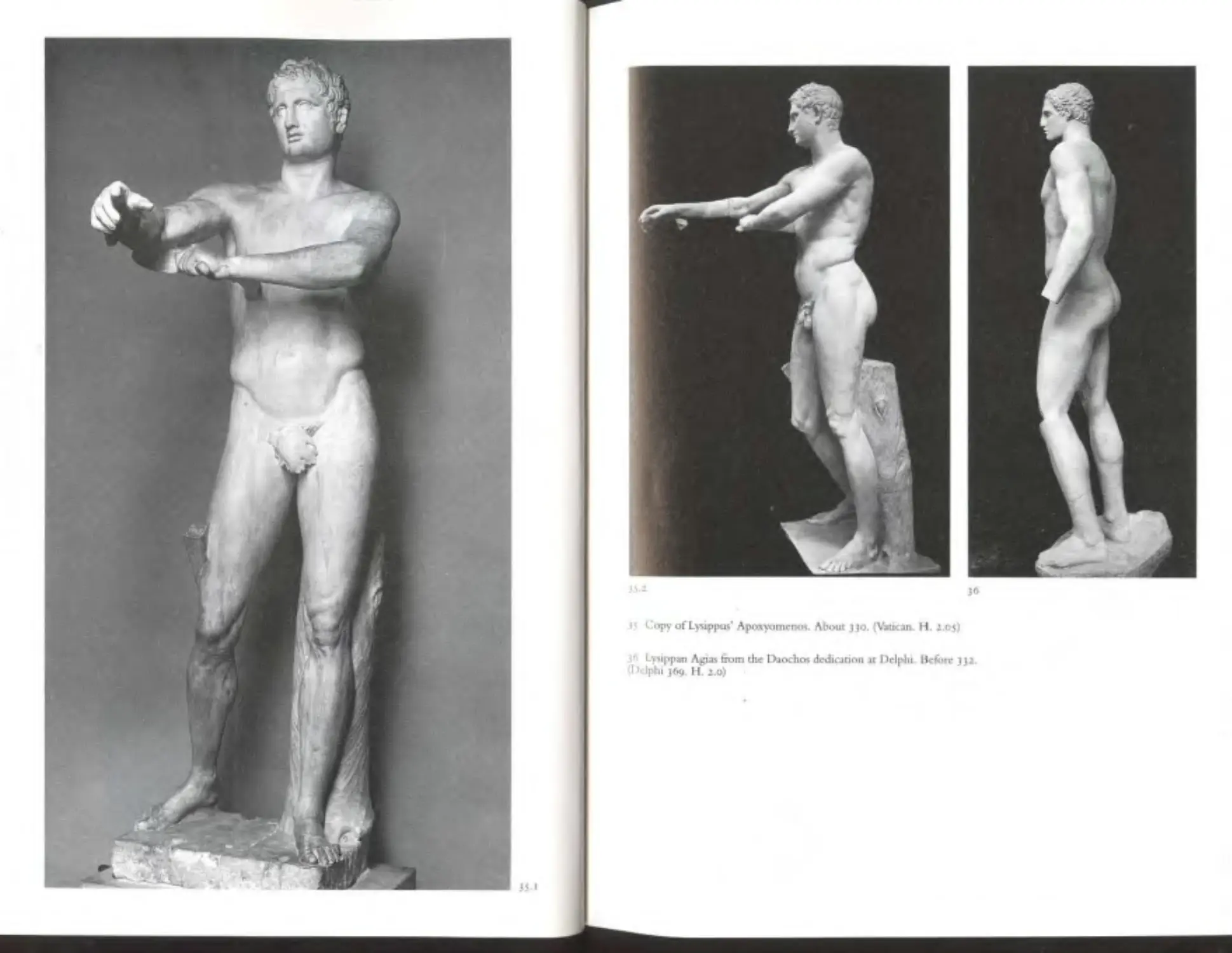

':ork IS hardest', sa id Polyclitus, 'when the clay is on th e nail.' The main excep-

n o ns to utte r reah sm a re m fearures, where those of women remain very mask-

like, and where eventuallyth ~re. may be either a slightly impressionistic so ftening

of forms.' or an cx press •o msnc exaggeration of them, both presaging the

HeU emstJ c. Adept casnng was an essential element in the processes oftranslation

from clay model to finished sta tue, and it was inevitable that there would be

expenments m casnng from life. It was probably commoner than we c redit, sin ce

we h ave o nl y the record of Lysippus' brother Lysistratos, the first (according to

12

b •) to m ould a likeness in plaster from a f.1 ce and to correct (or repair) a cast

p n~ use o f life-moulds. lt is likely enough that dress too could have been sup-

b~:d:n the clay or plaster model by appli~at~on ofplaster- or day- soaked cloth.

~he technique is well d~cumented ·~ R.odm s workshop. He suffered from accu-

s th at h is /'Age d'a~ram was bastcally cast fro m life (surmoulage). We have no

o;ao onn to believe that such a practice would have been discredited in antiquity;

reaso

.

.

uitt: the reverse. (In modern sculptors 1t can be counted a v1rtue!) When we

q der the story of how Praxiteles made a naked and a clothed vers1o n of hts

cons1

.

.

.

A hroditc (for Cnidus and Cos respecuvely) we can see how read1ly t hat nught

h:Ve been achieved from a single prototype, though t he limbs would have

reqUired remodelling for a different pose. lt is only recently that schola rs are

begnu1111 g to admit the possibility ofsuch techniques, yet they are almost manda-

tory such resu lts are to be achieved, especially where complete accuracy m

anatomy and posture we re imended. Sculptors find it inescapable for works of

classtcal realism.

1t 15 unlikely that such di rect work from life was long prac tised, at least to judge

fro m ·csults. This is also, inevi tabl y, the period in w hi ch t he artist's model begins

to be an important clement in art hi story, also shortlived. Ph rync is sa id to have

modelled fo r both her lover Praxiteles and the paimer Apelles. T he forme r 's

Ap hmdite was sa id to have become th e object of indecent assa ult, it was so life-

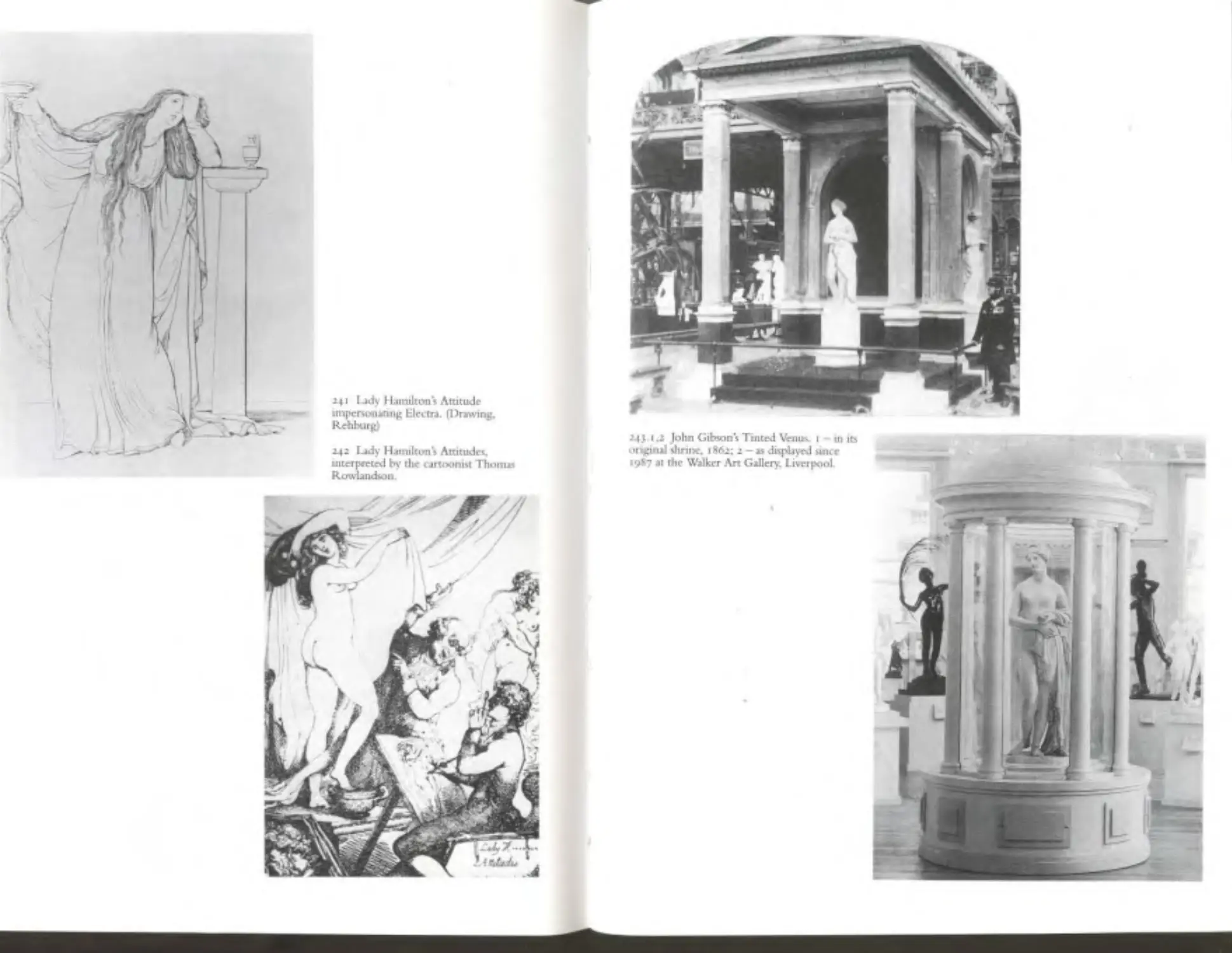

lik e. rhe best idea we can get of it is 111 John Gibson 's Ti11ted Venus in Liverpool's

Walker Art Gallery, but there she is an etherialised Victorian [Z4J].

T l e role of some of t he sc ulptural media has been remarked already. Wood

seems not to have been important for major works after t he Archaic period,

thou 11 it was surel y much used for cheaper and ornamental work , as was clay.

For major sculpture, once a clay model had been made by the master sculptor

its tramlation into bronze requi red extreme sk ill and relatively expensive mate-

ri al but not too much time and labour; if it was eo be translated into marble the

matenal was nor expensive but it \vaS very dtfficult and could be very expensive

to deliver to the studio fro m th e quarry, and needed many mason-hours ofwork.

O ne ma n-year for a lifesize figure, 1t IS alleged , but labour, even of masons, was

cheap. In the fifth century marble had been much used for archi tectural sculp-

ture 1nd reliefS, though not •gnored for individual srames or groups. The differ -

enc( was probably large ly a matter of cost and practicality. Praxiteles is the first

maJor na m e to whom several marble works arc ascribed where we may believe

that ~e motivation was a deliberate aesthetic exploitation of the material ; that

is, ••.we assume that for hi s female nudes, another of his innovations, he left the

flesh parts unpainted or at best so tinted as to make the m ost ofthe flesh-like

qu;,litJe s of the stone. The encaustic technique of painting, applying the colou r

in hot wax to a polished surface, does m u ch to preserve the translucent quality

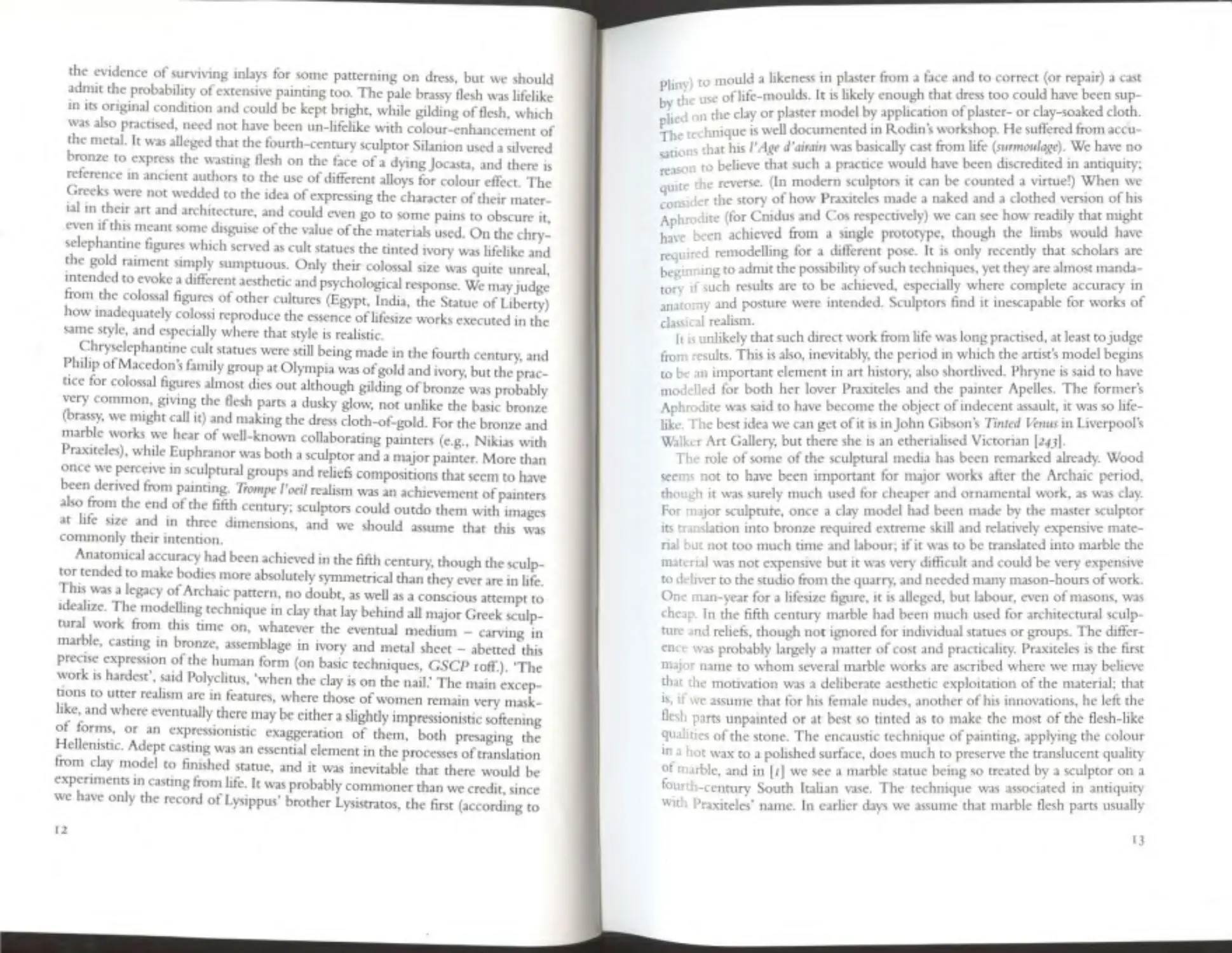

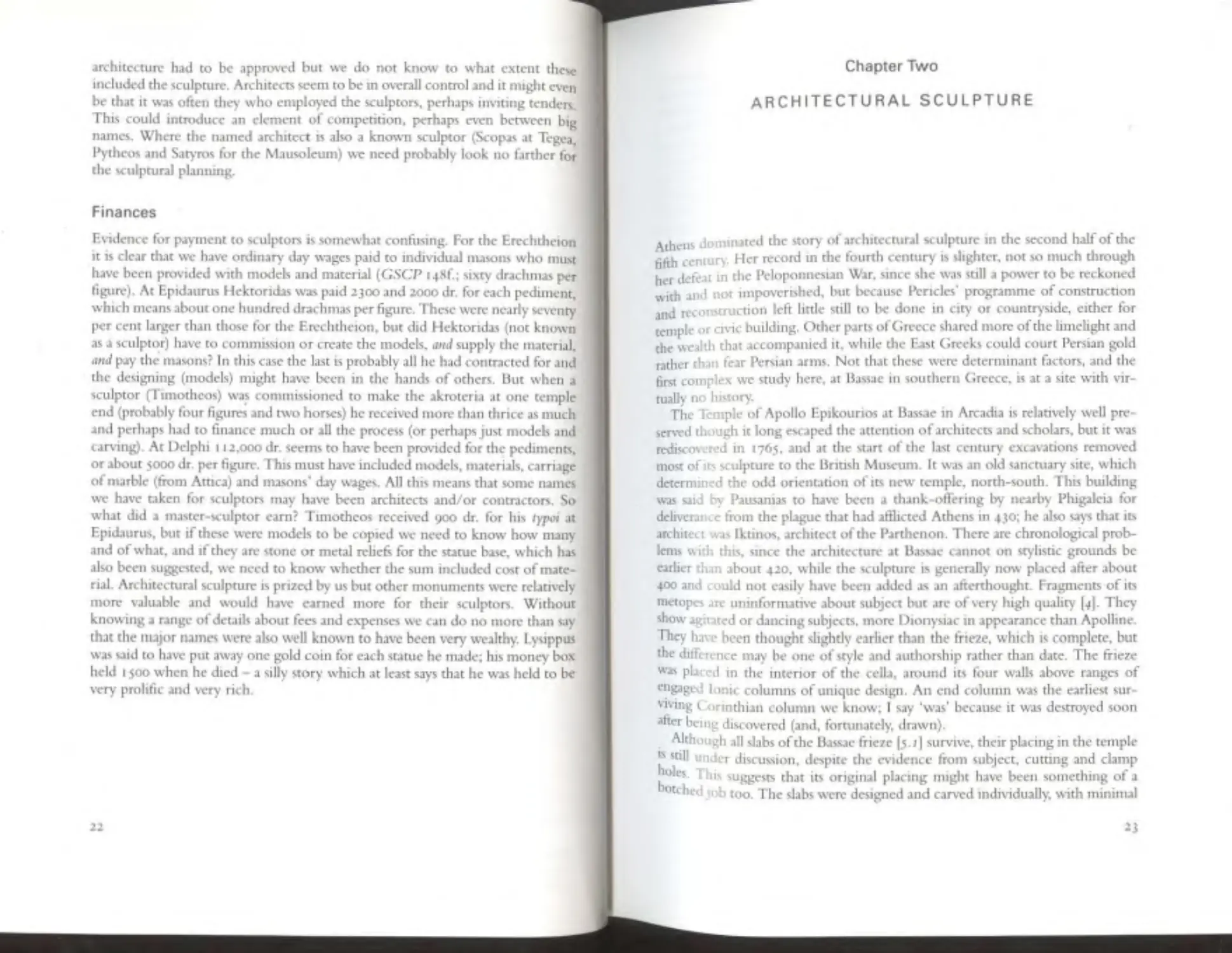

of" .trble, and in [1 J we see a marble statue being so treated by a sculptor on a

four ~-cenrury South Italian vase. The technique was assoc iated in antiquity

wit Praxiteles' name. In earlier days we assume that marble flesh parts usually

IJ

1 Apultan Y1SC. Statue of Hcracle)

bemg paimed A boy he<1ts the

tooh (~pa.tulae) m br.~z1er to left

while the arnst apph~ the \VJX

p:um; wa.tched by L.eu~. N tkc

and a real Heraclc,. About 37o-36o.

(New York so.rq)

carried a rather fl at wash of white for wom en, brown fo r m en, enhanced o nly

by such poh~h as the surf.1ce may have been g iven by th e masons.

T h ere are more monuments and figures to which absolute or close dates can

b e given from insc r iptions or texts than th ere were in the fifth century.

Nevertheless, progress of style in th e fourth century is not as easy to ch art as it

is in the preceding two cenruries, where stylistic datin g ro quarter ccmuries or

closer IS plausible. I am referring to styhstic dating by overal l in spection, at first

s1gh t, not dependent on more archaeological analysis of detail or techmque,

w hich may be more respons1ve. For instan ce, the date ofa fifth-century Amazon

type (GSCPfig.190a) was proved by archaeological analysis ofher rem-belt after

suggesn ons that tt was far later; and study of Hermes' sandals [z5[ seems to

confirm the place of t!m famous figure later than the fourth century, whatever

the date of the ortgm al type. Problems over the Delphi Acanthus Column [1 5[

arc reveali ng; tts date depends on inscriptions, bur these have been va r iously

mterpreted and scholars have found 1t possible ro accept a date e1ther before 373

or well after 335 Without any decisive arguments based o n style intervening.

Several wo~ks once confidemly assigned to the fourth century are n ow placed

rwo cencu n es later. A gen era tt on ago scholars were p rone ro try to date their

material as early as possible; current revision seem s ve ry ready to find merit in

dattng much later , and ca n not always be wrong. M ost ofthe 'about' dates given

m my capttons should not be taken too se riously, especially for the originals of

cop1es, but 111 some cases we can be certai n to the year.

Perhaps we sh ould accept that th ere was change rath er than progress, and it is

usually p~ss1ble to find that the change is associated with a major sculptor or

sc hool. Certainly, m ost modern and anc ient accounts of fo u rth -century sculp-

ture centre o n what is be!t eved about the styles ofa few major names: deep-set

.

er the response- Scopas, languor- Praxitcl es; yet th ere are many well-

eyesdtn~ )·mous monuments which might be better guides. When Pliny said

date anon

.

rapped' 1n the early third century he probably meant that there were

that art '

·

hh'

fGkI

Fh'

name-pegs on w h1ch to attac IS account o ree scu pture. o r 1m

110

moret•d in the mid-second century, which is w hen R omans began to take a

Jt re-star ...

I · erest m the Classical styles of the fifth / fourth century.

bve V

111

h

fh ds

'th h·

s;..·b •ic change is most apparent m t e tream1ent o ea , w1. pat enc

.

· , ;,m o r traits of real portraiture. Then there IS the mrroducnon of the

~xp~ nude. already remarked, where before the nudity was a function of its

cnb

1

et 'nathetic appeal, imnunent rape, cult fcrtt!ity, etc.) . Frontality of pose for

su ~e ..-

.

dh

.

..

W.

standmg figures is less donu nant an t ere are m ore rw1stmg .compositions. e

cxplam this by thinking that new concepts of space were bemg reali zed m the

d~s1gn of such figu res, but are no little led by the 'vay they are displayed in

mmeums today and what we arc able to do w ith our ca meras. Certainly the artist

was begmning to approach the modelling of his figu res in a different spirit but

we can'not easily judge how well o r deliberately th is was conveyed in display. In

anttqmry th e Riacc b ro n zes (CSCP fi gs .38 -9) may well h ave been set shoulder

to shoulder, no little obscured by thei r missing shi elds, not given the freedom of

a whole gallery or the artist's studio, an d it could well be that even Lysippus'

Apo>.yomenos [J5) also stood against a \vall. Praxiteles' Aphroditc [z6) was dis-

played at Cnidus to provide a view fro m behind, bu t the consideration th ere may

have been as much erotic as aesthetic, and not necessari ly the dominant reason

on gmally (after all, the Parthenos could be viewed fro m behind too). Relaxed

standing figu res of the fifth century are composed m a fairl y simple contrappos1o;

m the fo urth century there is more experiment with figures whose weight is

largely transferred to a support [z7,J9,70]. sometimes of a naturalistic character,

like a tree trunk. But even th1s composttton is p resaged in the fifth century

(CSCP figs.1 95, 216). Several of the fourth-century sculptors are said to have

wnttcn treatises about proportions, as d1d Polyc!ttus in h is Canon (CSCP 205),

yet the variants we can detect are not very striking, beyond a gradual chan ge

towards the shmmer, small er-headed, deliberately established by Lysippus as an

Improvement on Polyclitus. R ealisti c representation of the human body, w hich

was srill the basic aim, does not allow of much variety, but the artists saw the

Importance ofdefinmg their intentions an d methods and seem ed to have spent

no little time on theory.

T he fi fth centu ry had exper imented with m ost treatme n ts o f dress, from

VIrtual geometry but of differe nt purpose in the Late Archai c and Early Classical,

to hvely massing of cloth an d even appare nt transparency. The fourth century

nngs the ch an ges, with occasional in terest in matters su ch as showing cloth fo lds

not Iron ed-out (press folds) and some c rinkly an d crumpled textures. The ladi es

~;ove steadily, even predictably, it see?15.' fro m the d eep-bosom ed C la ssical to the

gh-glrt Emp1re - h n e of th e I lellemsttc, and there are changes m hatr styling,

tntroducm!o the 'melon' c oiffure. There was not a great deal n ew u nder the Later

15

Classical sculptural sun until th e true Hellenisti c of the late century, and the

gradual replacement of C lass1c1sm w ith somethmg more demanding ofsculptor

and viewer, though not necessarily more satisfYing or functionally effective.

