Text

SDT

|)qPN i,;f \

B

1

sSS af

IAD

SOO

re5

S

beginners

"3ah

Sa

SE

CL

LUCE

ois i

\

ee

om|

\

®~~ao|

:

>

ae“

i

d

ng me

=

==

}

>

i

a:

=

}

|

ae

|

a

tf

4f

ee

ae BS:

ye

Ly

>. [Ss

—iti -

=

Up Rees

:

%

PV

x

9

ese

Learn Old English with Leofwin

Matt Love

First Published 2013 by

Anglo-Saxon Books

Hereward, Black Bank Business Centre

Little Downham, Ely, Cambridgeshire CB6 2UA England

Printed and bound by

Lightning Source

Australia, England, USA

Revised March 2014

© Matt Love

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical

including photo-copying, recording or any information storage or

retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the

publisher, except for the quotation of brief passages in connection with

a review written for inclusion in a magazine or newspaper.

This book may not be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise disposed

of by way of trade in any form of binding or cover other than that

in which it is published, without the prior consent of the publishers.

ISBN 9781898281672

To the memory of my Mum and Dad

Thanks for everything

Unregarded, unrenowned,

men from whom my ways begin.

Here I know you by your ground,

but I know you not within —

there is silence, there survives

not a moment of your lives.

Edward Blunden, Forefathers

YA

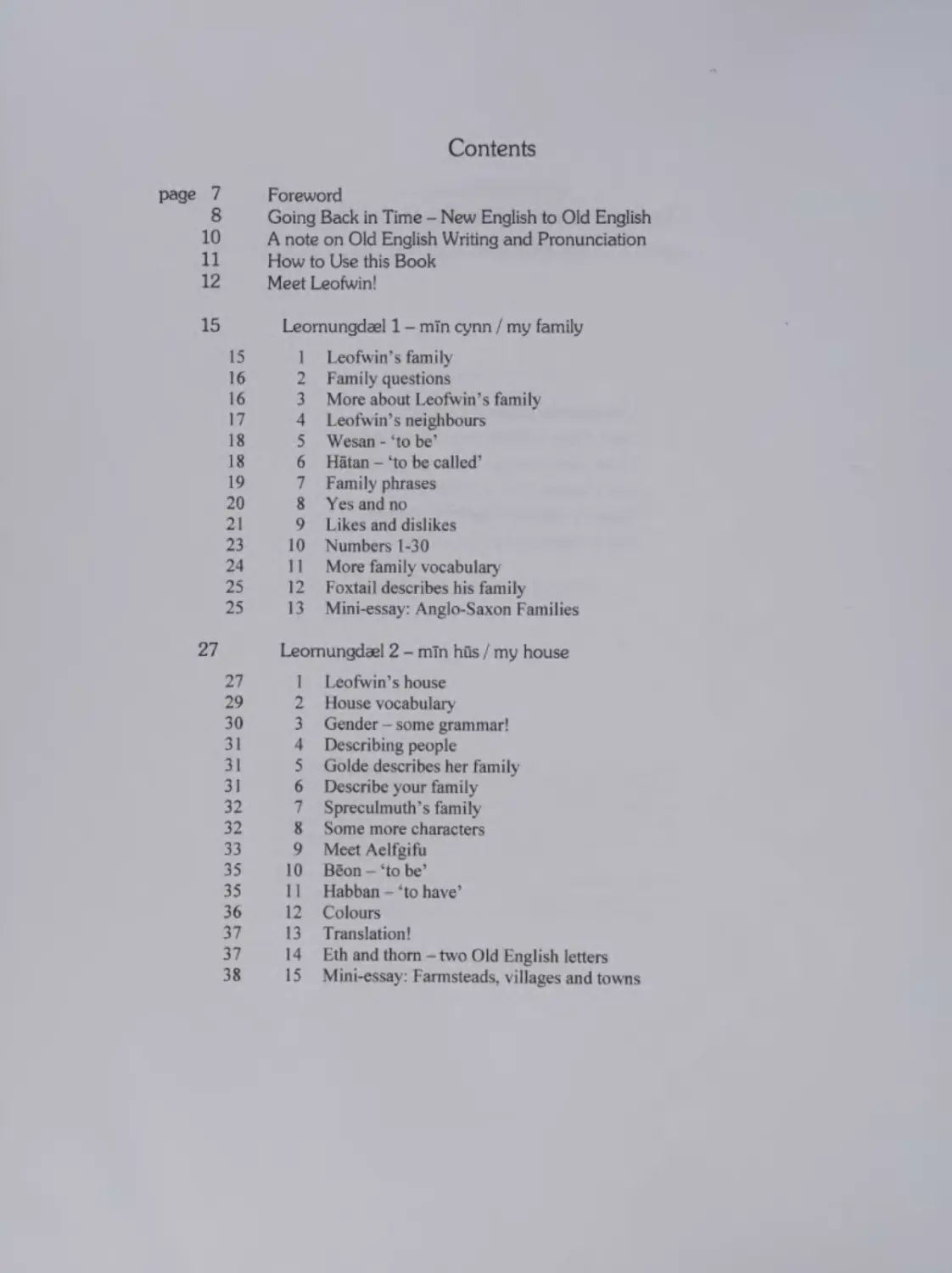

Contents

Foreword

Going Back in Time — New English to Old English

A note on Old English Writing and Pronunciation

How to Use this Book

Meet Leofwin!