Many of the sc ulptural monuments ofthe Archaic peri od, and virtually all of

the fifth cen tury, were still visible to th e ar tists of the fourth. The Archaic, with

their strictly unrealistic appearance but wonderful patterning of body and dress,

acquired an aura ofsanctity, which was natural enough give n both the apparent

vene rability of their appearance and their placing m sanctuaries. There is a

measure of deliberate arc haizi n g throughout the Classical period, sometimes

prompted by the need to represent a culr statue in some mythological si tuation

[5.5, 10.5]. Where a traditional monument, such as a herm, had to be carved, the

features are usually updated though the general form remains Archaic (GSAP

fi g. 169; GSCP figs. 142,189), and there is the same degree ofarchaizing fo r mask-

like features, notably for Dionysos [69]. It is not clear to what extent the archaiz-

ing of the H ellenistic period which we recognize in highly mannered relief

figures with swallow-tail ends to their dress a nd fan ciful flaring an d zigzag pat-

terns, had 1ts origins in fourth-century sc ulpture, but the style is to be found m

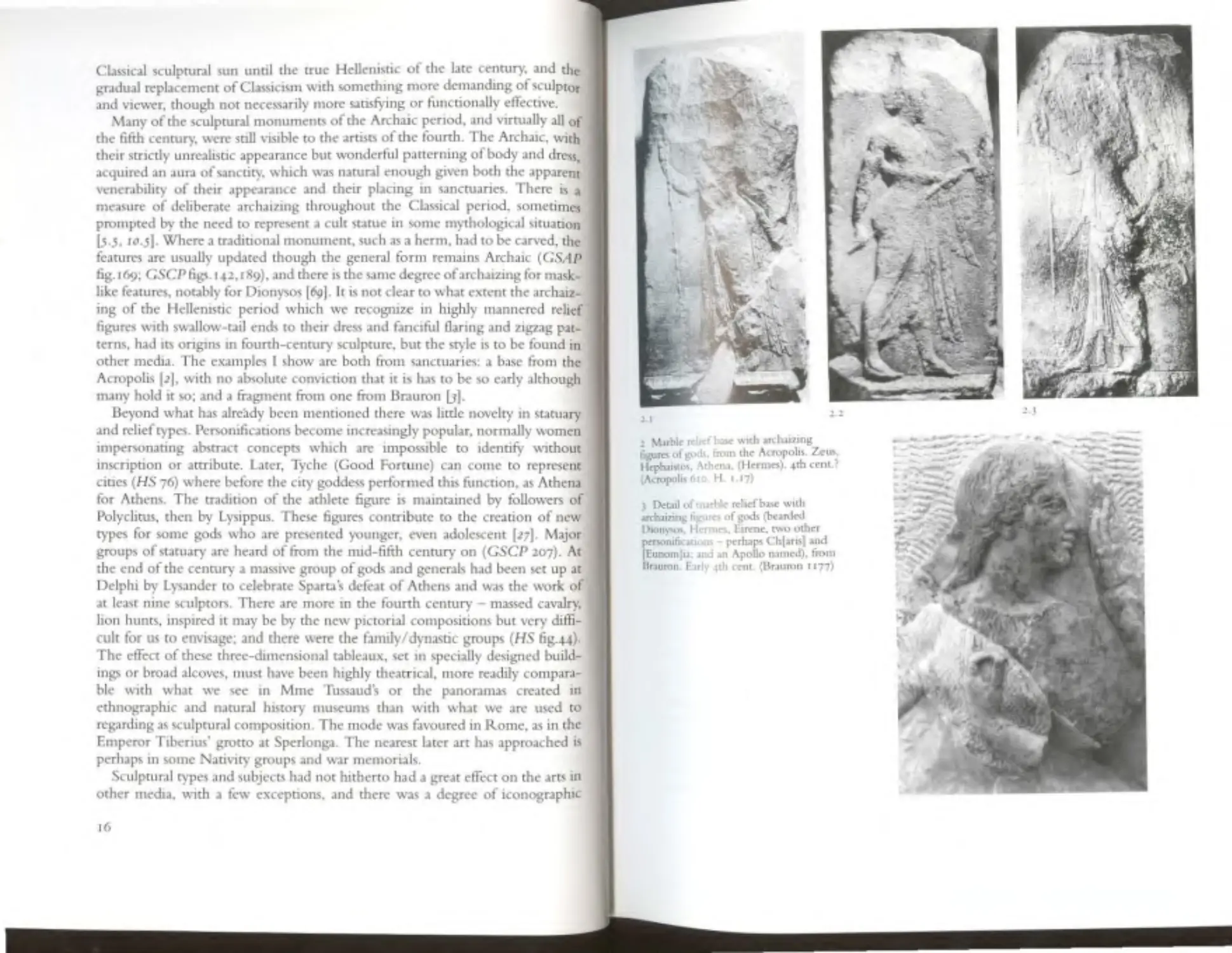

other media. The examples I show arc both from sa nctuaries: a base from the

Acropolis [zj, w ith no absolute convictio n that it is has to be so early although

many hold it so; and a fragment from one from Brauron [J].

B eyo nd what has already been mentioned th ere was little novelty in statuary

and rel ieftypes. Personifications become increasingly popular, normally women

impersonating abstract concepts which arc 1mpossible to identifY \vithout

in scription or attribute. Later, Tyche (Good Fortune) ca n co me to represent

cincs (HS 76) w here before the city goddess performed this function, as Athena

for Athens. The tradition of the athlete figure is mai ntain ed by foll owers of

Polycl itus, then by Lysippus. These figures contribute to the creation o f new

types fo r som e gods who are presented you nge r, even adolescent [27]. Major

groups of statuary arc heard of from th e mid-fifth century on (GSCP 207). At

the end ofthe century a massive group ofgods and generals had been set up at

D elphi by Lys.1nder to celebrate Sparta's defeat o f Athens and was the work of

at least nine sculptors. There are more in the fourth cenrury - massed cavalry,

lion hunts , inspired it may be by the n ew pictorial compositions bur very diffi-

cult for us to envisage; and there were the family/ dynastic groups (HS fig.44).

The effect of these three-dimensional tableaux, se t in speciall y designed build-

ings o r broad alcoves, must h ave been highly theatrical, more readily compara-

ble 'vith what we see in Mme Tussaud's o r th e panoramas c rea ted in

ethnographic and natural history museums than with what we are used to

regarding as sc ulptural composition. The mode was favoured in Rome, as in the

Emperor Tiberius' grotto at Sperlonga. The nea rest later art has approached IS

perhaps in some Nativity groups and war memorials.

Sculptural types and subjects had not hitherto had a g reat effect on the arts in

other media, with a few exceptions, and th ere was a degree of iconographiC

16

.: M;arblc rdirfb >t' "nh n c h;uzmg

tigum of gods from the Ac ropo hs. Zeu\,

tlcphotl\tO!I. Achena , (Ji ermes). 4th cem. ?

v~.cropolis 610 H . 1 17)

3 Det.ul ot nurble rehefba"te wnh

;arch•izin~ figures ofgods (bearded

DIOnV'-0'1. Bermes, Em: ne. two other

p<"'>~Jficanons p< rlups C h[ms) and

fEunom}u: and an Apollo named), from

Brauron. F .arly ..t .th cent . (Uraumn IT 77)

autonomy in the various crafts des pite the overall homogeneity of style, and

regardless of scale or mcd1um. This begins to break down, a nd we can find

Important figures and groups re produced in small bronzes, even jewellery, and

later in painting also and on marble reliefS. Even a cursory rev1ew of the figure

types on coins and engraved gems reveals that increasingly through th e later part

of the fifth century, and especially in the fourth, th ey seem to present versions

of statuary types and groups. Sometimes this can be proved, but we are entitled

to believe th at many others rep eat types that may not have survived through

copying, and they present as many varian ts as arc often attributed to the inge-

nuity of late copyists. Many sta ndard stat uary types arc created, and many sur-

VIved from the fifth centu ry. The conventions are obv1ous in portrait figures,

with different types for pohtiCians, generals, poets, philosopher<;. D eities are pre-

sented in a comparanvcly restncted range ofseated , standmg, lcanmg poses, dis-

Cinguished only by attnbute or details o f dress and gesture. These, whether in

sta tu e, reli ef, coin or gem, were the images in whiCh the Greek conceived his

gods. They were detcmuned by the way they had been prese nted by artists, nor-

m ally in sculpture, rather th an from significant n arrative images which h ad been

equally infl uential in earli er years (the threatening figures ofa Zeus or H eraclcs).

In this ifnothing else is d emonstrated th e importance ofscu lpture to our under-

standing of the anc1cnt Greek, h is visual experience and his society. And I feel

no compunction about using th e word 'his' in this context . Evcrythmg we have

learned about the role and education of women in ClassiCal urban society sug-

gests that they neither aspired to n o r were allowed any real contribution to major

aesthetic d ecisions except probably at a domestic level (w eaving, but not even

pottery; music-making and rel evant compositions), and were even restricted in

their opportuniti es to contemplate the results. It is no comfort to think that they

were probably worse off in other ancient societies, an d far too late to do any-

thing about it. The attem pt t o project back into Classical antiquity the responses

and preoccupations of the late twentieth century is n o sort ofscholarl y contri-

bution to our understanding of th e past, however much fun it may see m to be.

Whenever we admire what seems to be a sympathetic treatment of the female,

as brave, compassionate or loyal, we need to remember that 1t was almost

certainly devised by a male, for whatever reason.

Pla ces, Patrons and Planning

Athens and Attica domjnated the story of G reek sc ulpture in th e second half of

th e fifth century. Defeat by Sparta at the end ofthe century is not the ma in reason

for Athens' slighter record aft erwards sin ce sh e soon regained power and a d egree

ofwealth, but in m any respects we might regard the city's Pcriclean architectural

programme of building and rebuilding, both civic and religious, virtually com-

plet e, and there were no disasters ofthe type that occasioned new temple build-

ing, with sculpture, elsewhere in Greece. Private commissions, for d edi cation o r

18

an 1mportant source indeed the grave monume nts increase in lav-

· e'\ ren1atn.

•

.

.

gra' ·

d mbcr until they were notably dmumshed by a sumptuary decree

h'."an nu

d..

1'1

" · b D ·metrios of Phalcron, puppet governor fo r the Mace omans 111

passed _Y1

·e however, clear that Athens remained the home of a high propor-

~--lo , tls.

h

h

3.1

• f h fc rth -ce ntury sc ulptors whose names were thoug t wart rcmem-

00110t~0~

.

b ·nng bY anocnt wntcrs.

.

.

c O tll c;cities of central and southern Greece play a more prormnc nt part m th e

d s East Greece where adjacent Persian ru le was n o longer threatcn -

'tory. as oe

.

·

d·

h

·I ·1 later 111 the century Macedoman patronage attractc mterest to nort

tng'"11e<

•

''. . A.ll this apphcs mainly to architectural sc ulpture but pnvatc monuments

Greece. •

fIhdbII

I S w 1dely distnbutcd. While gravestones o qua lty a een arge y an

~00 ~

h

Ath cman phenomenon, they can now be found everywhere. T ere was some~

thing of a boom m sc ulptural dcdjcati~n at the nanonal sanctuanes of Dclph1

and Olympia, promoted by states, pnvate persons and eventually dynasnes,

ted bv a range o f works from maior bronze groups to a plethora of

rcprcscn

,

,

.

small reliefs. Public monuments arc commoner, one of the fun cnons m et by th e

new portrait statues.

.

.

MaJOr artists had alway s been relatively mobile .though there was a lingcnng

tcndcn cv for them to be favo u red for home commiSSions. The ev1dence ISscan ty

smce w~ have to rely on mentions in later texts and th e occasional excavated and

signed base. Leochare\, like Alkame n es before hi m, seem s seldom to have left

home 111 Athens. Other sculptor<; ranged farth er afield on comnlissions, to the

cast and by the Clme of Lys1ppu s, to the north, and h e also exec uted works for

Tarentum 111 th e west. Work by East Greek and some homeland sculptors for

native kmgdoms in As.a Mmor and elsewhere in the east m~y have been the

source for some new sc ulptural forms that were to have an Im portant future :

sculpture for hero-shrines (heroa), relief sarcophagi , and there \vas a slight

renewed 1warencss ofeaste rn, generall y Persian, fo rms, but nothi ng like any new

onentalmng movemen t.

The orgaruzation of any maj or state commission for architectural sculpture

ca n be judged from the ev1dcn cc for the better known commissions for archi-

tecture, all part of the same planrung operation . Ep1daurus is an important

source, as we shall sec, but 1t would be good to know more about this, not just

about the finances but fo r whatever bght mjght be shed on decision-making

about des1gn and subjeCt matter. To what extent were the subjects of temple

sculpture dcternuned by patrons, priests, artists, or even the public? We learn

from ms riptions that architects were appointed by the citizen Assembly on the

recommendation of th e Council, or by com parable bodies in various cities, an d

m sanctuanes by committees kn own as Naopoioi or Hieropoioi (at D elph i and

Delos .., .pectively). Sculptors get mentioned only where it was a m atter of

paying sculptor- masons (for indi vidual figures and groups on the Erechtheion,

GSCP - 48--9) or recording contracts (Epidaurus), with no indication of deci-

Sion ab, ·: mbJects. Prcbminary plans (syngraplwr) and models (paradeigmara) for

19

+ Archaic

0 Classica l

BLACK

+ Daskyloon

+ Dorylaion

P HRYGIA

0

. ~·0

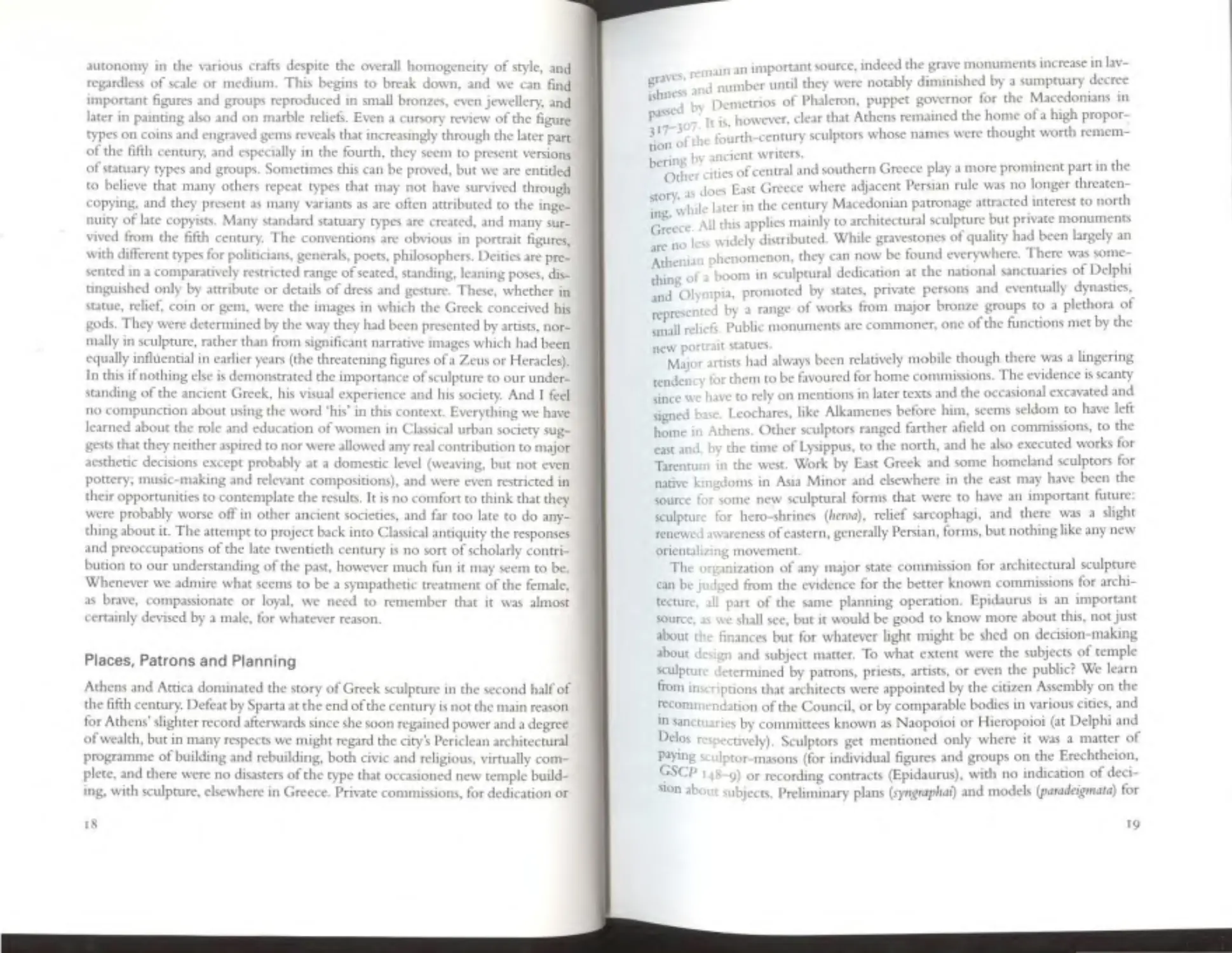

Greece and The A e gea

fArch• •c •nd Clm

n World

ocal G"'ek sculpru "'·

11 soun:es o

tndtcanr ? prtnCip h. l ume.

uoCSAp. S(:p•ndt os'"'

d iU usrr.lt('d

dlscussed an

architecture had to be approved but we do not know to what extent these

included the sculpture. Architects seem to be in overall control and lt might even

be that it was often they who employed the sculptors, perhaps mvmng tenders.

This could imroduce an clement of competition, perhaps even between b1g

names. Where the named architect is also a known sculptor (Scopas at Tegea,

Pytheos and Satyros for the Mausoleum) we need probably look no farther fo r

the sculptural plannmg.

Finan ces

Evidence for payment to sculptors is somewhat confusing. For the Ercchthe1on

it is clear that we have ordinary day wages paid to individual masons who must

h ave been provided with models and material (GSCP 148f.; sixty drachmas per

figure). At Epidaurus H cktoridas was paid 2300 and 2000 dr. for each pedime nt,

which means about one hundred drach mas per figure. These were n early seventy

per cent la rger than th ose for th e Erechtheion, but did Hektoridas (not known

as a sculptor) have to commission o r create the models, a11d supply th e material,

a11d pay the m ason~? In this case the last is p robably all he had contracted for and

the designing (models) might have been in the hands of others. 13ut when a

sculptor (Timoth eos) was com missio n ed to make the akroteria at one te m ple

end (probab ly four figures and two horses) h e received more th an thrice as much

and perhaps had to finance much or all the process (or perhaps just models and

carving). At Delph1 112,000 dr. seems tO have been provided for the pcdimcms,

or about 5000 dr. per figure. This must have included models, materials, carnage

of marble (from Attica) and masons' day wages. All th is means that some name'

we have taken for sculptors may have been architects and / or contractors. So

what did a master-scu lptor earn' Timotheos received 900 dr. for his typoi at

Epidaurus, but 1f these were models to be copied we need to know how many

and of what, and 1f they are stone o r metal reliefs for the statue base, which has

also been suggested, we need to know whether the su m included cost of mate-

rial. Architectural sculpture is pr ized by us but oth er monuments were relatively

more valuable and would have earned m ore for their sc ulptors. Without

knowing a range ofdetails about fees and expenses we can do no more than say

that the major names were also well known to have been very wea lthy. Lysippus

was sa id to have put away one gold coin for each statue he made; his money box

held 1500 when he died - a silly story which at least says that he was held to be

very proli fi c an d very rich.

22

Chapter Two

ARCHJTECTU RA L SCULPT URE

Athens dominated the story of architectural sculpture in the second half ofthe

fifth cenrurv. Her re cord m the fourth century ISshghter, not so much through

her defeat 111 the PclopomlCSian Wa r, since she wa; sull a power to be reckoned

with and not Impoverished, but because Pencles programme of constructiOn

and reconstr ucnon left little still to be done in city or countryside, either fo r

templ e or ovic building. Other parts ofGreece sh ared more ofthe limelight and

the we alth that accompan ied it, whi le the East Greeks could court Persian gold

rather tlun fear Pers1a n arms. Not that these were determinant f.1ctors, and the

first complex we srudy here, at 13assac in so u th ern G reece, is at a site with vir-

tually no hiStory.

T he Templ e of Apollo Epikourios at Bassae in Arcadia is relatively well pre-

served though 1t long es caped the attention of architects and scholars, but it was

rediscovered in 1765 , and at th e start of the last century excavations removed

most ofits sculpture to the Bnnsh Museum. it was an old sanctuary site, which

deternuncd the odd orientation of Its new temple, north-south. This building

was <a id bv Pausanias to have been a thank-offering by nearby Phigaleia for

dehveran e from the plague that had afllicted Athens in 430; he also says that its

archite<'t \3S lktinos, architect ofthe Parthenon. There are chronological prob-

lems wnl th is, sin ce the archnccture at Bassae cannot on stylistic grounds be

earlier th.n about 420, while the sculpture IS generally now placed after about

400 an d could not eas1ly have been added as an afterthought. Fragments of its

metopes arc uninformative about subjeCt but arc of very h1gh quality [4]. T h ey

show ag1tated or danc ing subjects, more Dionysiac in appearance than Apolline.

They have been thought slightly carher th an the frieze, which is complete, but

the difference may be one of style and authorship rather than date. The frieze

was plau·d 111 the interior of the cella, around its four walls above ranges of

engaged l omc columns o f uni que design . An end column was the earliest sur-

VIving Connthian column we know; I say 'was' because it was d estroyed soon

after being discovered (and, fortunately, drawn).

.

Although all slabs ofthe Bassae rrieze [5.1j survive, their placing in the temple

IS st1U unde r disc uss ion, despite the ev1denc e fro m su bject, cutting and cla m p

~ales. ThiS lllggcsts that its original placi n g migh t have been somethi ng of a

otched) ~b too. The slabs were designed and carved individually, with minimal

23

instances ofoverlapping. As an interio r frieze they m ust have been virtually invi~

lble unless there was some lighting through the ceiling. There are two major

themes, each occupying one short and one long side: an Amazon omachy involv-

ing both ThcseUI an d H cracles [5.Z,J]. and a Ccntauromachy [5.4,5]. It is, 1

thin k, unl1kely that any of the Amazon scenes refer to Troy. Odd men out are

an Amazonomachy slab on the west (left) and the Apollo and Artemis 111 a

char iot drawn by stags (n orth), which IS easier to relate to the Centauro m ac hy

(recall Apollo's presence in the O lympia Centau romachy, not so far away, GSCP

fig. 19), than to th e fight with Amazons, whom Artem is nught even favour. We

are far fro m the pohtical symbolism ofAthenian Classical sculpture here, a nd the

subjects m ust carry other m essages. The Amazonomachy is perhaps th e more

difficult to explain except in terms of the general populanty of the theme.

The style is distinctive. The figures arc rugged, big-headed and almost squat

m proportions, the carving rough yet confident. In sculptural terms one thinks

ofthe thick-set Polyclitan figu res, but there is more to it than this, and in com-

petence or provmc1ahty arc unjust accUiations to level against scenes of such a

vigoroUIIy successfu l na r rative content. Most fighting groups are traditional b ut

not always readily match ed in sculpture. The ccntaur k icking back .n a Greek

(north) was last seen a centu ry before on a vase, and the dramatic (and not ve ry

successful) foreshortening ofa fallen ccntaur beneath them (we sec the top oflm

head) suggests pictorial inspiration, since this wa> a period whi ch entertain ed t he

first trompe l'oeil pai ntin g in Greek art. The frieze has no o bvious predecessor

except, gene r ically, the great compositions of H1gh Class1cal art of the preced-

mg half century; no r had it a followi ng, yet it IS squarely in th e tradition of the

classical na rrative fr iezes, wit h details such as the flying dress in the b ac kg rou nd

an d treatment of drapery and anatomy.

The sanctuary ofH era som e ten kilometres from the nch and important city

ofArgos lost its tem ple to fire in 423. Polycl itus (who was an Argive) had made

a chryselephantinc statue for the building (cf. GSCP fig. 207), but perh aps

earlier, though 1t was su re ly mstalled 111 the new temple w h ich \vaS being built

towards the en d of the cen tu ry. Pausamas' descr ipt ion helps us With the sculp -

ture, imp lying that the pediments sh owed the B irth ofZeus an d the Sack o fTroy,

neith er immediately relevant ro Hera although she was involved, and the

metopcs, at the ends only, a G 1gantomachy and an Amazonomachy. All bu t the

Bi rth (if th is is in deed what 1t \vas) are famili ar from the Athenian buil dings of

the gener ation before. The re m ai ns arc scrap py and cannot be expected to reveal

much about Po lyclitan rehef com pos1t1on; indeed they seem more a re fl ectio n

of what m1ght be expected of mainstrea m Greek work between the Parthenon

and the fu ll fo u rth centu ry. B ut there are some striking action figures (6] and

expressive heads. N1cer . and no less significant, IS the carving of th e gutter [7].

mtroducmg a vers1011 of the new acanthus and ;croll scheme winch IS going to

play a very important role in later arclmectural decoration.

Scraps from a temple at Mazi in Ehs, twen ty k ilometres from Olympia, arc in

rabic to both Bassae and Argos, and indicate a pedunental

k c"mpa

a se}

·h' 1 show one giant's head with magmficcnt stanng eyes and a

Gglllona< ,.

1'·

1 hioncd as a sea-monster 's h ead (ketos) [8].

hel!llct

3

'

·

d.h

•-h

·

..,.

I fAh

11 •IJe Peloponnese, at Tegea 111 Aica 1a, t e £UC a1c . emp e o t ena

Sn11·

·

Ih.

f

.

._

rnt down in 395 / 4· Pausamas says that Scopas was t 1e arc ltect o

A]ea" 1

,.u

·

d·bh

d

I llel1t which >eems roughly m id-century. H e csc n L'S t e east pe -

he rep ace1

,

1

d ·tall and gives the subject of the west. T he m ost fa mous hero1c h unt

JOJellt In C

d.

.

db

·.

" was that for the Calydonian Boar , an Area 1an ep1so e ut n ot

of ann• ·

1"

1a1

d .. Arradia Nor h ad the story anythmg to do With Athena or the oc

locate 1

'

·

·

b

odde" '\lea whose ro le she h ad adopted. 13ur the hcromc was anoth er rave

g . nd an Arcadian princess, Atalante, and the H unt was th e su bject of the

v1rg111 a

.

,

..

·

1h

·

·d:mcnt. At the west was Ach illes expedmon agamst Te ep os, a pn nce

east pc

d·d.d]

ofM pia 111 the Troy area, 111 what \vas a premature an m1s 1recte pro ogue to

the Tropn War. The few fragmen ts can read ily be placed to show the Hunt 1n

convennonal form, though only the pig 111 th e m iddle can be confidently

located; and from the battle one head w ith a honskin cap is likely to be Tclephos,

who was a son of Hcracles, while a helmeted head IS convemencly asc n bcd to

Achillt~· but might be anyone [9.1,2]. There are more substantial p ieces of two

of the ,orncr akroteria [9.J]. The relatiomhip of th e sculpture to Scopas IS

ruscussc 1later, but the heads are good, early examples of the pathetic gaze and

there 1s 1 certain dramatiCswirl to the figures. The vigour ofsome of them was

anncip. ed •t Argos. We learn most about the metopes from inscriptions o n the

arch1tra1 =beneath them, one of which names Telephos and lm mother Auge,

so 1t seems that they told someth ing of the f.1mily histor y. Auge had been a

priest~· at Tegea, raped by H eraclcs, an d this also explains th e subject ofthe west

ped11n e .

A;klep!os, the god ofhealing, \vas a re lau vely new deity for Greece. H 1s pr in -

cipal sanctuary at Epidaurus began to attrac t new building in t he late fift h

centurY, about the time h1s cult was taken to Athens (cf. ARFII II fig. 305). and

m the tourrh century there were many new buildings. T h e god's new tem ple

was completed by around 370, to j u dge !Tom style (but see b elow) and m sc ri p-

tions. It was small but very elaborate and r ichly furnish ed, including a ch rysele-

phanun ~cult statue by Thrasymedes ofParos. The architect was Theodotos, and

a Theo. with Timothcos made the akrotena. T he latter also made typ(ll, an d

one pedm1ent was made by H ektor idas . T he rypoi (possib ly reliefs for th e statue

base) . ,

other information from building accou nts have been discussed in

Chapte• One. Ancient authors say nothing about the oth er scu lpture but lt is

well enough preserved fo r us to be sure about subjects and reasonably sure about

restoration of groups.

The <">t ped1men t had an Amazonomachy (10.1 -J], the east t he Sack ofTroy,

Identifiable irom fragments of t\vo diagnostic scenes - P riam being mu rdered

fro.4]. and the statu e clutched by Cassandra, re n dered in an appropr iately

Archa1c nunner [ 10.5]. Asklepios' so ns provided th e medical ser v1ce at Troy, and

25

this may have been enough to justify the subject here, but then th~

Amazonomachy would also need to be the Trojan one which is surprismg bur

not impossible. Stylistic differences between the pediments arc reasonably held

to reflect the work of d1ffe rent artists, which is what the mscnpnons mdicace.

The corner akrotcria arc Nika1 and woman riders [11]. taken to be Aur.ti: per-

somficanons of hcalmg breezes, one \\~th clinging dress, the other more natu-

rally clothed, as 1f to differentiate identity or function. The central akrotcria arc

a N1kc and a group, thought to be Asklepios' father Apollo encountering his

mother. The style ranges fro m figures and dress that seem to hark back to the

late fifth century, With clinging drapery and the flying figures (cf. CSCP figs.

115-<). 139) to dramatic expressiveness of pose and features that annc1patc the

work of over a generation later. The novelty is not immediately taken up else-

where, yet the date suggested for the Epidaurus sculptures cannot be far wrong.

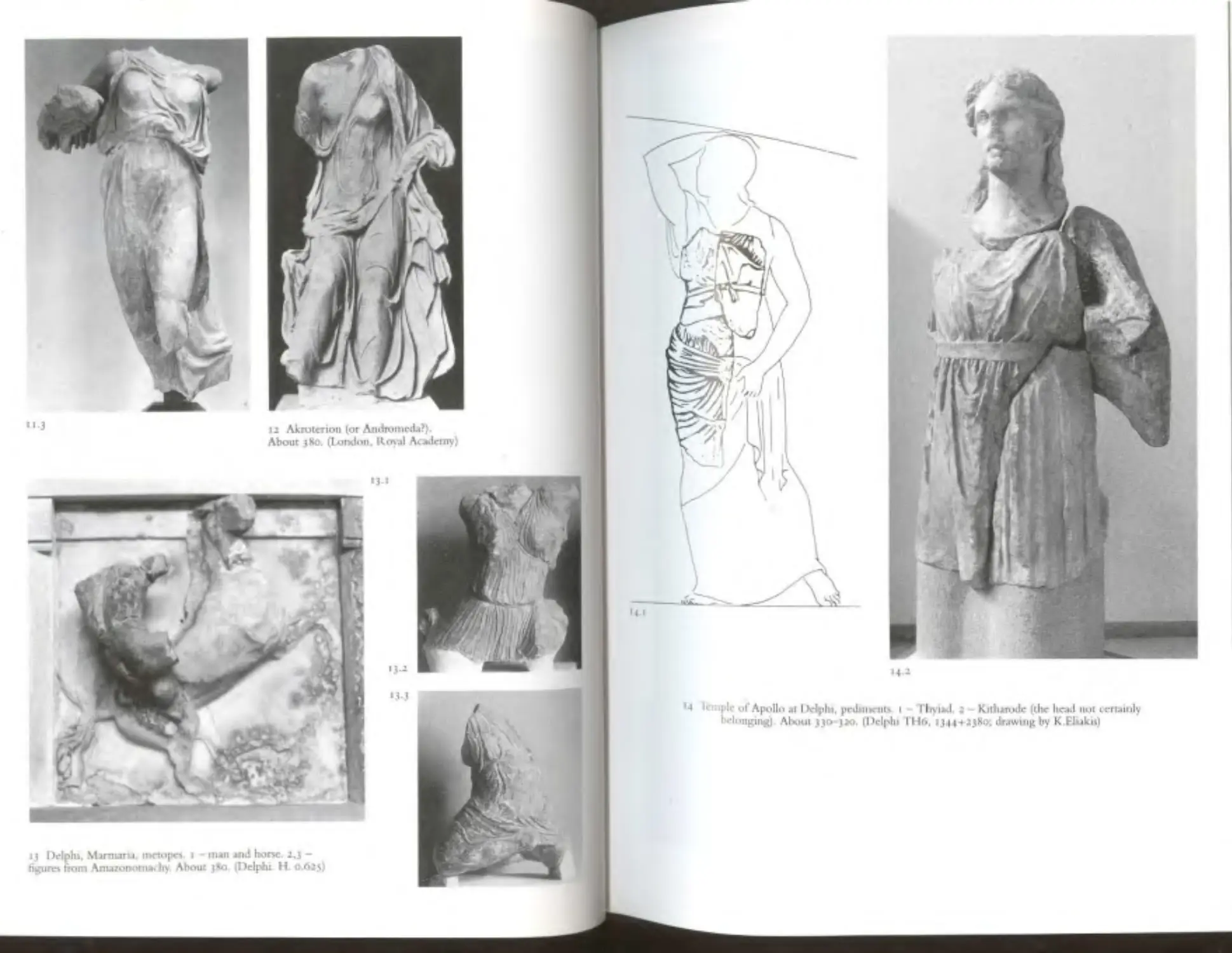

I add here a fine piece in the R oyal Academy in London [12) for its broad sun-

ilarity; lt recalls Ep1daurus but may be from an Attic building. The general type

is a popular one, represented too by finds in Athens, and may be seen as succes-

sor to the Nikc types ofth e later fifth century, as that ofPai onios (GSCP fi g. 139).

M ov ing north now, to central Greece and Delphi, we find on the lower

terrace (Marmaria) a strange an d bea utiful circular building (the Tholos), built a

little before th e Epidaurus temple. lt ca rried forty mctopcs on the exterior,

another forty around the inner r ing wall. Its architect was a Theodoros (o r, 1f

our source V1truvius mistook a Thcodotos, we would have a link w1th

Epidaurus). The subJects of the o uter metopes were Amazonomachy and

Ccntauromachy - a well-tried combination - but th e most mccllig1ble remains

give us a man wnh rearing horse and a fight [IJ). Style and compositions see m

updated Classical. The morsels ofthe inner metopcs suggest lleraclean subjec ts.

On the mam temple terrace at Delphi we meet a different disaster a~ occasion

for new tem ple building. A landslide after an earthquake wrecked th e Temple of

ApoUo m 373· The ~culpture from the rebuilding is taken to be of the nos and

J205 and the ~culptors, ~ays Pausanias, were Athenian (Praxias, then

Androsthenes). H e also gives the pediment subjects: east , Apollo wnh mother

and sister (Lcto, Artemis) and Muses; west, Dionysos and Thyiades (ecstanc

attendants, hke maenads). For the last, part of the torso ofa woman wearing an

animal-skin IS appropriate [q .1) and there a re pieces of seated women, at a

shghtly ~maller scale, who should be Muses. The eas t pedimem figures are

thought to be slightly smaller than the west, perhaps because more numerom,

but this need not apply to any central group. The central Apo Uo is thought to

have been a seated figure, bm the two fragmentary candidates are ei ther too small

o r perhaps too big. There is a figure ofa standing kithara-playe r who would suit

identity and place [14.2[. and we would expect this to be its correct position.

H owever, it was found near the other e nd ofthe temple, and it has, though with

considerable d1~agreemem, been restored with a head (HS fig.79) that is surely

a Dionysos, to judge from the broad headband (mitra). and might be dated late r:

26

h accordingly been placed at the west. Dionysos was a respected deity at

bu:J i~~a~ut it is unparalleled to find him holding Apollo's kithara, and one

D Pd whether, high on the ped1ment, the shght d1fference 111 co1ffure woul d

"·on er<

h

·

·h

haw been apparent. The Thy1ades suggest t at Pausamas was ng t to see a

J)lom"IJC subJect at the west. The head 1s fine, and the androgynous features

ble 10 either god by tlm date recall a httle even the Cmdian Demeter [49].

~~t~mJOn ":nse suggests that we should have a ~tanding Apollo and a seated

r)1onysos a> cenrrep1eces. The other fragments g1ve little away and arc not par-

Jarlv impressive, but the whole complex and problem~ {the fragments have

~~~y b~cn recogn ized 111 recent years) g1ve a good example of the architecntral

(size). 1conographtc (identity) and textual (accuracy ofdcscnpnon) problems that

ay be mvolved in the study of arch1tccntral Kulprurc.

111

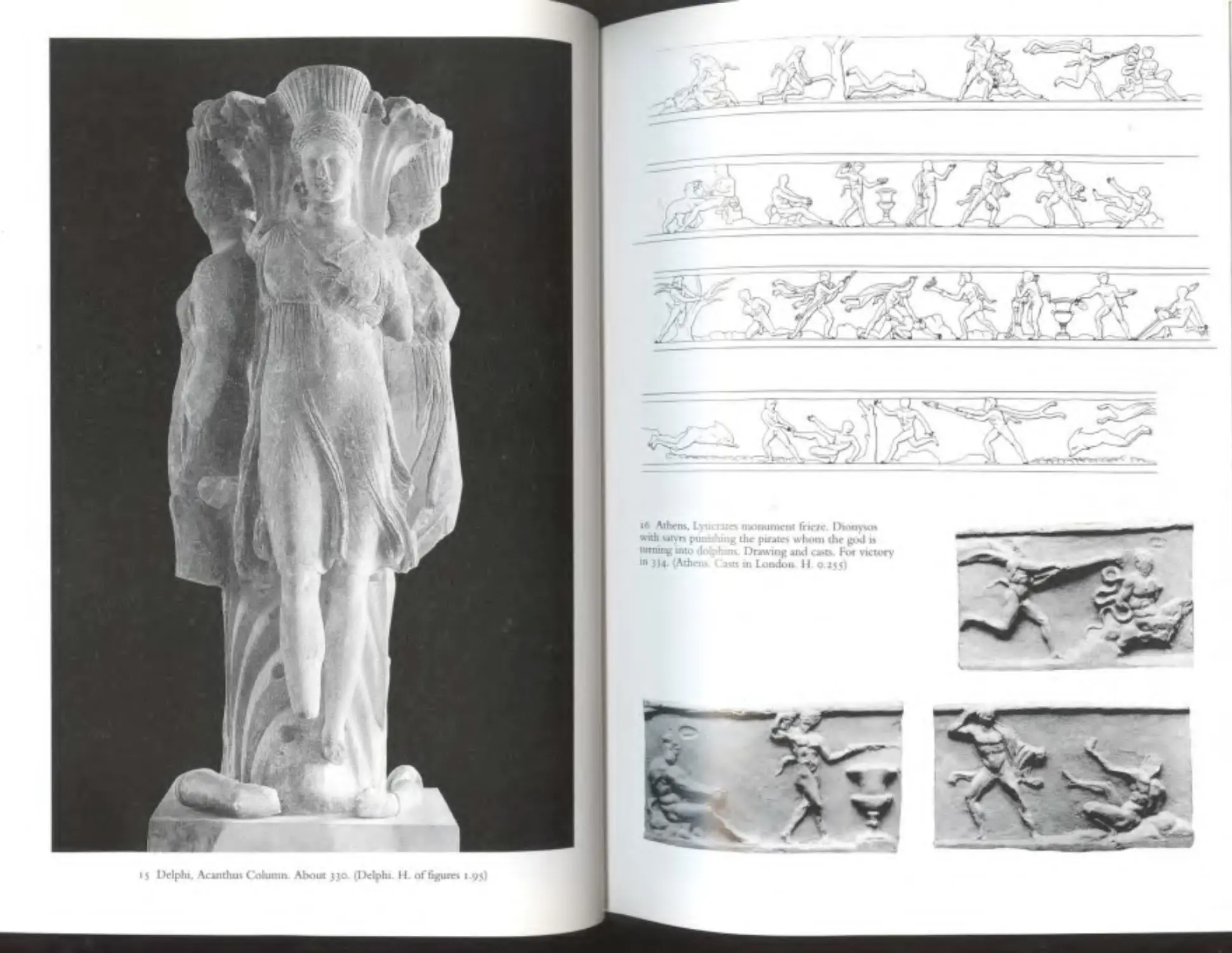

One last monument from Delphi has architecwral associations but is no part

of a bmlding. and offers no less vexing problems of interpretation than the

Templ e. The Acanthus Colu mn stood over thirty metres high, mainly composed

ofth e leafY plant that had been used to create the Corinthian capital. On it stood

a m pod between the legs of which arc three dancers wearing bas ket-shaped

(kalathiskt>s) crowns [15]. They arc gracious, broadly Pr axite lean in th eir appeal

ofboth features and gently swirling dress, but not o f prime execution; they were

after all set very high. On a base associated with it has been read {though not by

all) the name of Praxiteles, as well as indications that it might have been erected

before the earthquake of 373, and re-erected fifty yea rs later. Other readi ngs of

base and style prefer the later date. around 3JO . The fact that both Corinthian

columns and kalatltiskos dancers arc assoc iated with the name of the late fifth-

century arust Kallimac hos (CSCP 207, fig. 242a,b) may be fortuitous; the acan -

thus column seems a fairly popular fourth-centu r y conceit.

The only architectural sculpture of Athens to occupy m in this chapter was a

pnvate dedtcation, not public. Lysikrates had won a tnpod as a theatr ical sponsor

(clwrt;~os) m 334. H e se t 11 on a small cyhndncal but ld mg ofCorinthtan columns

that may haw sheltered a statue ofD1onysos, set on a tall square base. The bui ld-

mg can be seen mll JUSt cast of the Acropolis having survived through being

mcorporated m a Capuchin monastery. What is left oftlte frieze is iu situ . I show

drawmgs and photos ofearly casts [16). The figures are weU spaced, w hich is eco-

nomical a• wcU as making them better read at a considerable height.

The East Greek world was in a more comfortable and expansive mode in the

fourth cemury than it had been in the fifth, on good terms w it h the Persians and

later much favoure d by Alexander who was anxious to impress.

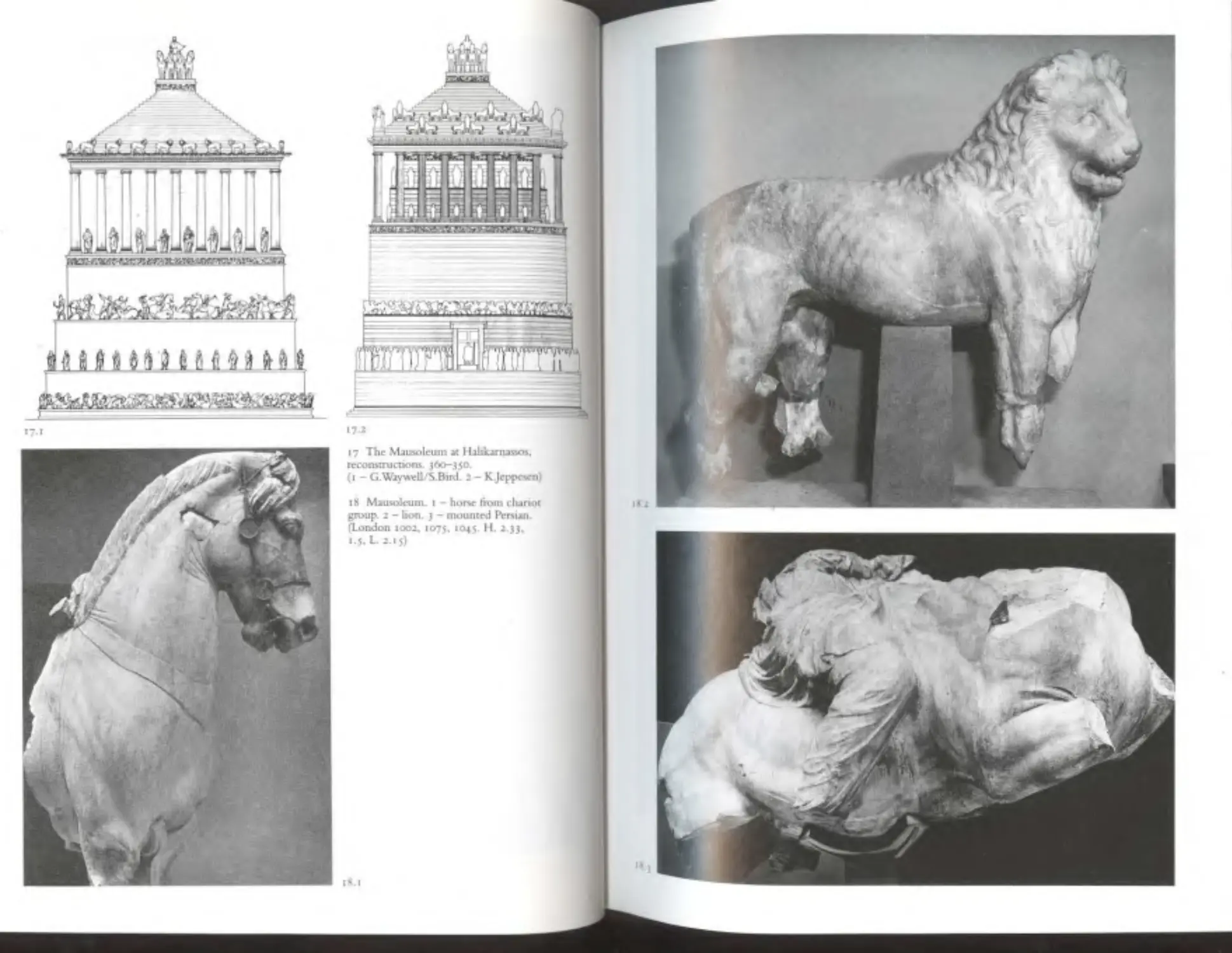

it ts an~ablc that the most important monument, the Mausoleum, should be

c~nslder~d with other work by Greeks for foreigners, later in this volu me, but

~e monuments considered there all owe no little to foreign taste while the

ausol~um owes nothing, except possibly deta il s of its form - the first of all

27

mau~olea. MausolUI was king of Caria, then a semi-independent kingdom

Wi thm the Persian Emptre. The king had planned his new capital

H alikarnassos, a donunant feature of which was to be h is tomb, so It was pro~.t

ably planned and could have been started by about 36o. H e d1ed 111 353, followed

by lm wife Artemisia 111 35 1, bur work continued to complenon , probabl .

shortly afterwards. Texts sugge>t that Artemisia was a major driv111g force In th~

proJect. The Site was thoroughly pillaged for building material but much rehef

sculpture was blll lt Into wa lls ofthe fort at Budrum a nd a cache ofsc ulpture was

excavated near the Site. A combmation of excavatio n and a descripnon of th.

building by Phny has produced o nly roughly agreed results about overall appear~

ance and plac111g of sculptu re, but recent work on the architectural remains ha,

helped ch nu nate some possibilities. I show two schemes now favoured [1 7]. The

whole was some forty-five metres high. The main friezes must go on the

podium, but there \vaS o n e p erhaps within the colonnade above, wh ere the

ceiling coffe rs were also ca rved (a n ovel practice), and perh aps another around

the crown mg cha ri ot base. Free-stand ing statu es may go between columns and

perhaps on the roofbut th ere were free-sta n ding (or at least, carved in the rou n d)

n arrative grou ps which must have been set on deeper ledges around the podium,

hke a pediment but com posed as fri ezes. T h e sc ale of these ranges from lifcsize

to colossal, with one b1 g Sl,!ated figure , probably th e king, set p rominently some -

where, no doubt ccmre front. The chariot atop and the pyramidal roofsee m to

convey non-Greek, Ori ental intimations of immortality for the occupan ts, but

the sculp ture and ItS narranve are purely Greek, and rhe style is that ofthe home-

land, not East Greece like that created for Lycia, Caria's south-eastern neighbour

(Chapter Eleven).

The many fragments brought to London a rc n ow supplemented from n ew

excavations at 13udrum. Much of the fi-iezes was recovered from the Crusader-

th en-Turkish fo rt at the harbour. wh ere they had been set in the ,vaiJs, and then

used for target practice [240) . There are parts of th e colossal chariot horses and

lions [1 8.1,2] (certamly fro m the roof), the horses sp lendidly vital, th e hons rather

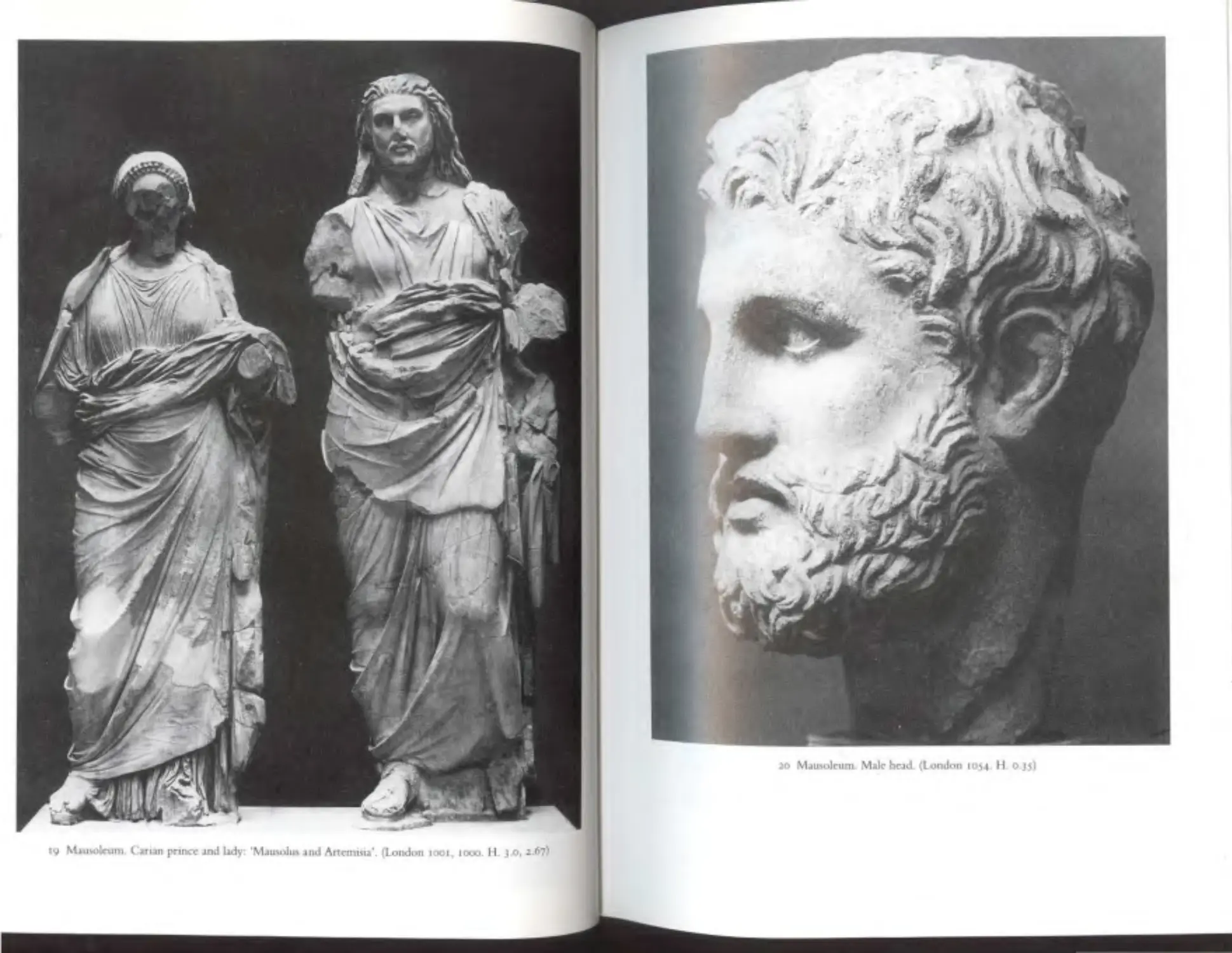

tame beasts. Can an nobility is represented in colossal fi gures of which the two

best preserved have mevitably become known as Mausolus and Artemisia [19).

He IS a fine characterization , not a portrait, ofa foreigner (in Greek terms, by a

Greek artist), Wi th lm wild mane o f hair and secret, rather smister expression.

Contrast the ve ry Greek h ead [2o). 'Artemi sia' obeys the gen eral anonymity o f

feature and expression ofall Greek female statuary of the period. The figures in

the round wh1ch were set in friezes show a fight of Persians a nd Greeks [18.J J,

though which Greeks is m oot, and we must rem ember that the monument was

bui lt in a city n ominally under Persian control.

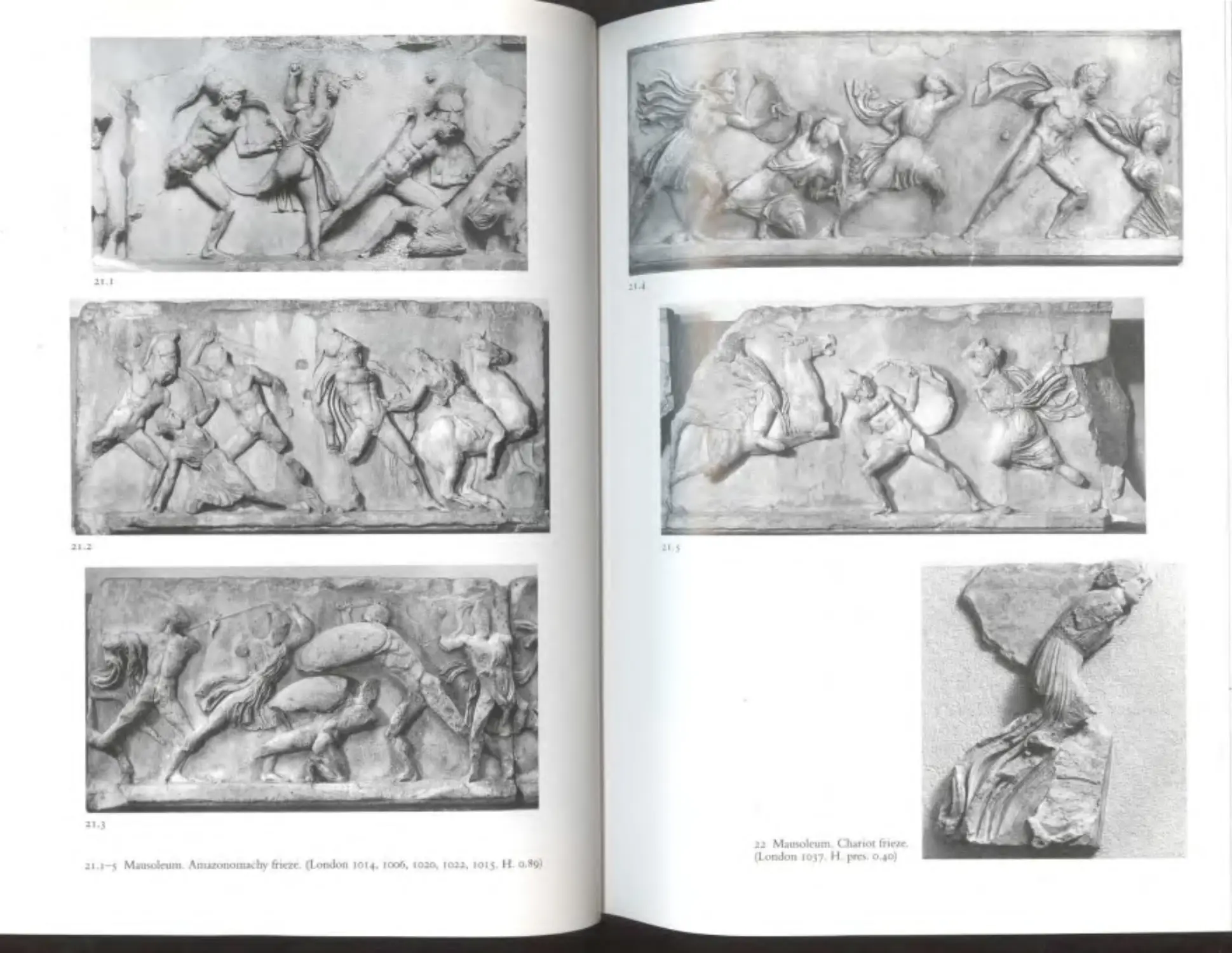

A more conve ntionally executed relief fr ieze has Greeks fi gh ting Amazons,

an other subject wh1ch elsewh ere in the Greek world seems to carry Greek v.

Persia n connotations. This is the version with both Heraclcs and Thcseus m

action. The frieze is composed in duels and threesomes, overlappi ng the slab

.

.

115

[2 1). The figures present ser ies of triangular and oblique schem es which

J01 the narrative without appearmg repetmve, and mdccd, to a v1ewer In

cartYd pnvileged with a closer view than \vaS poss ible m annqmty, conveymg

~ 00·

.

b

f

(,fexcited annciparion of the flow of battle. There are none etter o

degree

·

.

.

ah Cb<wal peri od. Individual figures present standard poses, the lungmg, col-

t e d t\"lstmg back-turned but all. executed w nh a n ew and controlled

I<C

•.

,

•

ap.

' The fim~tes are well spaced with less use of the flymg dress to fill the

P

assJOn.

,.

round (c : [5 .1 J, GSCP fig. 1 27). The Amazons , some n ea r-naked, arc thrcat-

g.

•-et wholly femi nine; the Greeks, It seems, desperate. Acnon scenes m

~~1

.

d

G k sculpture are rarely so movm g, ye t these are figures wh1ch also eserve

1re: in<-•v •dual attention, for expreSSion of derail in features and anatomy.

~~~ther 1o less expressive fi- ieze sh ows cha n ots: [22] Wi th a Carian driver.

Pythc ,5 and Satyros wrote a book abou t the Mausoleum. They were proba-

bly arch;tect/ sculptors, since Pliny says that one Pythis mad e the c hariot group,

robab lv meaning Pyrheos, and Satyros sign ed a base at Dclph1 for statues of

~ausol~< successors. Pl iny an d Vitruvius record the tradition that th e sc ulptures

were the wo rk of fa m ous homeland Greek artists: Lc ochares, Bryax is, Scopas,

Timoth eos and (Vitruvius o nl y) Praxi tel es. The impli cation is that each artist

worked on one si d e of the monument. Scholars have in ev itably attempted to

apportion the survivi n g sculptures, without agree me nt o n any single name or

style. T ht ancient attribution may contain a morsel of truth, but there may be

hardly mo re to the story than can be gleaned from that about the competition

fo rthe Amazons at Eph esus (GSCP 213f.) . Site guides o f antiquity in Asia Minor

may ha•· been as free in rl1 ei r use of great names as many a site guide is today,

bur the•e was litcramre about the buildi ng, consulted by both Vitruvius and

Plmy, ne d oubt, and we can be su re that a maJOr artist (Pyth eos?) o r artists from

Greece c ntrolled the design and execution of the sculpture, even if we ca nnot

name hu• o r them. The fact that th e named arusts executed oth er works in Caria

or nearb may be taken either to support the story of th eir work on the

Mausol eu m, or explain it.

The Mausoleum was o n e ofthe Seven Wonders of the anCie nt world; so was

our nex. subject. The Temple ofArtemis at Ephcsus, o ne ofthe largest and most

ornate of the great Archaic Ionian structures (GSAP 16of.), 'vas burnt to the

ground 356. R ebuildin g was soon in hand, sin ce, when Alexander passed, he

offered o help but was politely turned down ('a god should not make offer ings

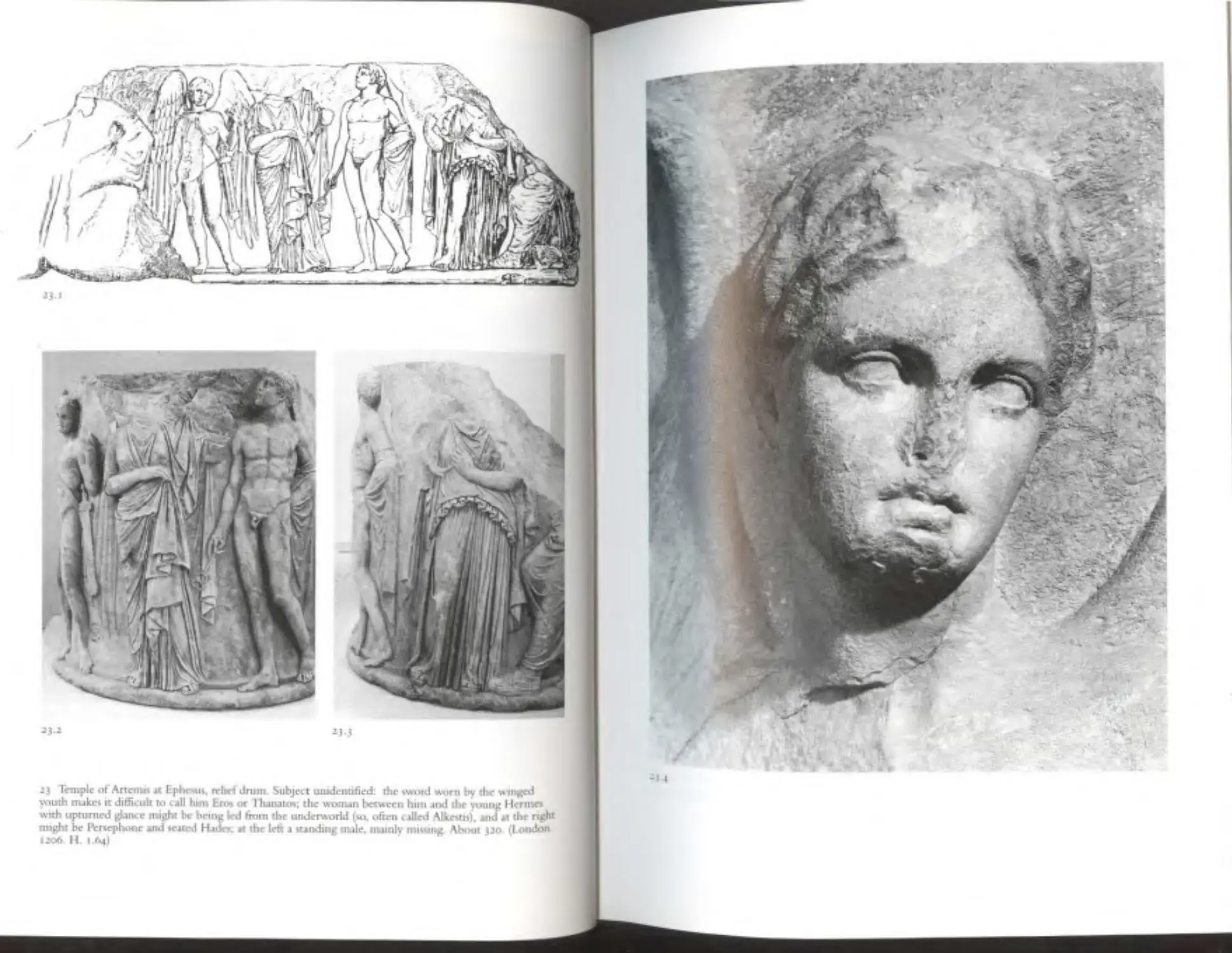

to anotl er god'!). One of the rel ief-d ecorated columns (co /wmwe caelatae) \vaS

<aid to nave been carved by Scopas. The principal remain ing relief sc ulpture

whi ch see ms fourth -century is from rectangular column pedestals , and !Tom

drums which were probably set at the tops of the columns; in oth er words, the

Arch aic schem e was p robably retained. R eliefsculpture in the upperworks ofthe

templ e s later (the building \vas said to have taken 120 years to compl ete) but it

looks thou gh th e decorated colu mns were m position by about 320. Their

subJect• are puzzling, even the best preserved [23] which seems to have unex-

29

pected underworld conn otations. There are two Heracl eses, fights, Nereids 011

hippocamps, Victories wtth animal offe rings, groups o f men (incl uding some

Persian, trousered) and wom en. The carving is of high qualiry, the srylc m some

respects very o ld-fashJOned but there is not much to compare at th1s date, o r

indeed earlier, for large nar rative groups {the fi gu res are li fes ize), and the figures

most resemble th e best o n Athenian grave re liefS.

The c1ry of Pnene on the coast south ofEphesus was a new foundanon ofthe

fourth century. Whether tt was founded by the Carian kings (H ekatomn1ds) 10

the nud-fourth century, o r by Alexander later, will naturally affect our view of

the date ofth e sculpture for 1ts Temple ofAthena Polias. Th1s has generall y been

thought H ellenistic and it is difficult to place it earli er, thou gh a recent study has

detected similarities to the Mausoleum. The gen eral appearance of the re mams

certaml y suggem so mething quite advanced, anticipating 111 mood and su bJect,

if not detail o f style, the Great Altar at Perga mum (HS fi gs. 193-9). Tiny bits of

the acrolithic cult statue were found, an d th e re li ef figures from an altar, which

is certai nly later. The early rel ief fragm e nts prove to b e from ce1lt ng coffers ove r

th e temple. pe ri srylc (a lso a feature of the Mausoleum): twenty-six of them

sh owing episod es in the Gigamomachy (HS fig.202) including perhap s fou r

involving Amazo ns.

In the fifth century the subject matter of the architectural sc ulpture of the

great n ew build1ngs ofAthens proves a tantalizing challen ge to th ose who w1sh,

correctly, to determine wh at their message might have been (GSCP eh. 12). An

impress ion that the fou rth cenn1ry was less subtle may simply re fl ect our igno-

rance or lack ofimagination, but fo r the most part the record seems to offe r fewer

challenges. No single theme n eed carry the sa me message everywhere, o f course.

and th e Periclean Amazonomachies of Athens meant somethi ng far different

fro m th ose at Bassae, Argos, Delphi, or on the Mausoleum. We must bel ieve that

th roughout the C lassica l penod the designer's intentions, regardless of w hoever

had mstructed or adv1sed him, were understood by viewers when the work was

first unveiled, or that if th ere was any misunderstanding it \vas the resu lt of

dimm1shcd imcl lt gence or knowledge. The creation ofa building and ItS sculp-

ture took a long time, and in a small communiry of citizens, many of whom

might have been uwo lved in the work, knowledge of what was gomg on and

what \vas intended m u st have been fa irly general and probably detailed, requir-

ing n o commentary. Thereafter responses could vary and the origi nal message

easil y become lost once th e circumstances occasionin g the original d esign had

changed. I low, I wonder, did th e defeated Ath enian of 404 understand the

Parth enon sculptures created over thirry yea rs before in a spirit o f imperial pride

an d d efian ce? O r an Athenian of the mid-fourth ce ntury whose natural foe had

become th e Ma ced onian rather tha n the Persia n ' Did he, ind eed, speculate at

all? Much of th e scul pture was barely visible, certai nly not in the detail which

we require when we try to interp ret it and rea d its orig inal message. It seems

almost as though its function was as much as anything simply to be there, as

30

1a part of the house ofthe god as m roof or columns, and not even

1nt egradan lv as a visual primer for the worshi pper or p asserby. To say that it was

"'

011

'

h

Id

11d

.

to delight the gods w o cou sec a , an not man, 1s crude, butcomes

d

1

•ere More· truly it reflects th e craftsman's desire that his work for such a

c ose.

rfi

I·

·

h

·

f

I

11

Ose <hould be pe ect, tr tiOII, carrymg t e nonon o comp eteness as we as

purp··

perfecuon.

Greeks were essentially practical people an d would have m ade readily visible

hat""' mea nt to be seen and srud1ed. The1r msc ribed decrees are a compara-

~le case. barely legible even to the few lnerate (with no word division and vir-

tuallY no pun ctuation), but important as matenal testimony to things done or

agreed . T he role of th e decorat ion on tem ples changed only when the sc ul p-

tures them<elves became pnzed as art- ObJeCtS to be imitated or copied or stolen,

or when the monument became a tourist attraction. At that point we turn to

Pausanias, author ofthe second-centu ry AD GUtde to Greece, for comment, and

find that at best he recorded th e mytho logy; an d that h e ignored the Parthenon

fr ieze co mp letely. Fourth-century Athenians, at least, we re prouclly consciou s of

the ciry 's historical and myth-historical achievem ents in so fa r as their orators

provided ready eulogies on the subject , but were they as conscious ofthe subtle

messages of the monuments that had been bu ilt to celebrate th em? The orators

seem often to h ave picked on ep isodes generally 1gn orcd in art, at any rate. We

probably do wrong tO assu me that the Greeks shared our devotion to such

matters, att d their antiquarian interests seem to have been quite differently

motivated.

We need also to consider the sc ulpture as pa rt of the architecture and in n o

small degree determined by it. Tlm is an approach whi ch this small book cannot

easily ahu undertake but it should b e 111 the mmds ofthose who view the more

complete asse mblages of scu lptu re 111 reconstructio ns o r o n models of whole

buildings. Thus, the acroterial sculpture \vas th e most distant yet m ost promi-

nent bemg silhouetted aga inst the sky; the pediments were poised over equal-

spaced weight-bearing colu mns wh1 ch nught have played their part in the overall

des•gn of the sculpture groups above them. The narrative m essages ofhigh fri ezes

needed to be simple ifmtended to be understood o r to contribute som ething to

the effectiveness of the temple. That they could not be understood in detail I

have pointed out already, and the impli cations of this fo r ' m essages', bur there

was an absolute need to observe standard formu lae of narrative in their d esign.

Tothis d eg ree th e art o f sculpture is also an archi tectural art; it requires recog-

llltton as such , an d we h ave seen how important a role architects migh t have

played al so 111 sculptural d esign .

3I

4·'

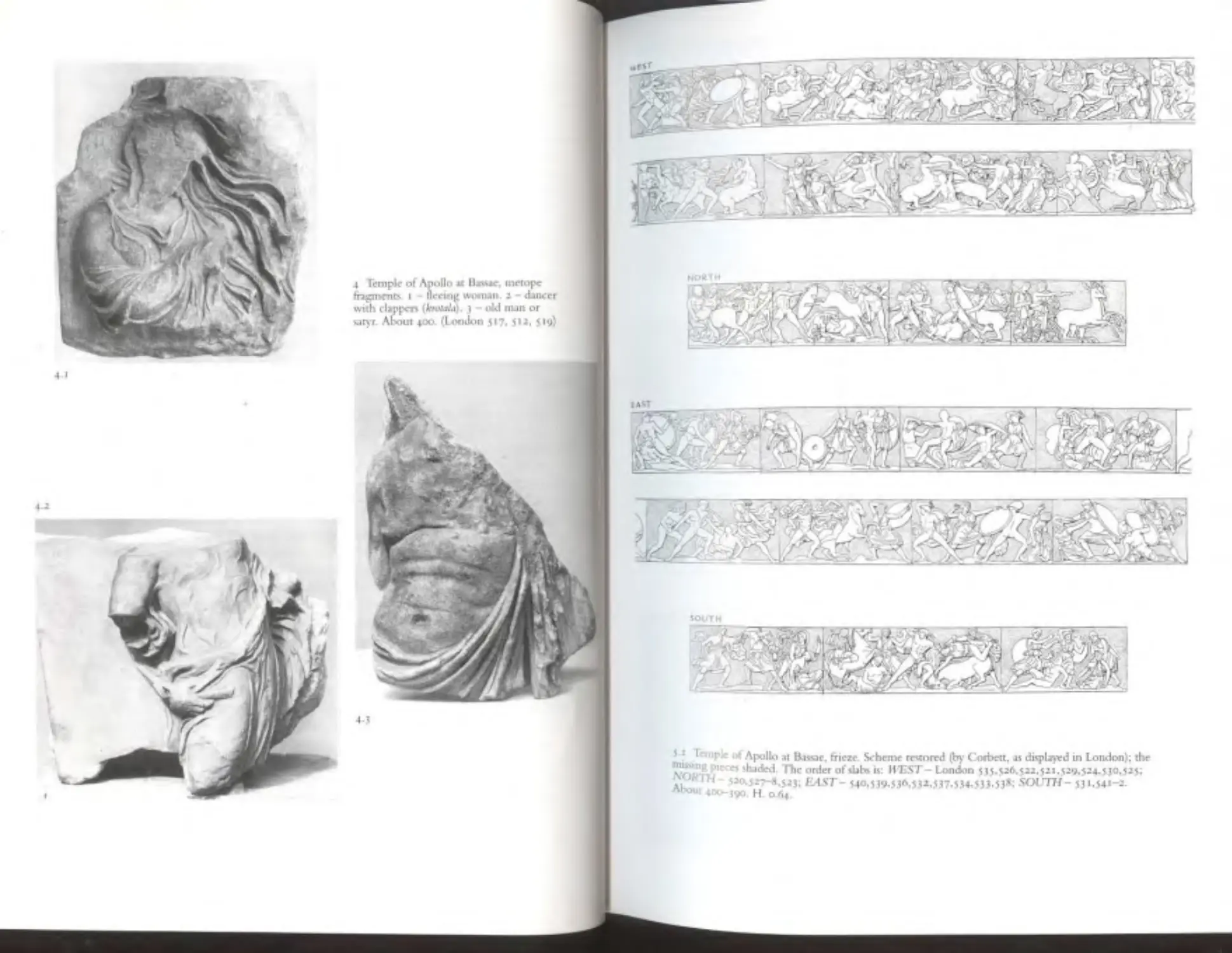

4 Temple of Apollo at Ua\UC, metopc

fr.agme nts. 1 Oeemg wornan. 2 - dancer

with clappers (kr<JMia). ] -old nun or

satyr. Abou1 400. (London 517,512, 5 19)

4·3

l·1

'Temple ofApollo aJ Bame, fneze . Sch eme rc\tored (by Corbett, as displayed in London); the

'Z~ng pteces \haded. The order of slabs 1s: ~ VEST - London SJS,S26,szz,szt,529,524,530,525;

A~RTH 520.\27- 8,523; F.AST 540,5J9 ,5J6,5Jl ,5J7, SJ4.SJJ ,SJ8; SOUTH- SJ 1,541-1.

Ut 40C>-_l90. H 0.6.

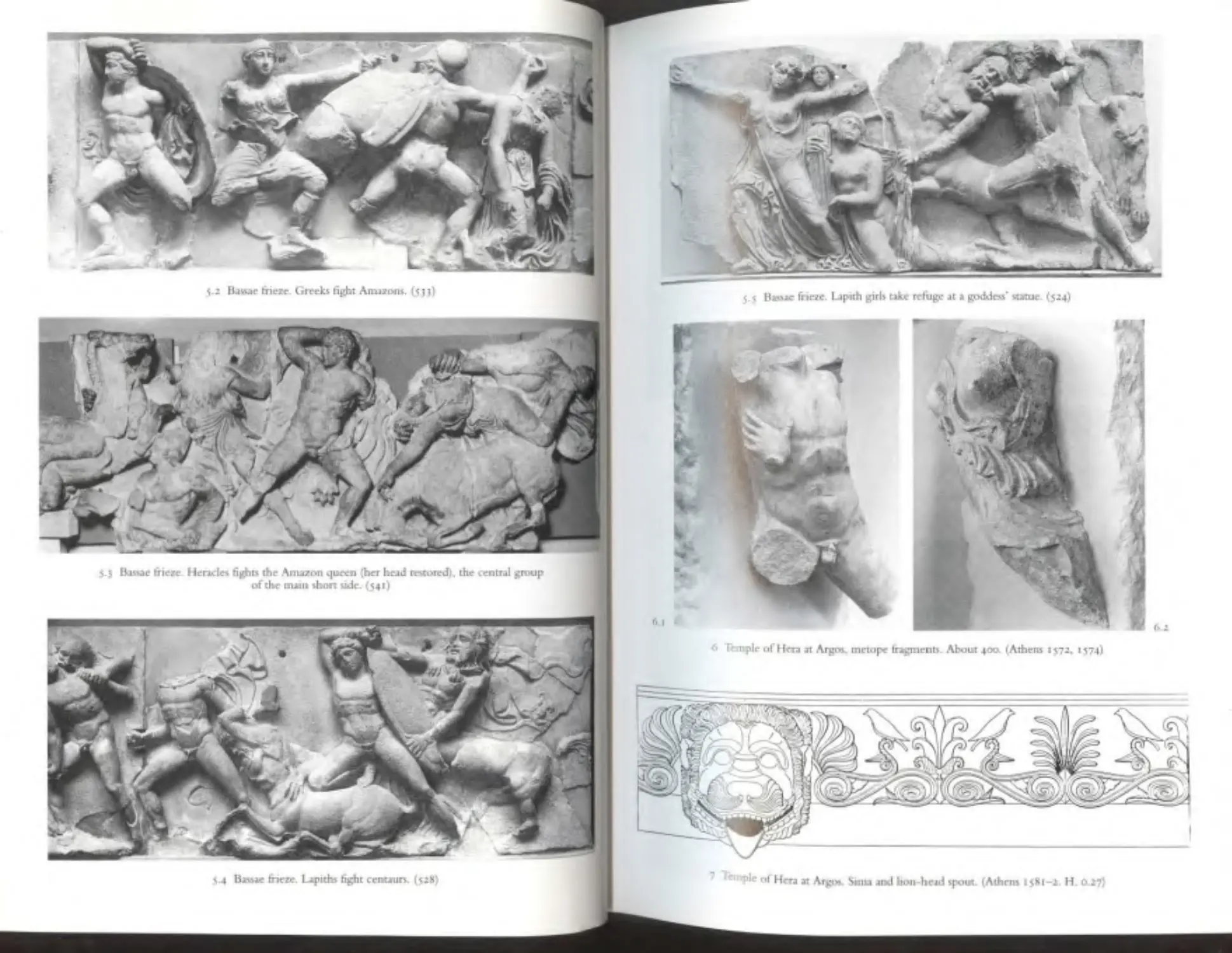

5.2 DlS.Sle fneze. Greeks fight Anuzoru. (533)

S-3 Utluae li-1eu. H endes fights the Amazon queen (her h~d restored), the centnl group

ofthe m~m short stde. (5 41 )

5.4 BN>< froeze. l>potru fight cenuun. (s>8)

''-I

5-5 B~e fneze. Lap1th g n h take refuge tlt a goddess' ~ucue. (524)

6 Temple of Hen at Argos. metope fngmenb.. About 400. (At hens 1572, 1574)

7 1: •plr of Hen at Argos. Sinu 1-nd bon. hetld spout. (Athens 158 1-2. H . 0 .27)

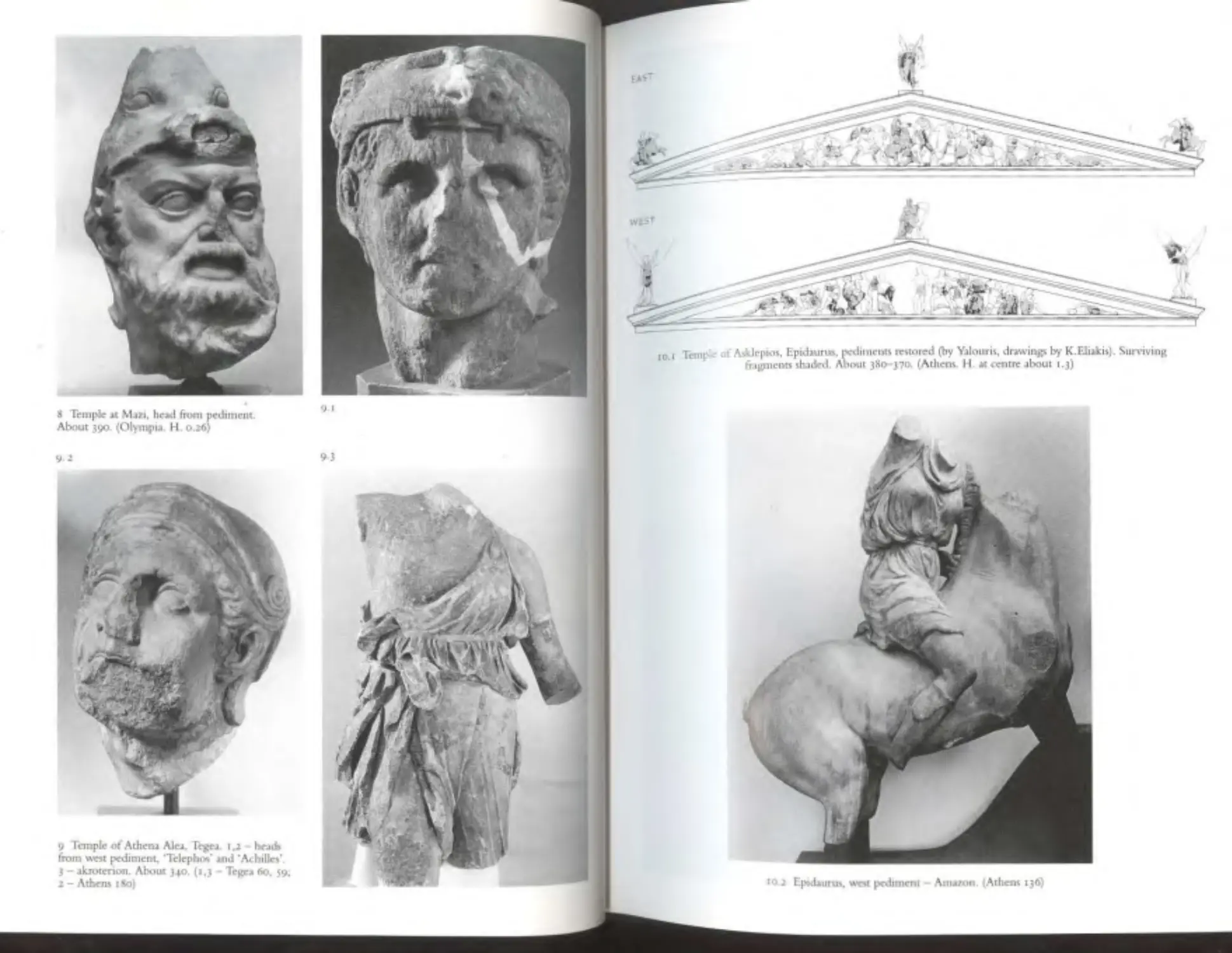

8 Temple :u Maz1, head from pednnent.

About 390. (Olympoa H. 0.26)

9 Temple ofAthen• Ale., Tege> t,l he.ds

from west ped1ment, 'Tclephos' ;and 'AchtUn'

3- akrot<non. About 340. (t,3 Tege• 6o, 59;

2 - Athens tl!o)

9·3

Temple ofAsklepim, Ep1daurus, pednncms restored (by Yalour is, dr..winbi"S by K.Eliakis). Su rviving

fnbrrtlents shaded. About J8G-)70. (Ath ens. H . at cen tre about 1.3)

10.2 Ep1daurus, " -'CSt pediment- Amazon (Athens 136)

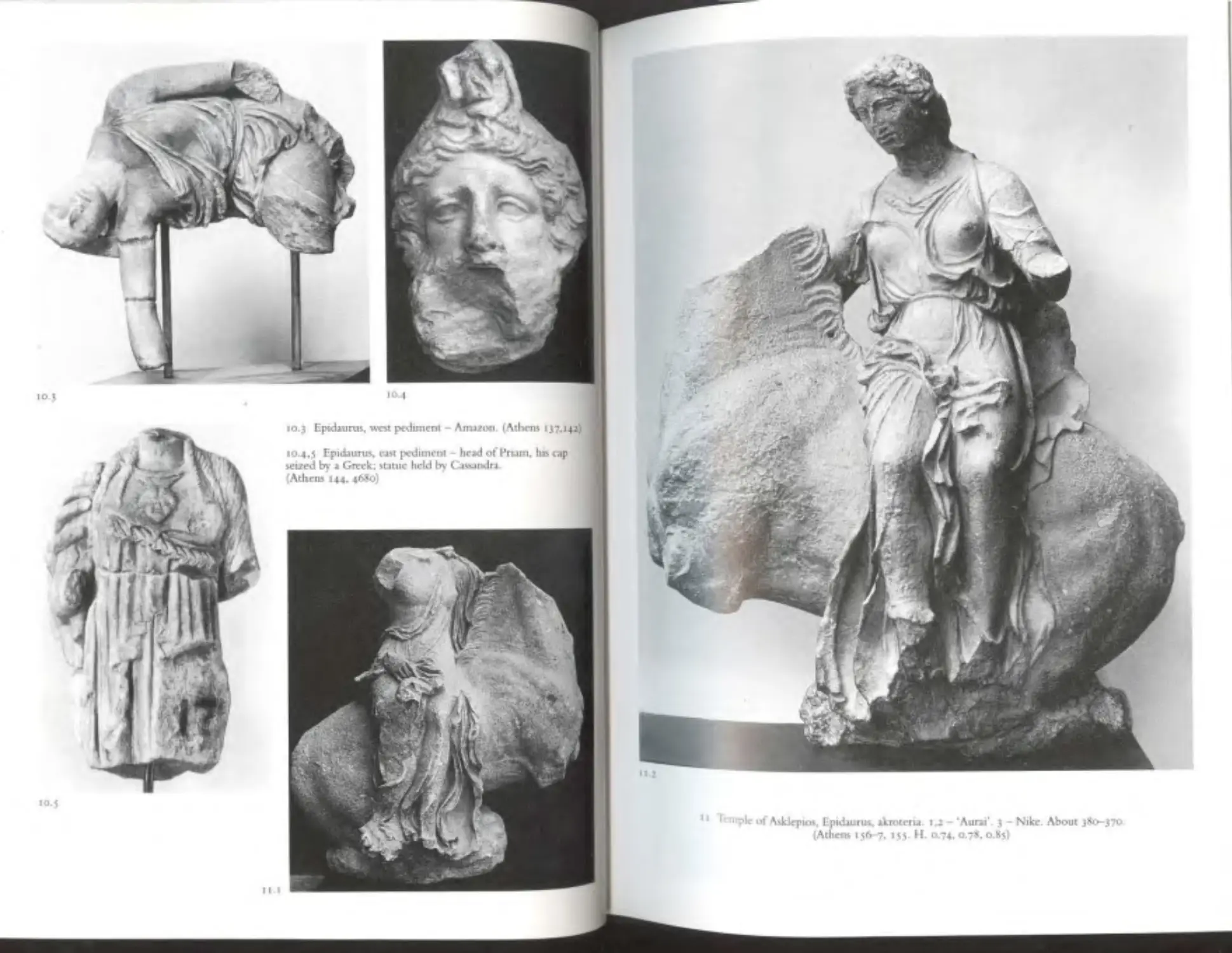

IO.J

1o.s

11.1

10.3 Epic:burus. west pedtment - Amazon. {Athens IJ7, 14l)

10.4 .5 Epidauru.s. east pednncnt head of Pnam, hlS cap

sc12ed by a GTC"ek; stuue held by C:~~wndr::a

(Athens 144. 468 o)

11 Temple ofA•kleptos. Eptdaurus. •krot eri• t .2- 'Aunt ' , 3 - Ntke. About 38<>-J 70 .

(Athens •se>-?. t 5l. ll . 0 .74. o.7H. o .85)

I 1.)

12 Akroterion {or Andromeda?).

About 380. (London. Royal Academy)

IJ J>elpht, Marm:an a. mecopcs. 1 man 1nd hof'\e. l .J -

figum from AnuzonomJt:hy. About 380. (Ddplu. H . o .62 5)

1].1

IJ.l

13·3

14 le nple of Apollo at Delph1, ped1ments. 1 Thy1ad. 2 - Kttharodc {the head not certainly

belongtng). About 33<>-JlO. (Delpln T l l 6, 1344+2380; drawing by K .Eli•kis)

ll Udpha. Ac>nlhus Column. Abou1 JJO. (Ddpha. H. of6gur<S 1.91)

16 Atherti. Lyucnte\ monum~nt frieze. Dtony,cx

wnh ~tyn punishmg the ptnte~ whom the goJ t$

tur nmg mto dolphtn'. Dn'",ng ~nd c.1sts. For \•tctory

m B4· (Athens. C'.l\U m London. 11 0.2SS)

q.2

17 The Mausoleum at Haltk:anussos.

n:coru:trucrions. 36<r350.

(1 - G.W>ywell/S.Bud. 2 - K .Jeppcscn)

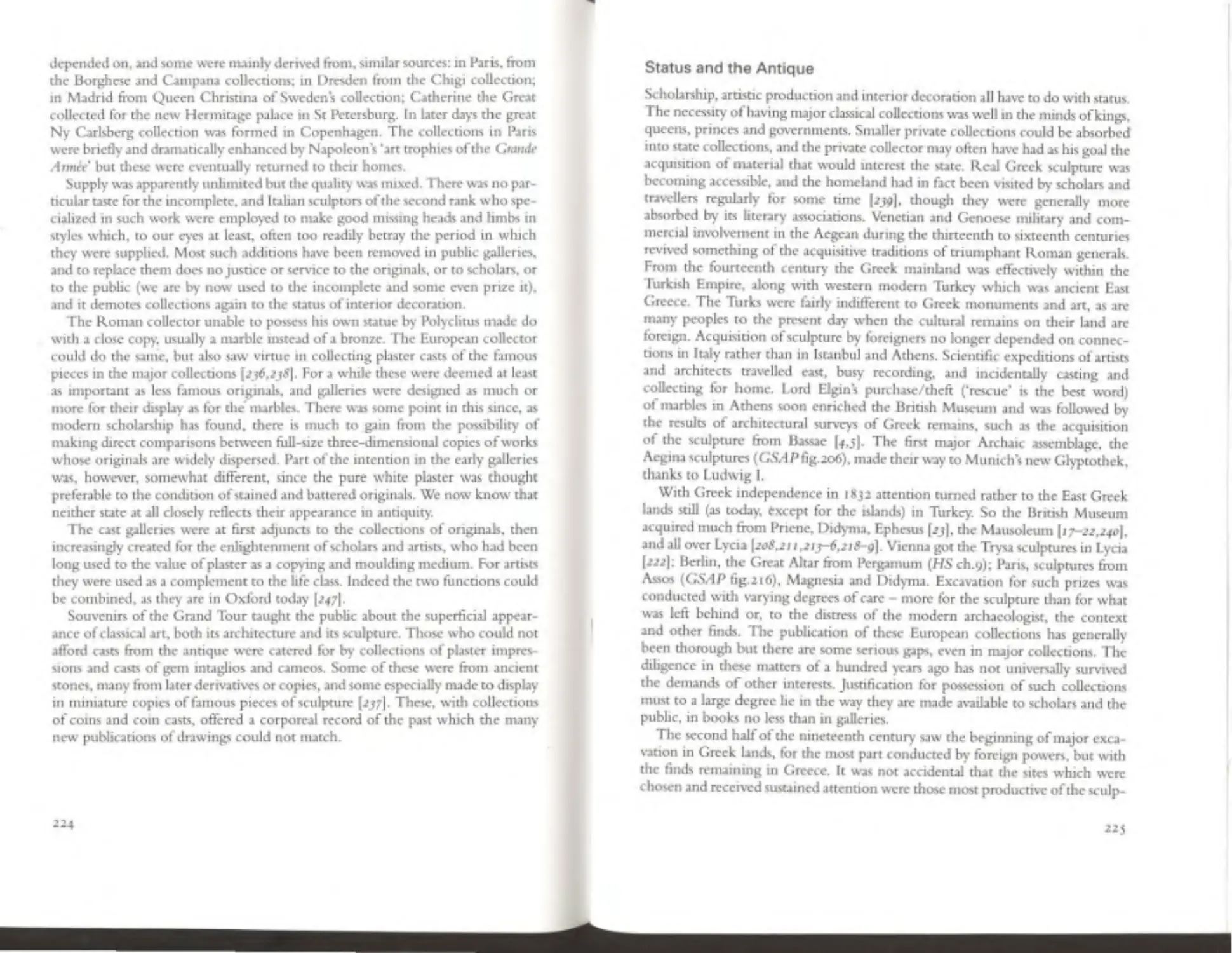

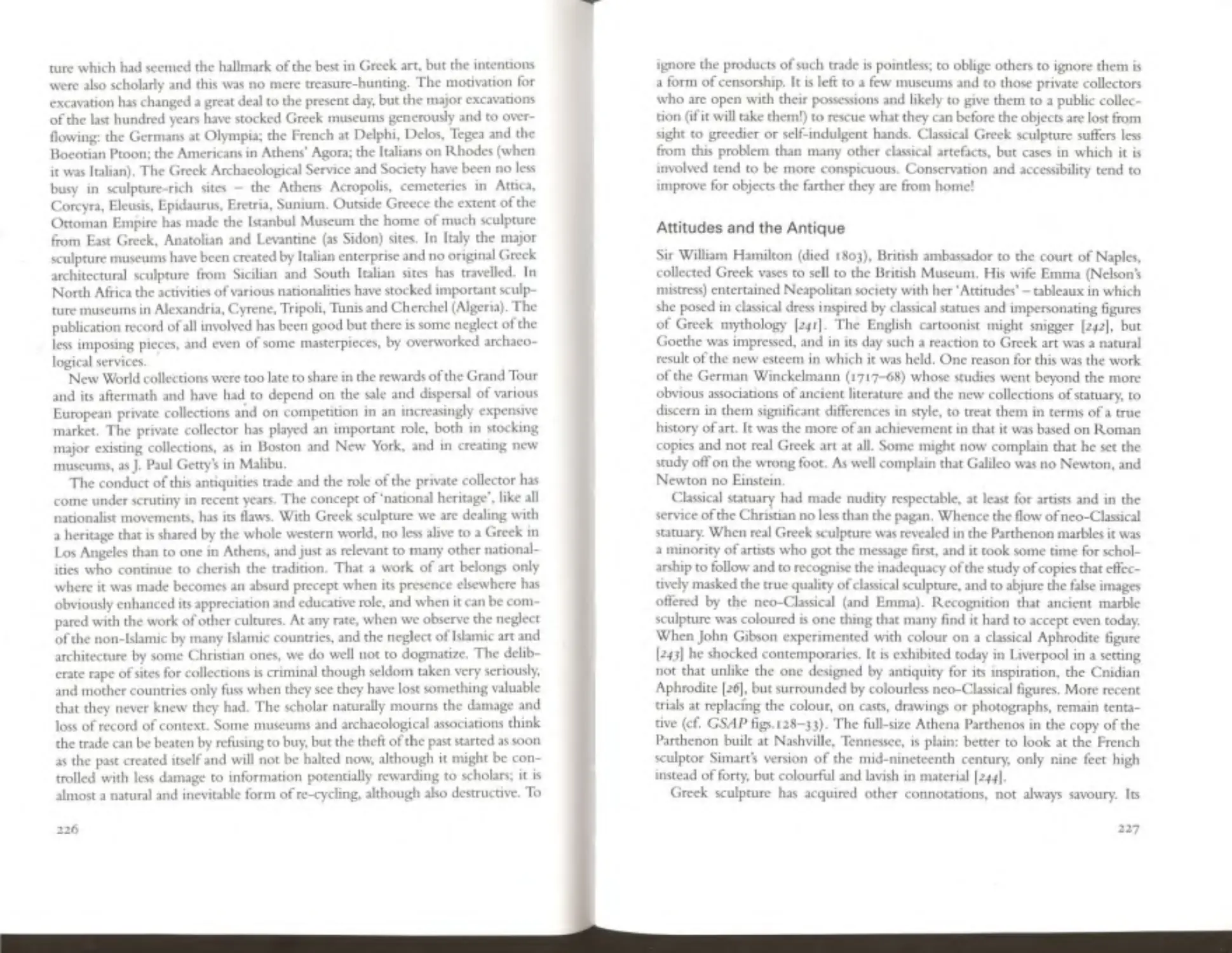

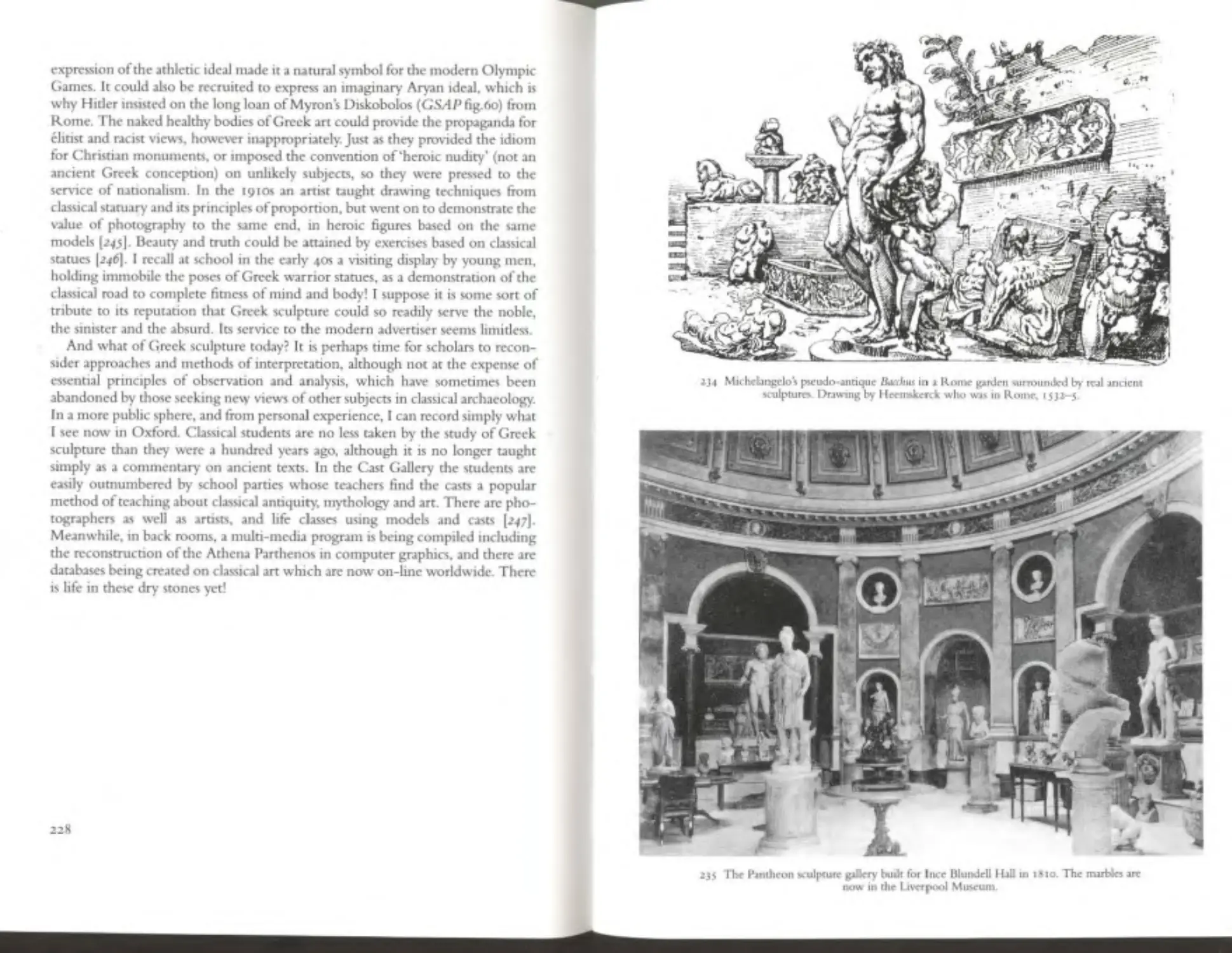

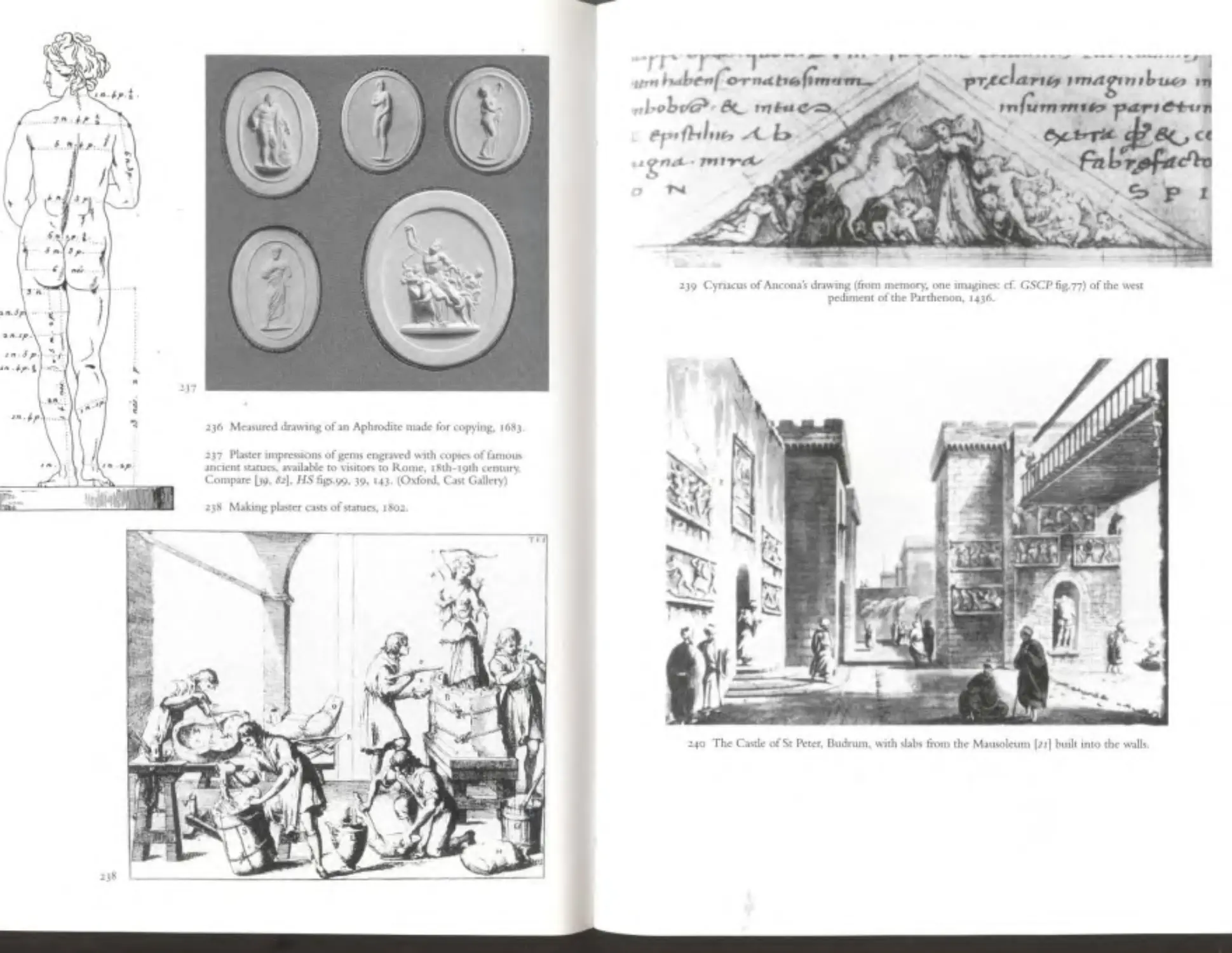

18 Mausoleum. 1 - horse from chariot

group. 2 - hon 3 - mounted Persian

(London 1002, 1075. IO.JS 11 2.JJ ,

1.5, L. 2.15)

1~.1

20 Mausoleum. Male head. (London 1054, H O.JS)

19 Mau~lcum. Un:an prince and IJ.dy: 'M:ausolus and Artenus1a'. (London 1001. 1000. H . J .O, 2.67)

!Ll

21.3

21 1-5 M;m~l~um. Amuononuchy fr1~u. (London 1014, 1oo6. 101:0, 10::. 1015. 1f . o.89)

!I.S

1:1 Mau«)l~um . Ch;mot fn~ZC'.

(London 10]7. 11 . P"'' 0.40)

lJ.I

23.2

2J.J

23 Temple ofArtcnm at fphe\m, ~hef dnun. Subject urudenufied: the sword \\·orn by the w1nged

youth m;~ke') H d•ffic.:ult to coall lmn Eros or I lunatos; the woman bet\veen him and the young Henne\

with upturned glance Jlllght be bemg led from the underworld (so. often nUed Alk~us), ;and oat the n~ht

rmght be Pcrsephone ;and seoated H;ul('); at the lefi ;a sundmg malt. num]y nm~mg. About 320. (London

I200. H I.64)

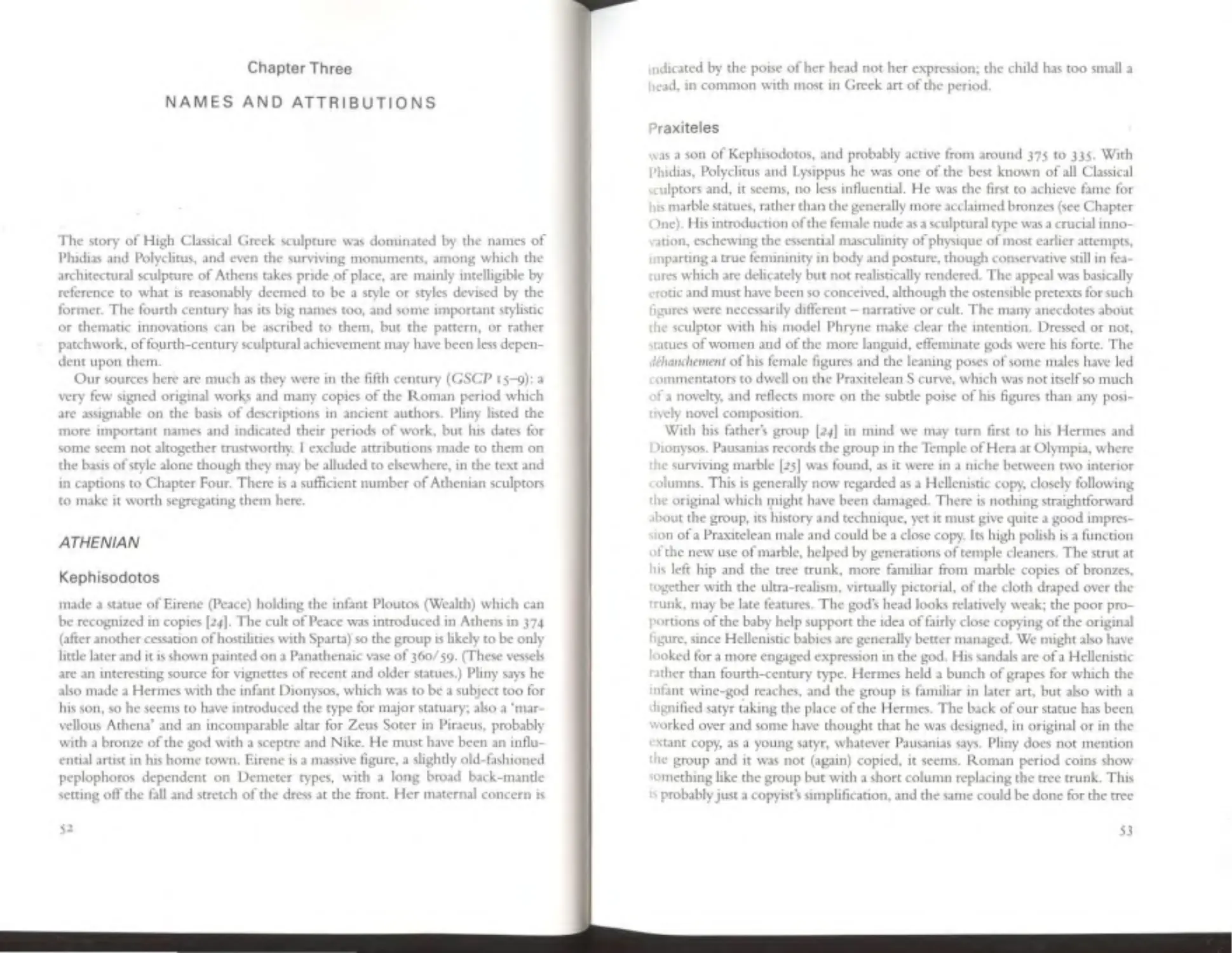

Chapter Three

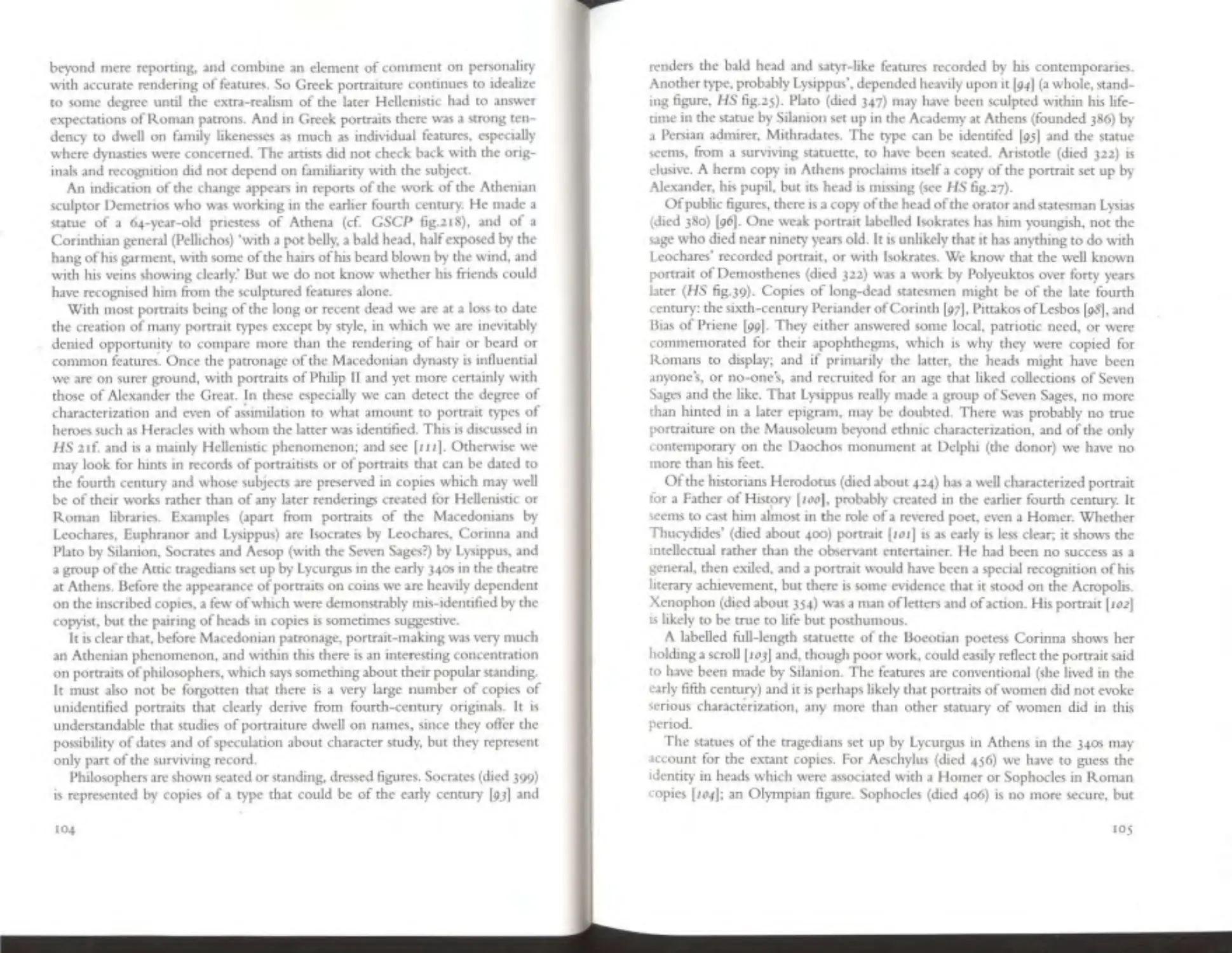

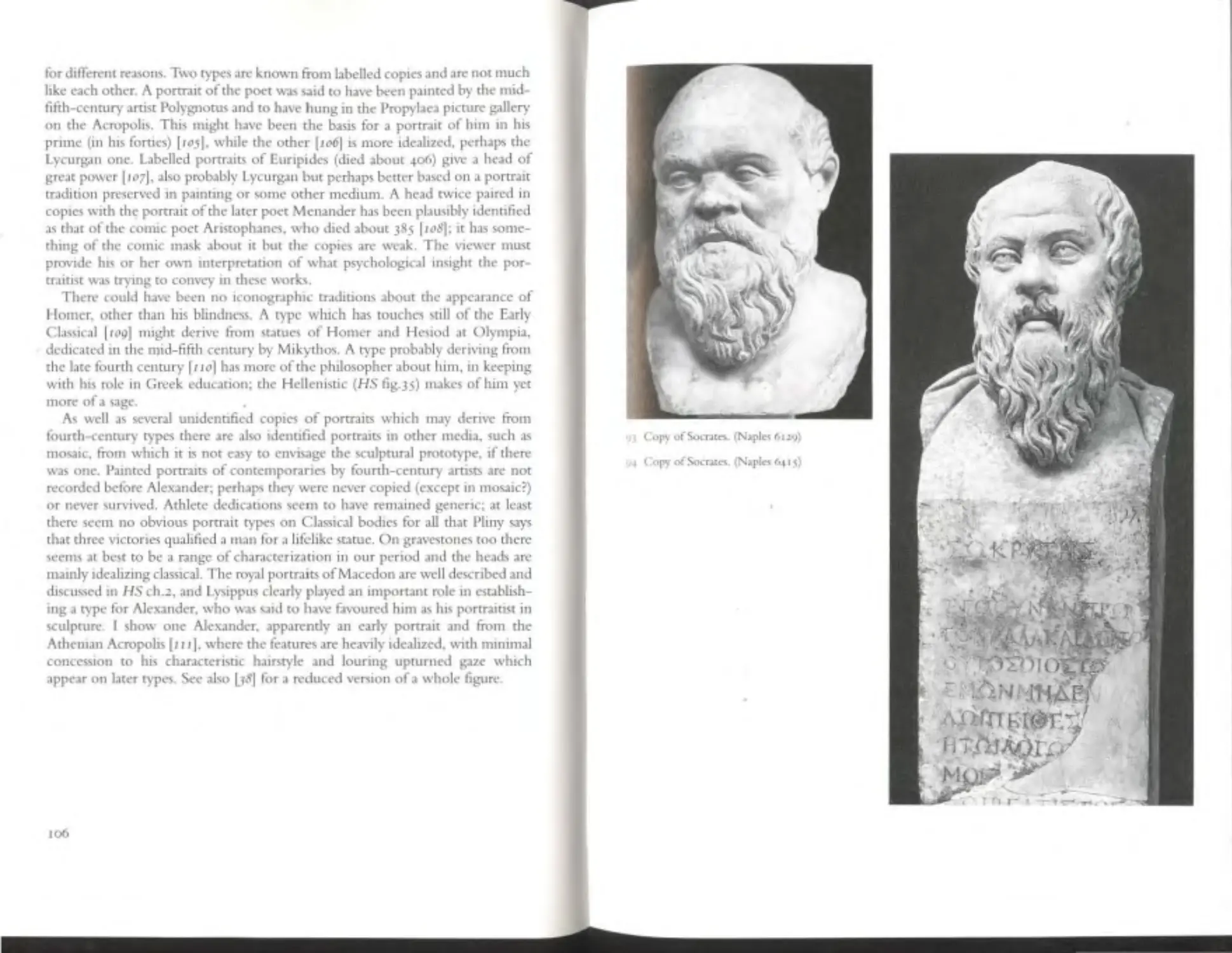

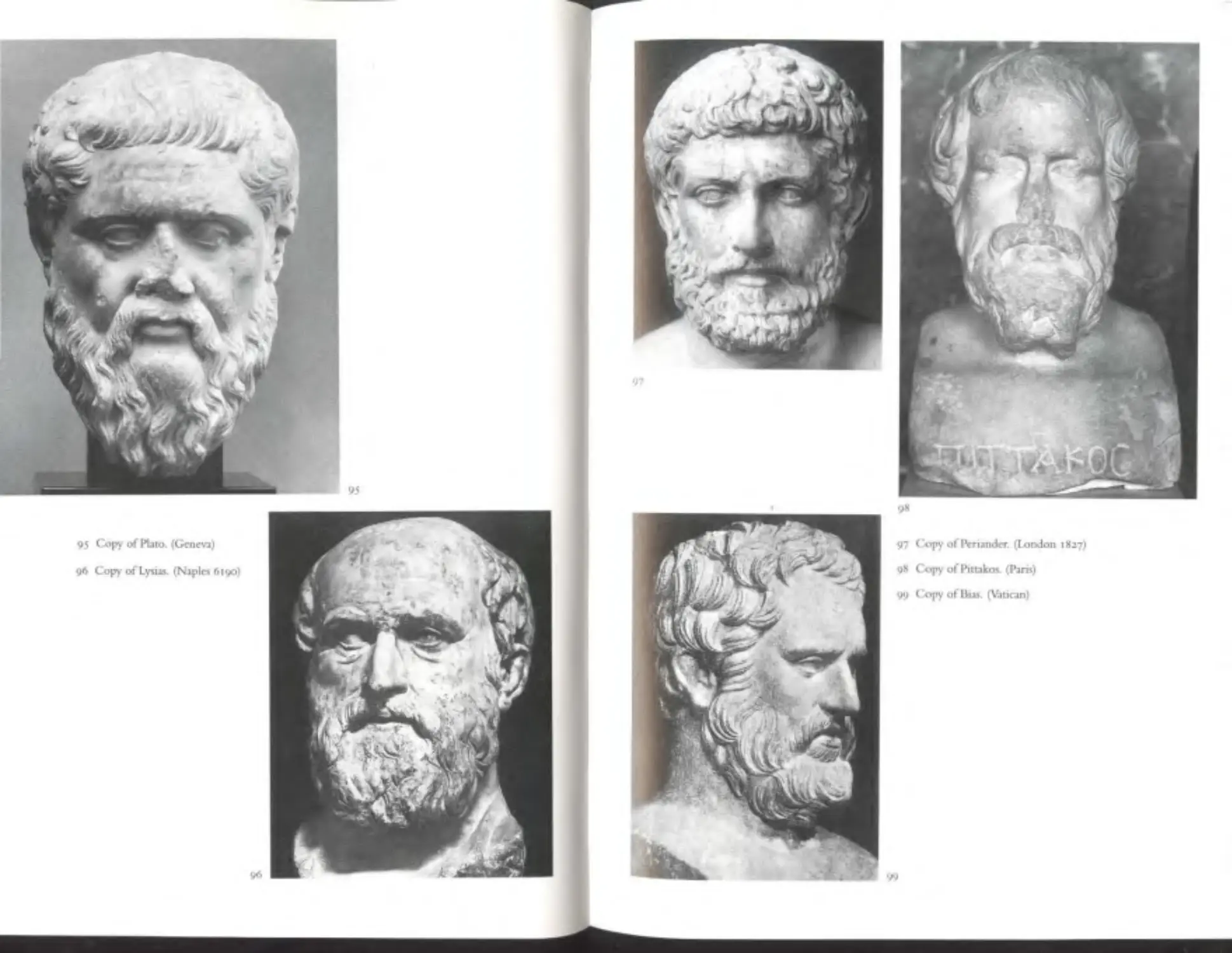

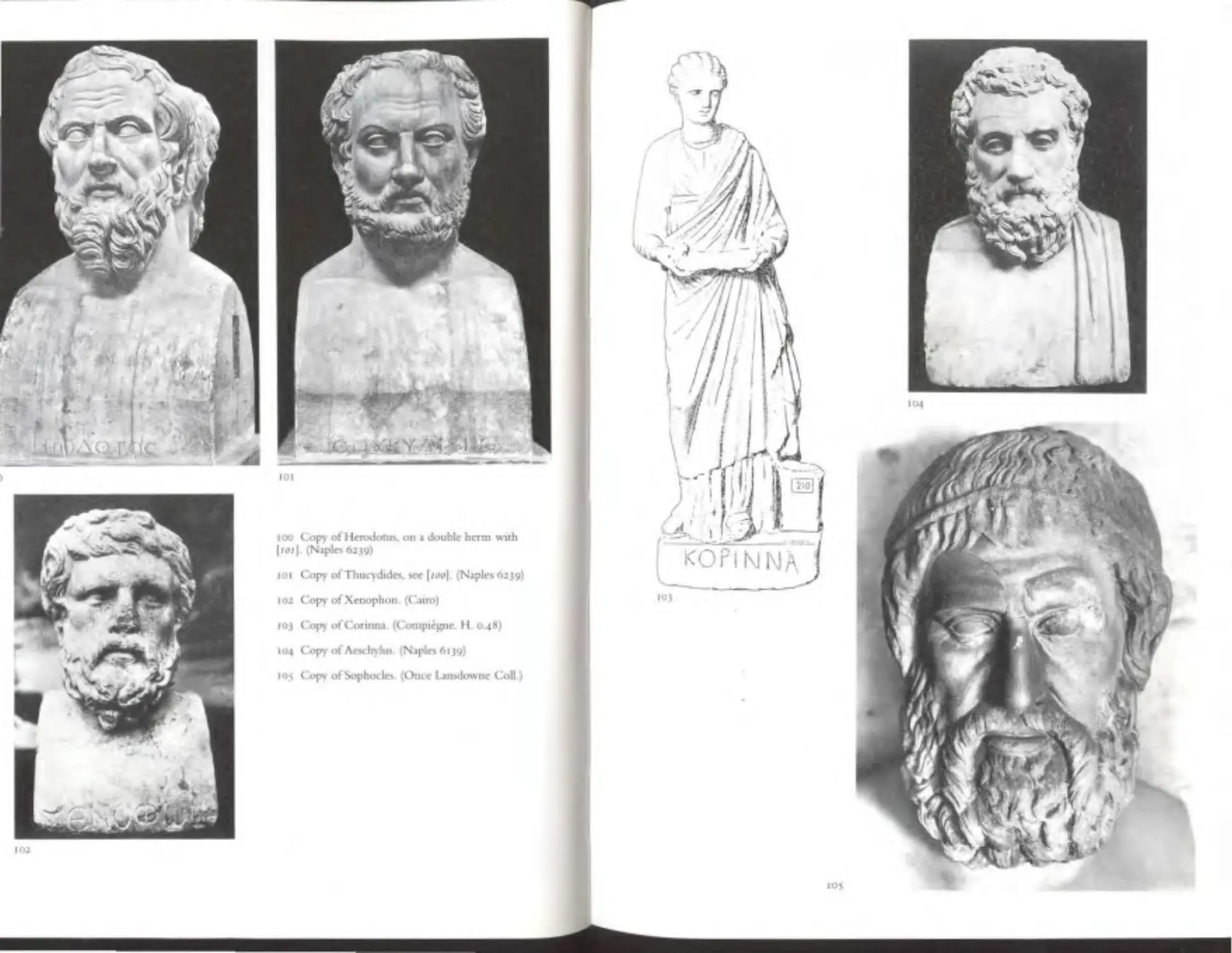

NAMES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

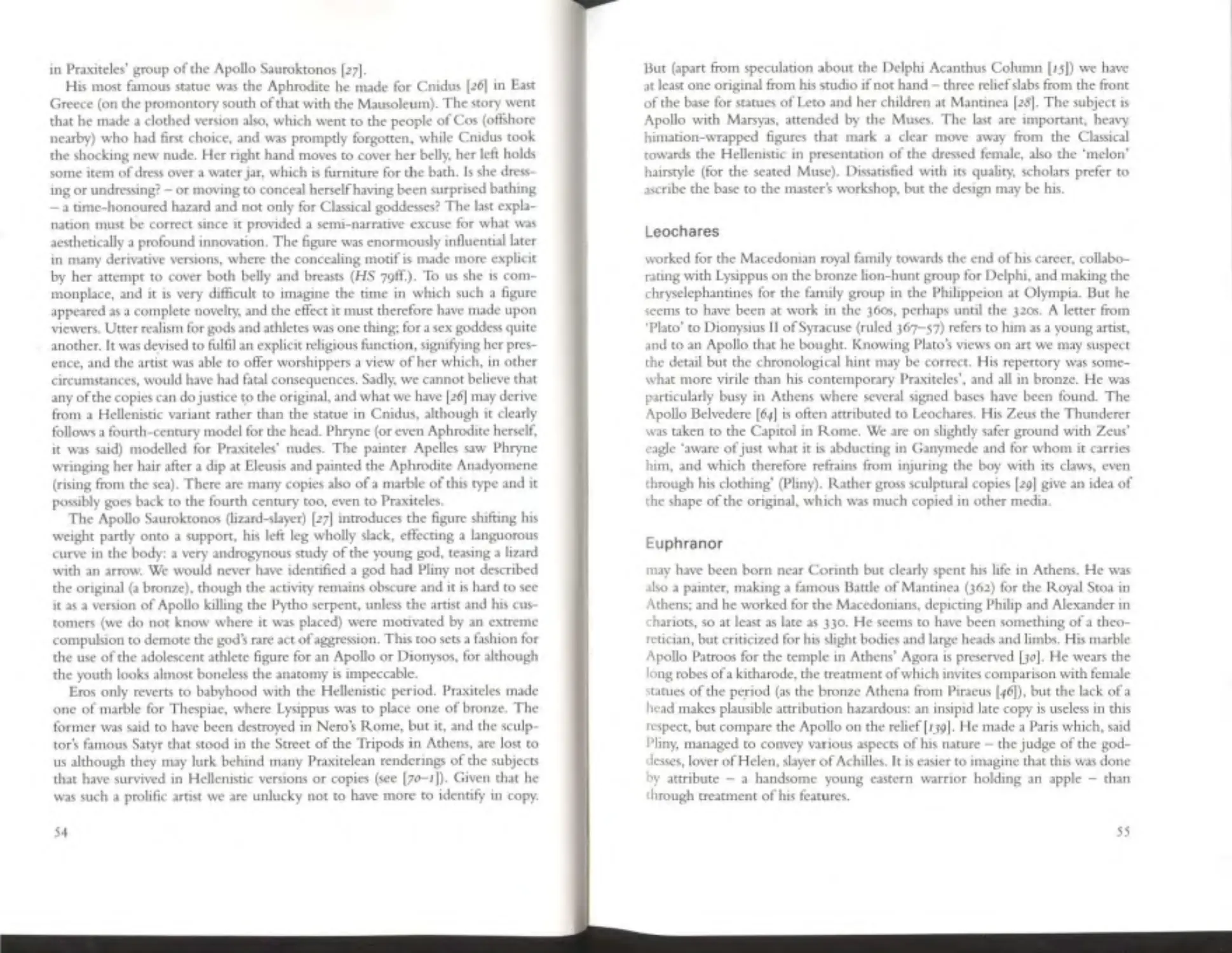

The story of High Classical Greek sculpture was donnnated by the names of

Phid1as and Polyclirus, and even the surviVI ng monuments, among which the

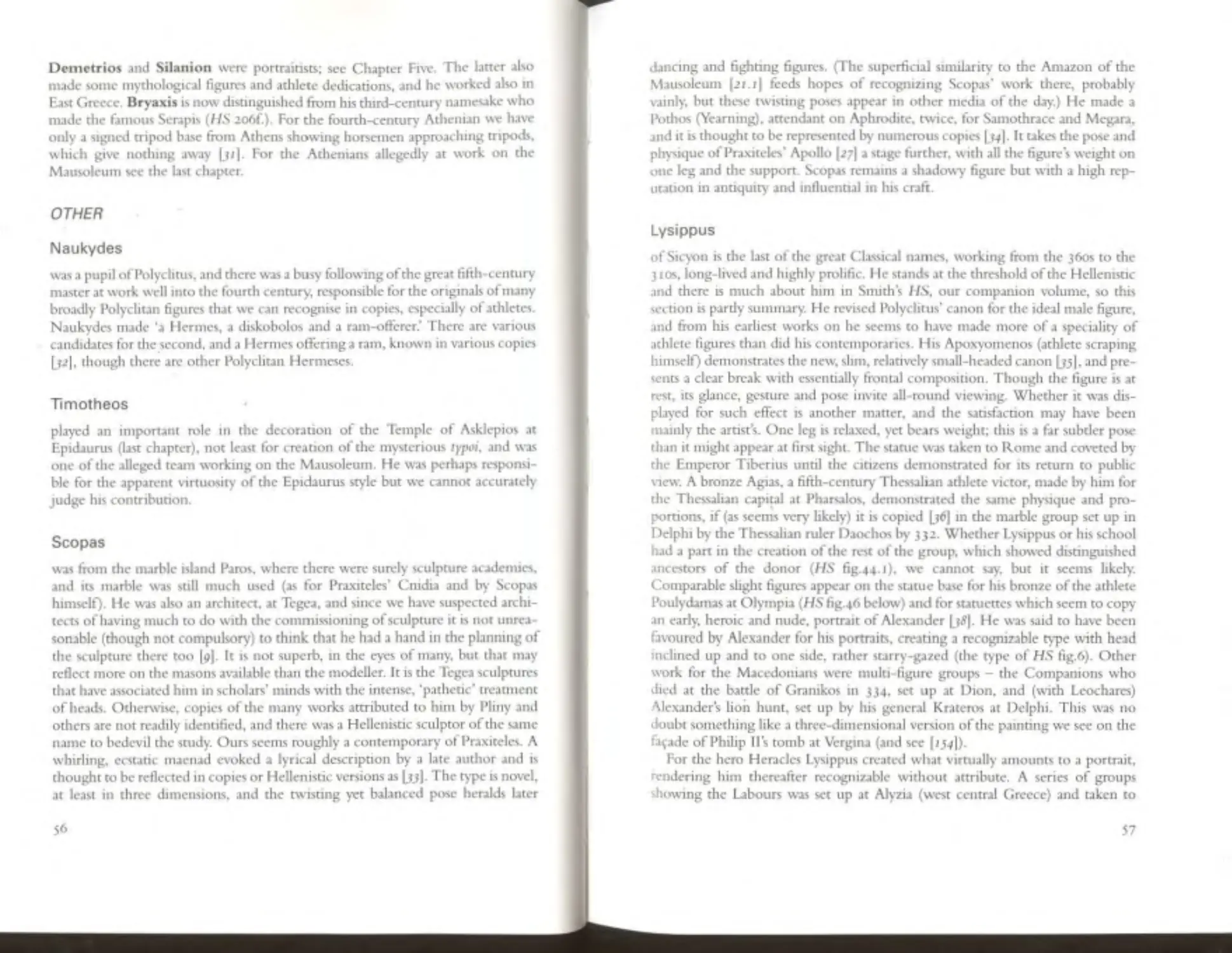

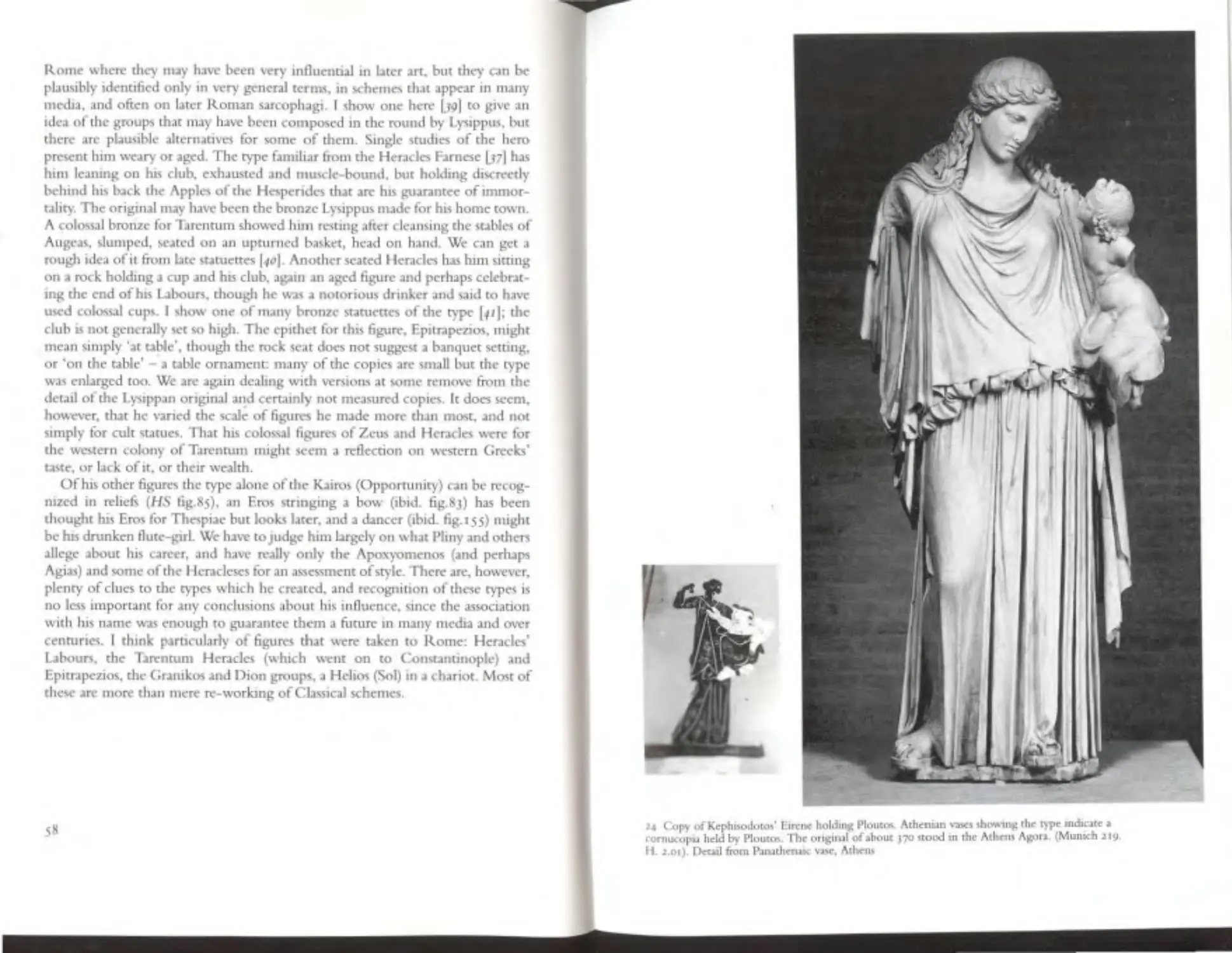

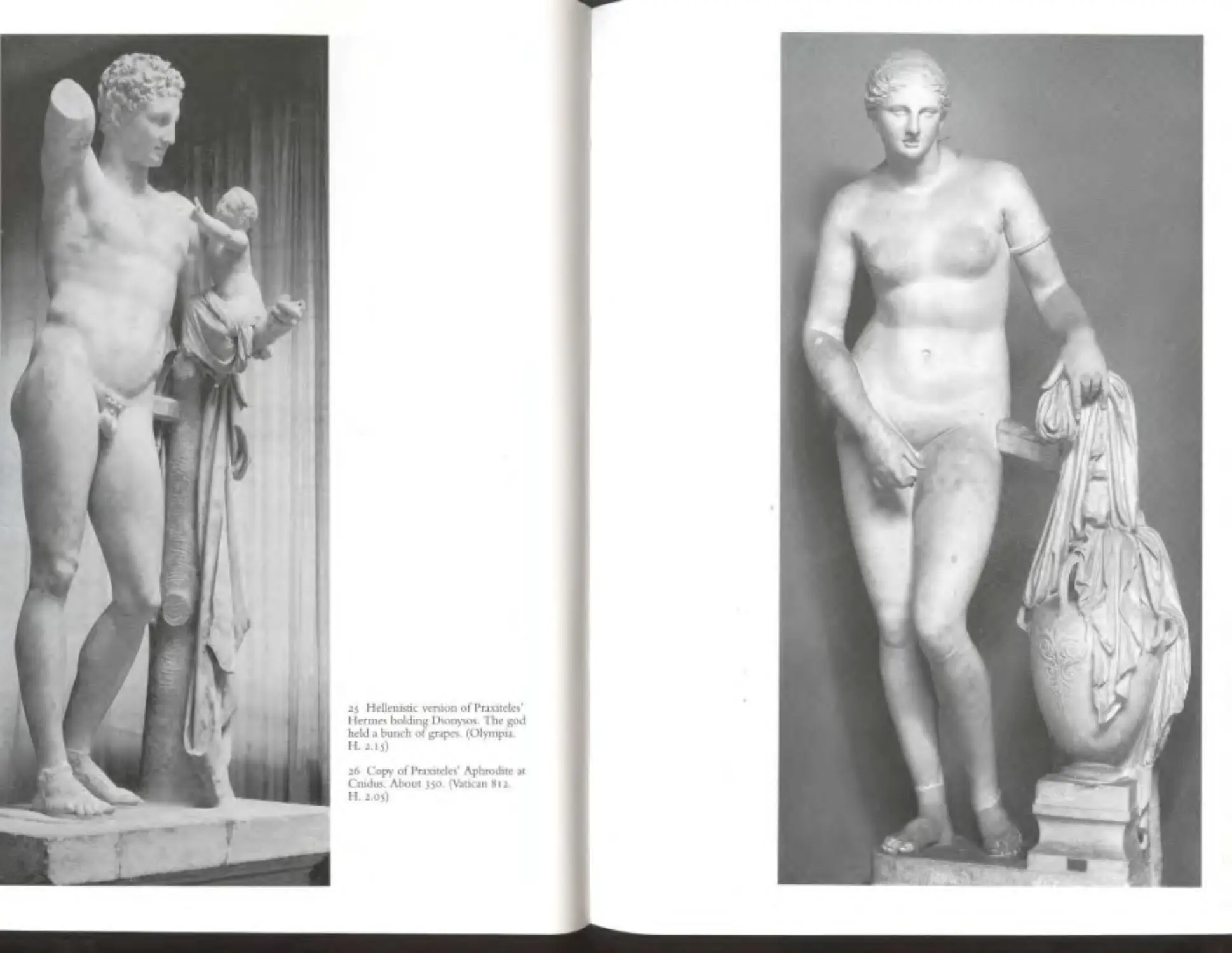

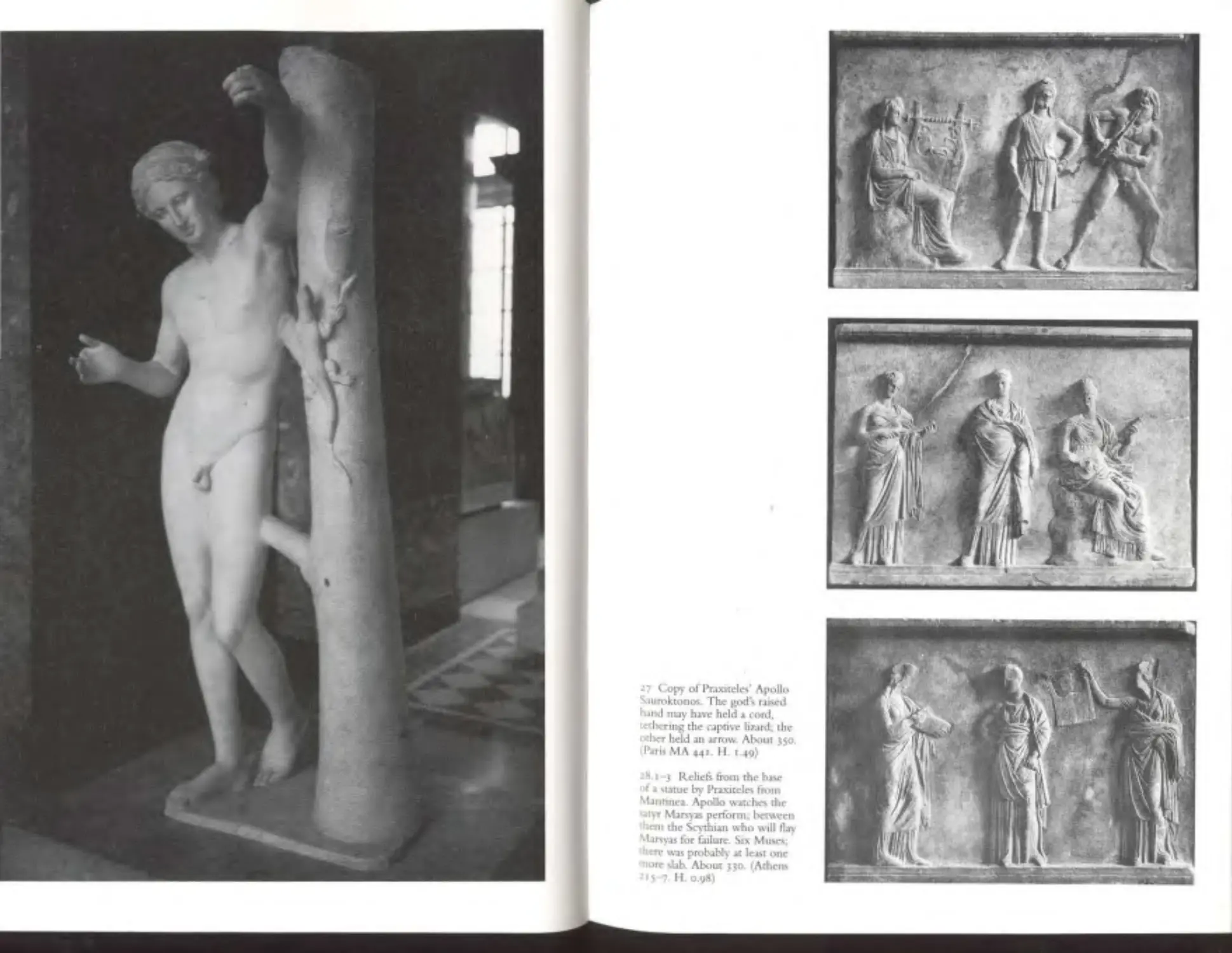

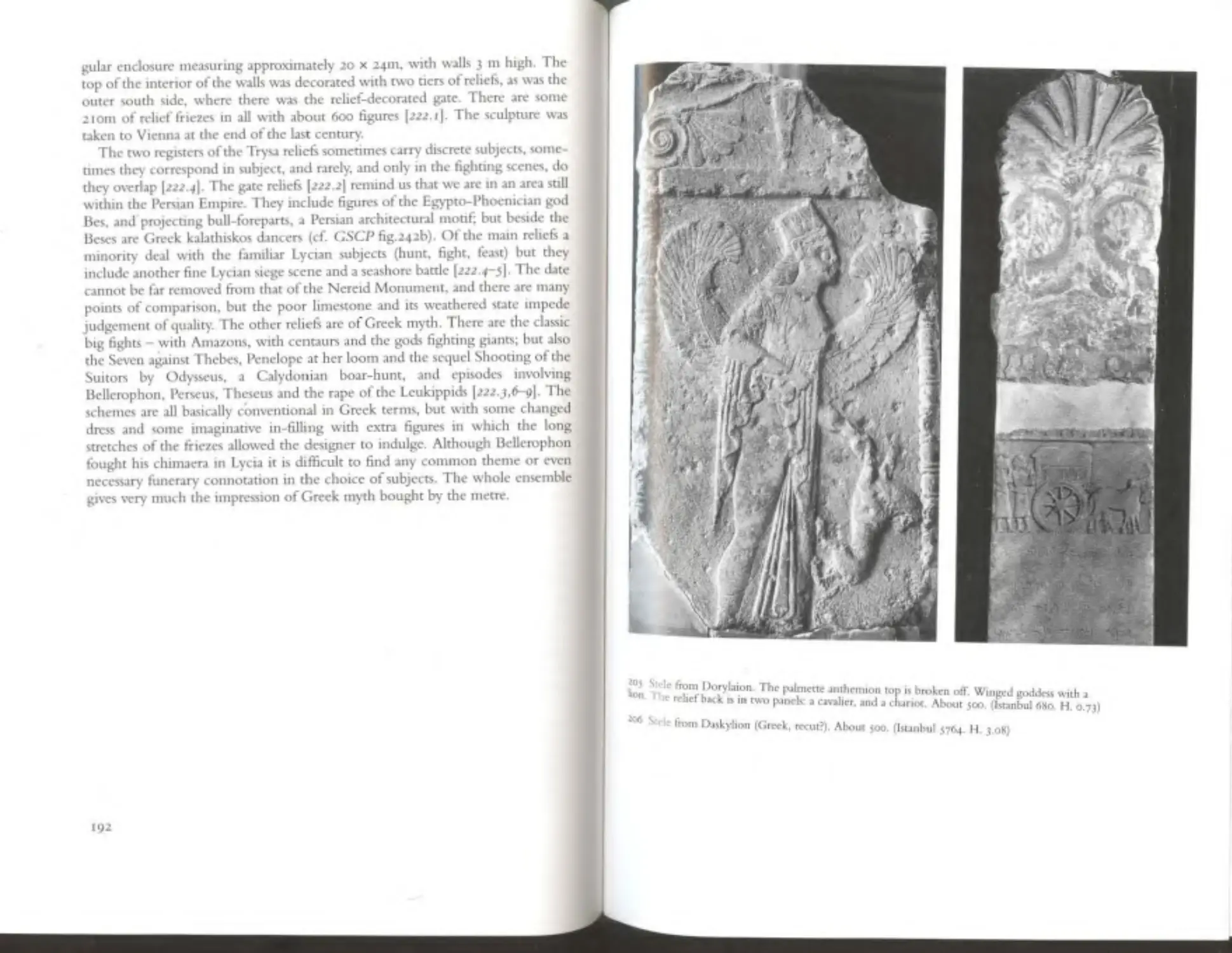

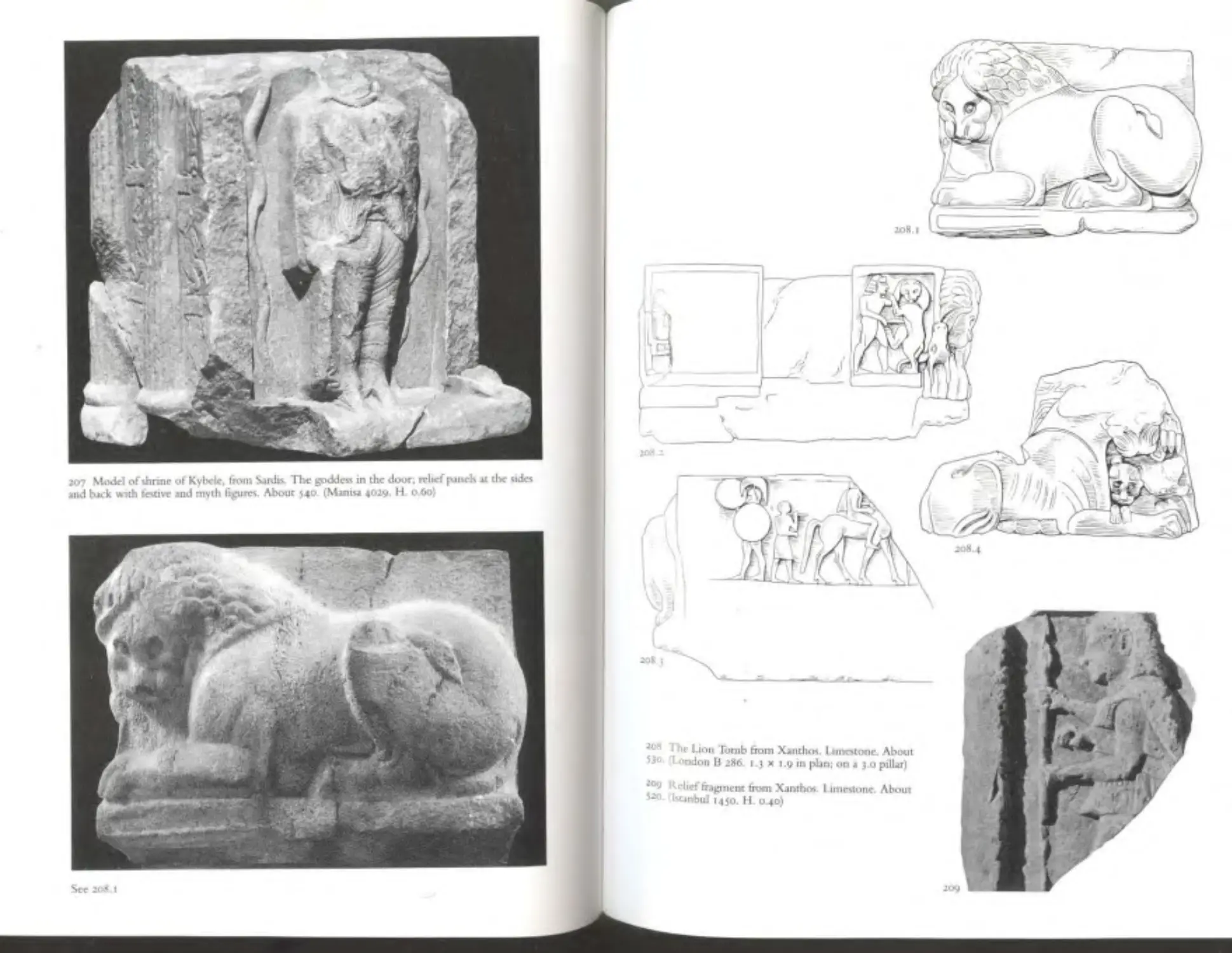

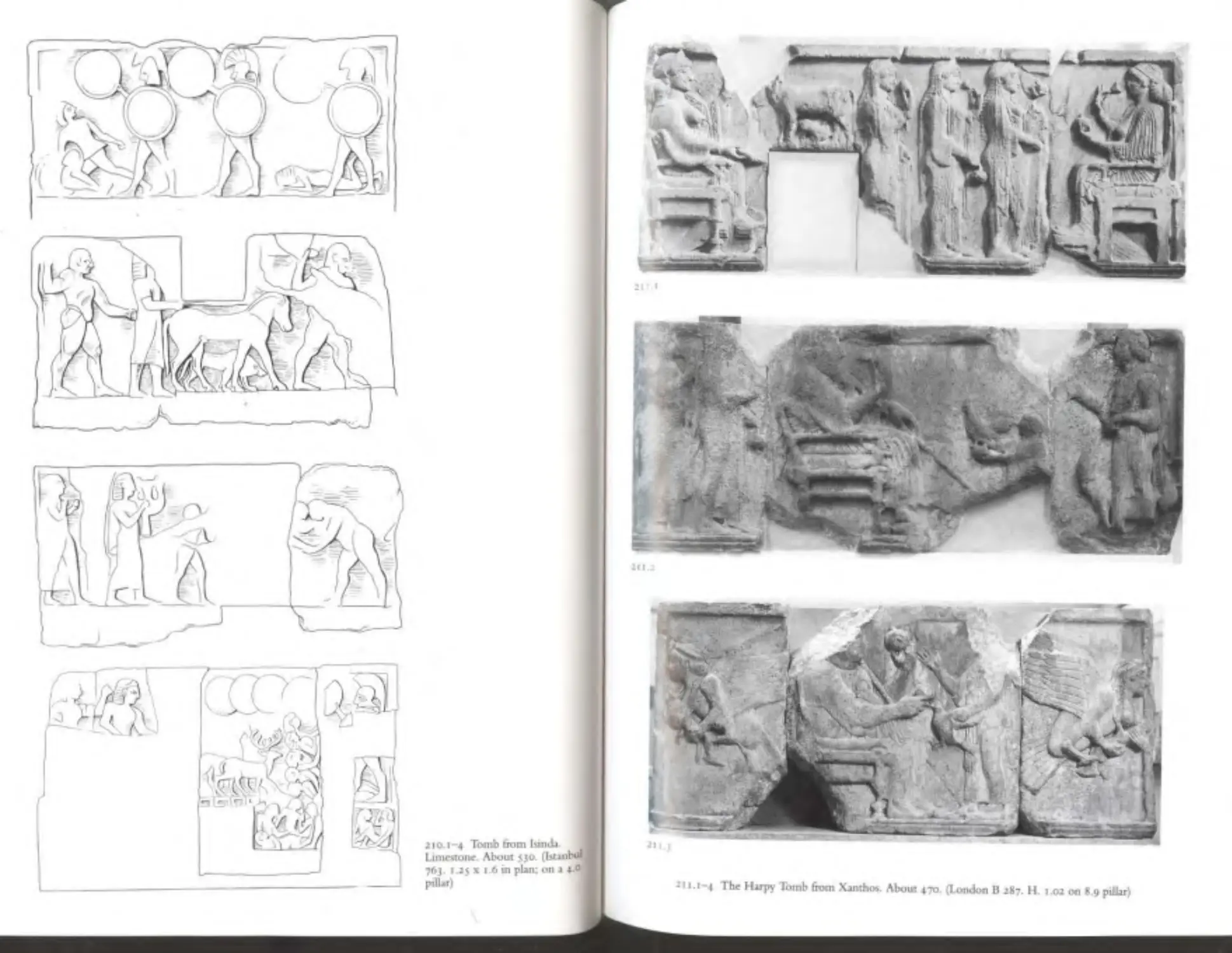

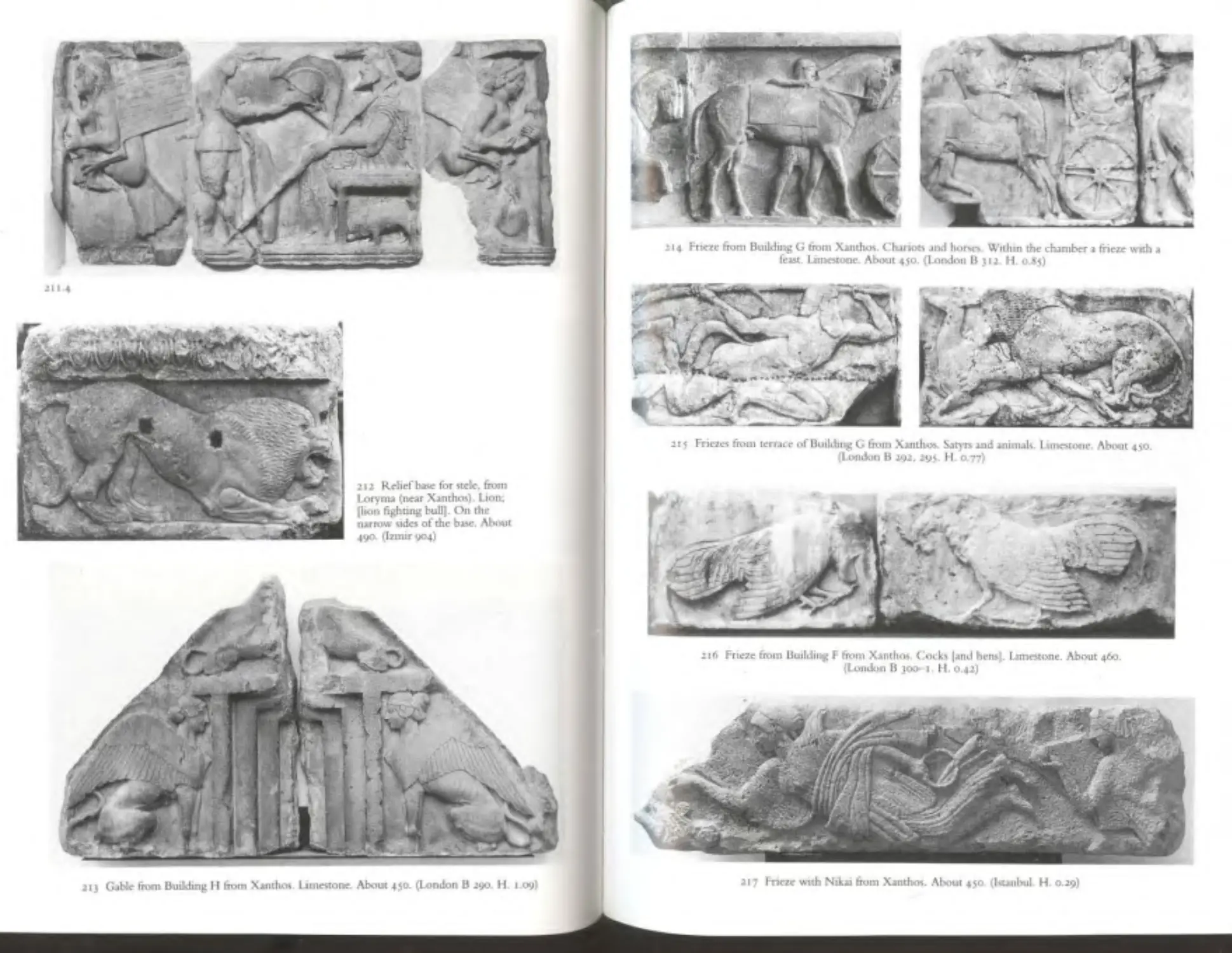

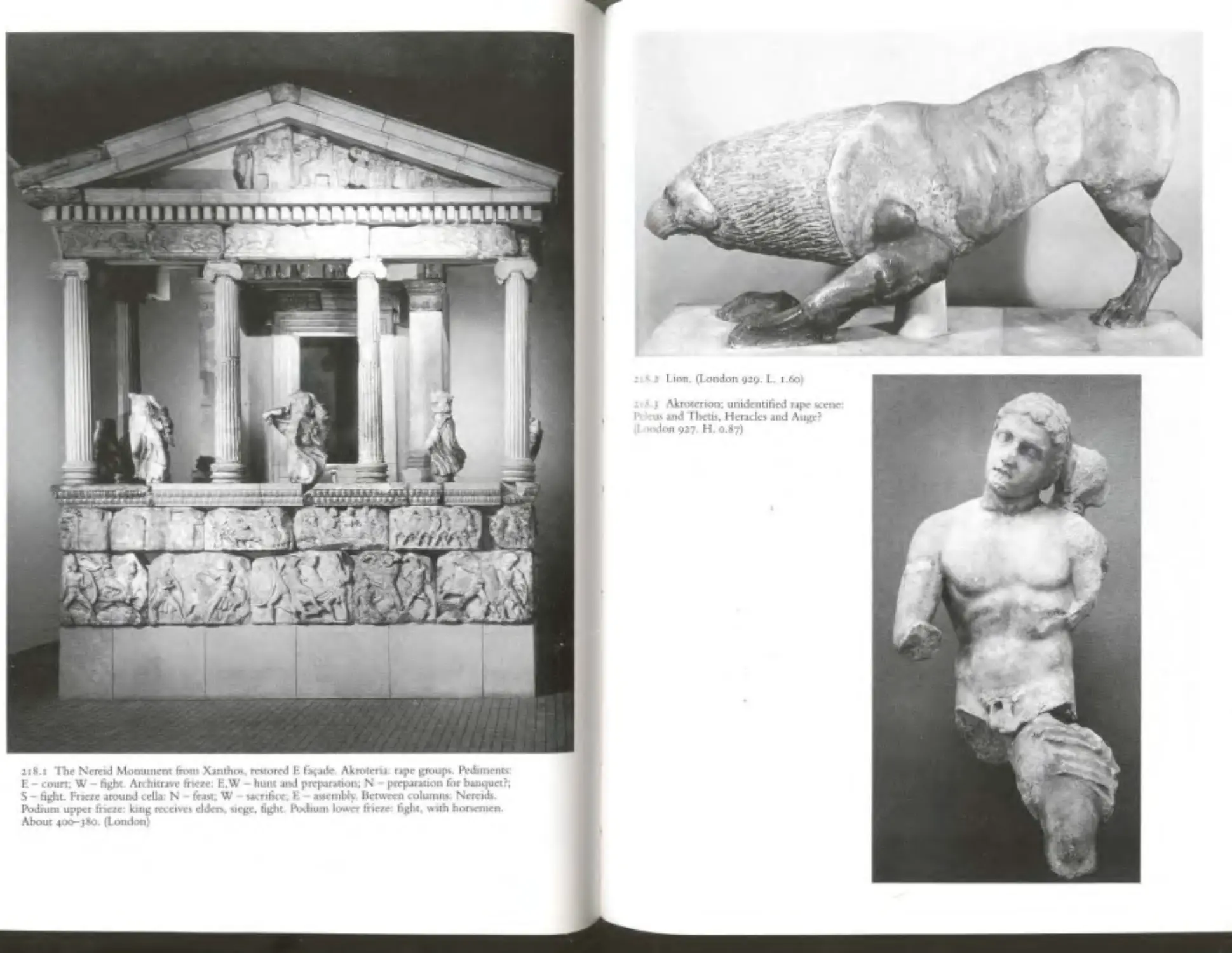

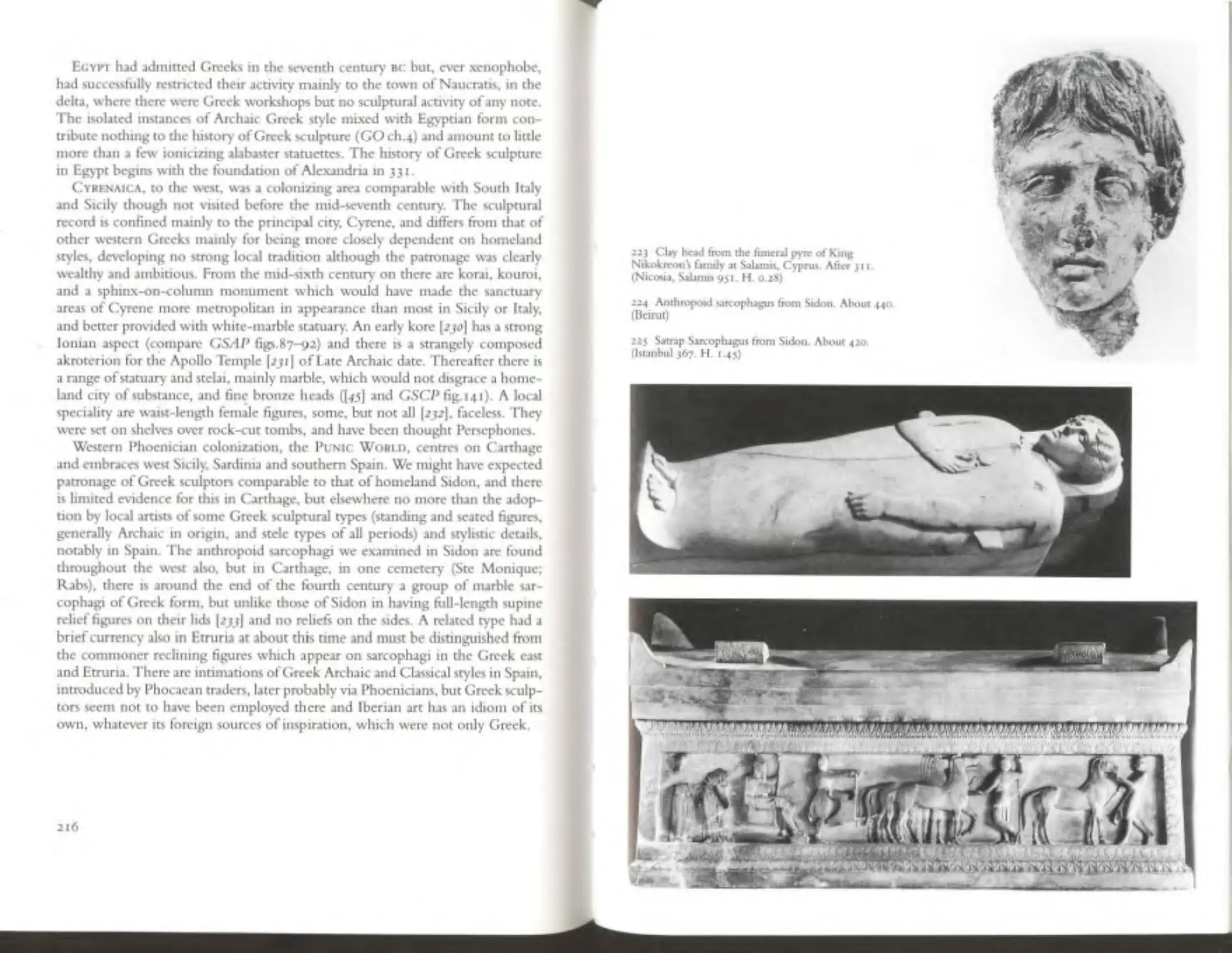

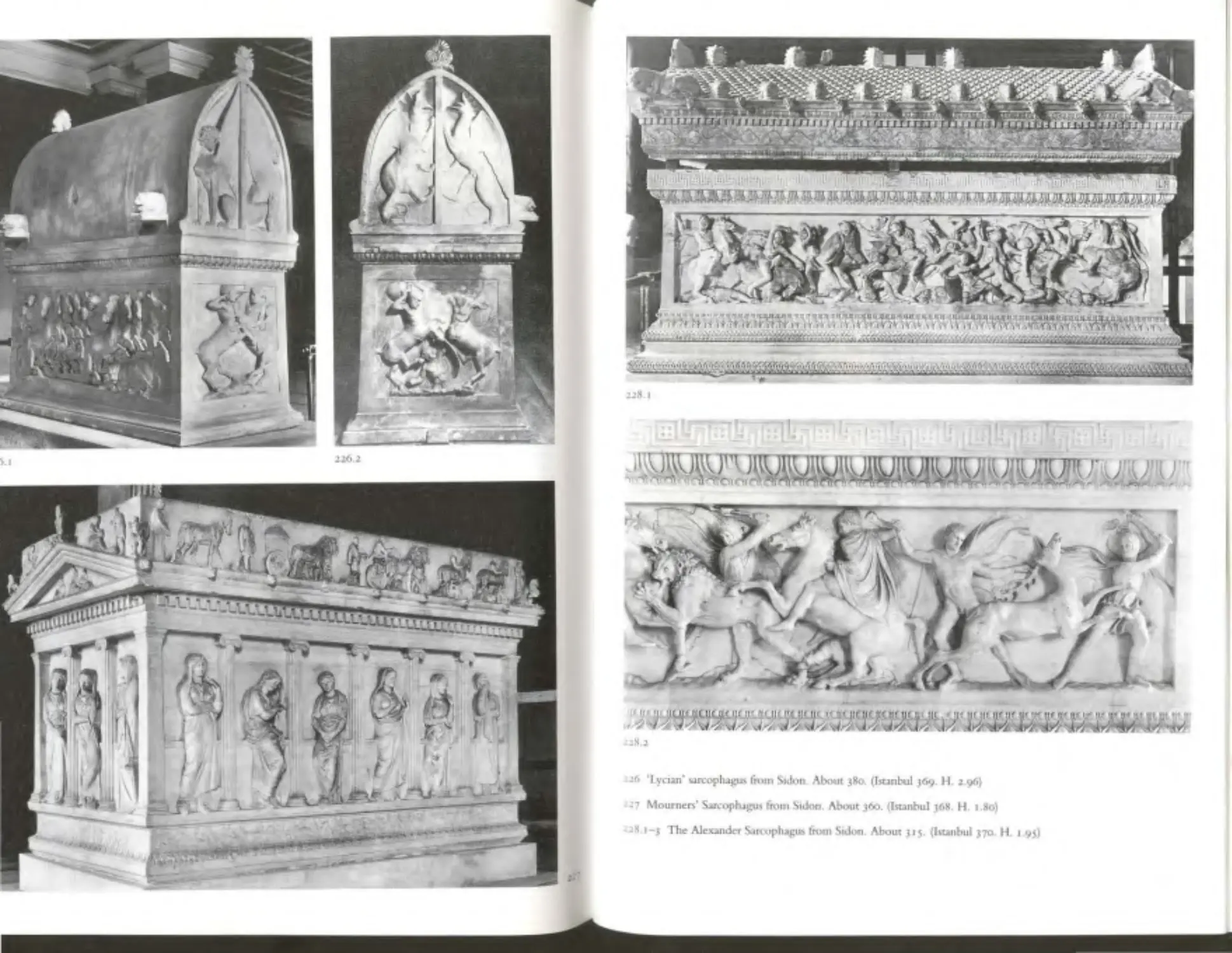

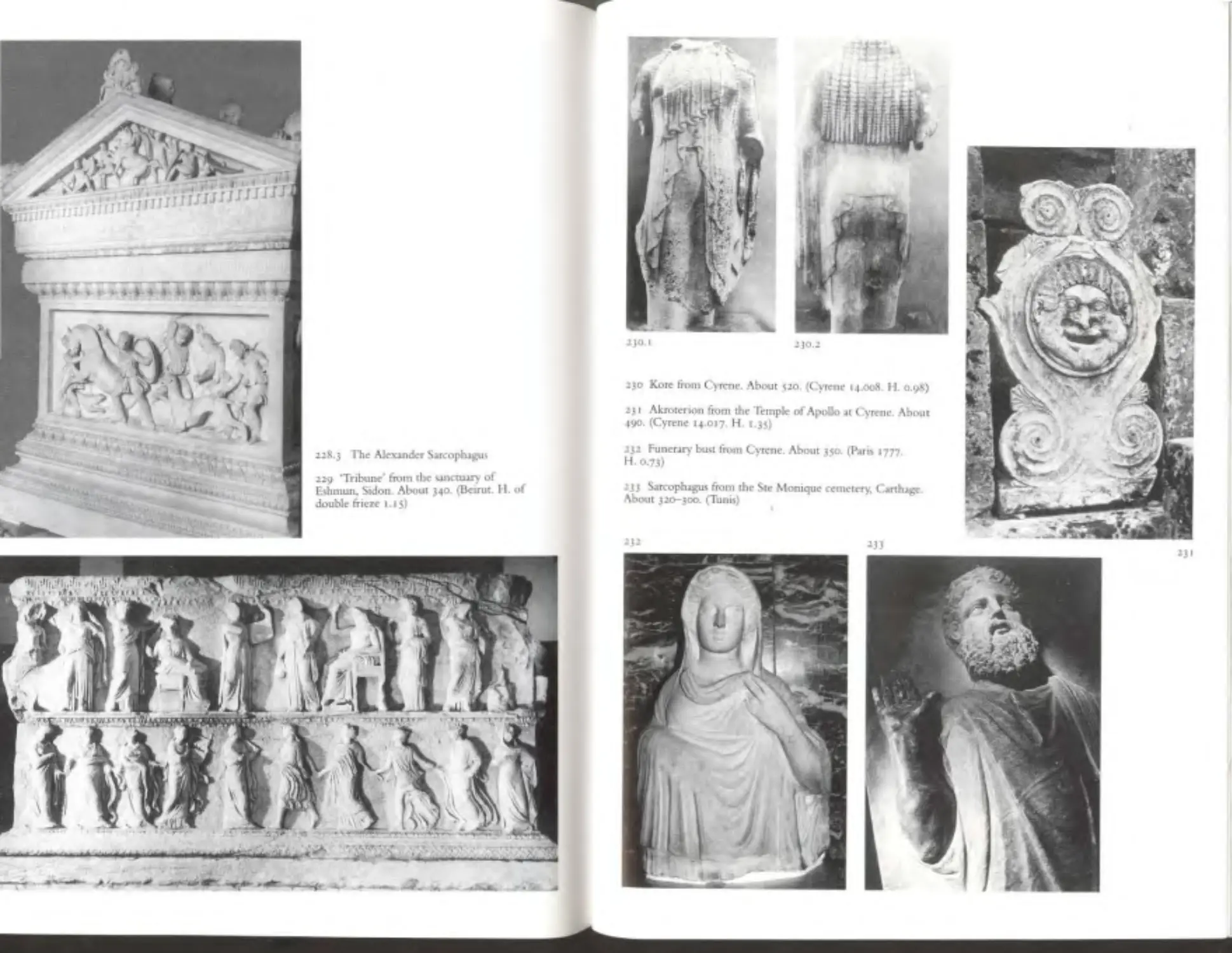

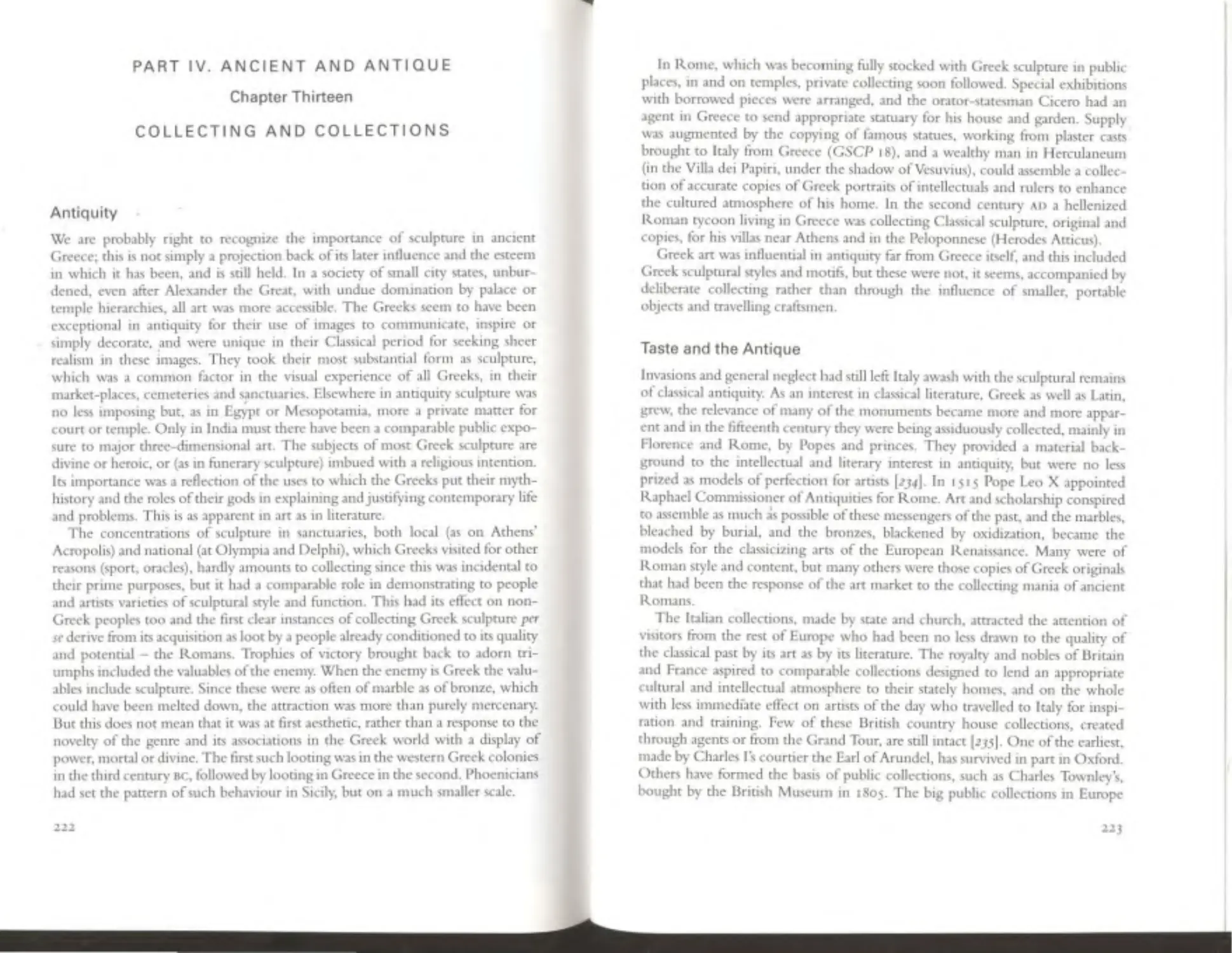

arch itectural sculpru re of Athens takes pride of place, arc mamly mtelhg•ble by