Leornungdeel 1 — min cynn / my family

Leofwin’s family

Family questions

More about Leofwin’s family

Leofwin’s neighbours

Wesan - ‘to be’

Hatan — ‘to be called’

Family phrases

Yes and no

Likes and dislikes

Numbers 1-30

More family vocabulary

Foxtail describes his family

Mini-essay: Anglo-Saxon Families

Leornungdeel 2 — min his / my house

Leofwin’s house

House vocabulary

Gender — some grammar!

Describing people

Golde describes her family

Describe your family

Spreculmuth’s family

Some more characters

Meet Aelfgifu

Béon — ‘to be’

Habban — ‘to have’

Colours

Translation!

Eth and thorn — two Old English letters

Mini-essay: Farmsteads, villages and towns

page 39

Leornungdeel 3 — iite / outside

39

1 Where Leofwin lives

40

2 ‘oneardian’ - to inhabit

40

3. Plurals - examples so far

42

4 Plurals — strong and weak nouns

43

5 Strong and weak nouns - test

44

6 Leofwin describes his village

46

7 Some verb patterns

47

8 Animals

48

9 Consolidating plurals - strong and weak nouns

48 10 Subjects and objects — more grammar!

49 11 Weak nouns

51 12. Word order

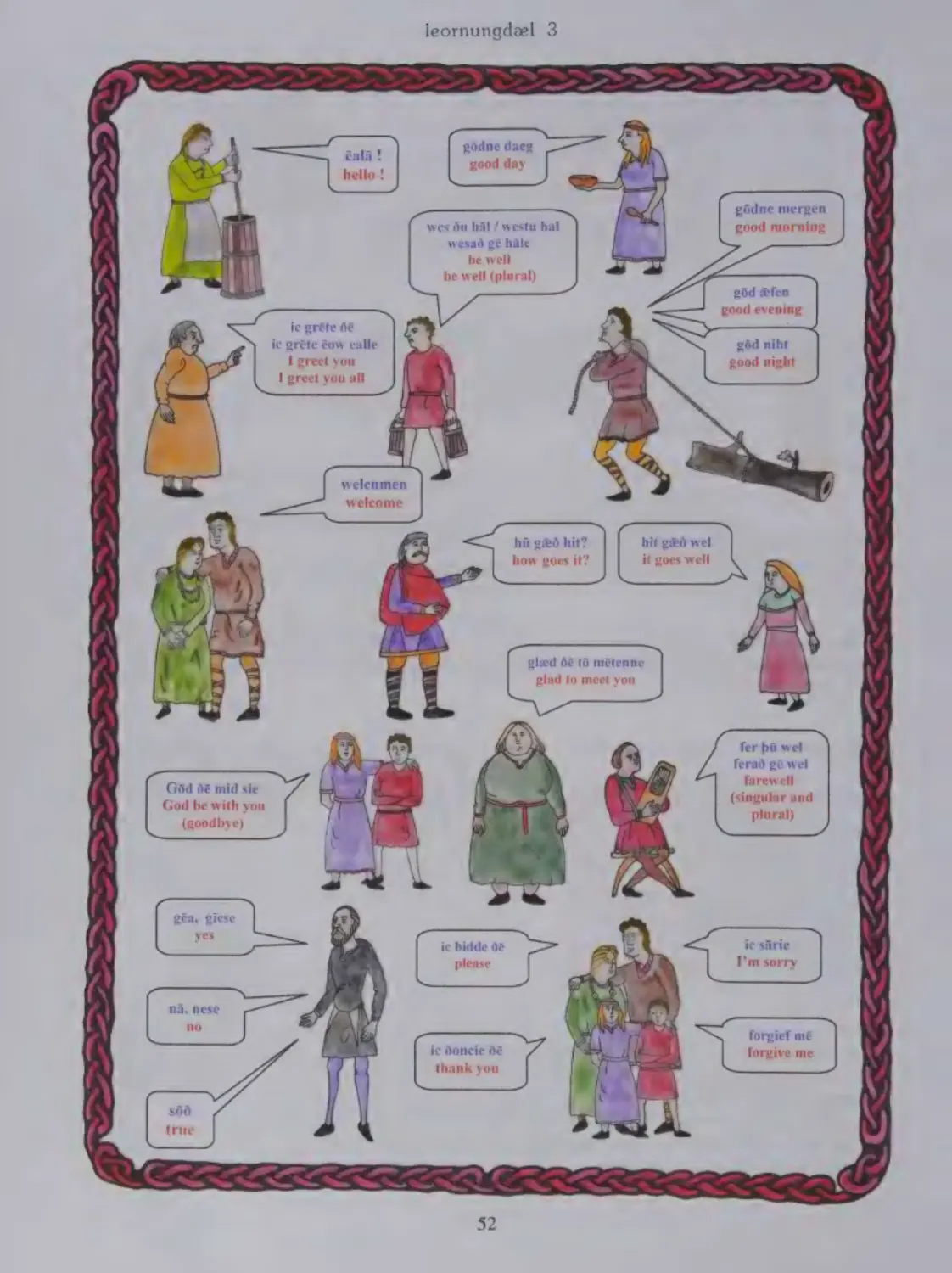

51 13 (aand b) Basic survival guide — some essential phrases

54 14. Mini-essay: Prittlewell in Anglo-Saxon times

55

Leornungdeel 4 — timan, weder / seasons, weather

55

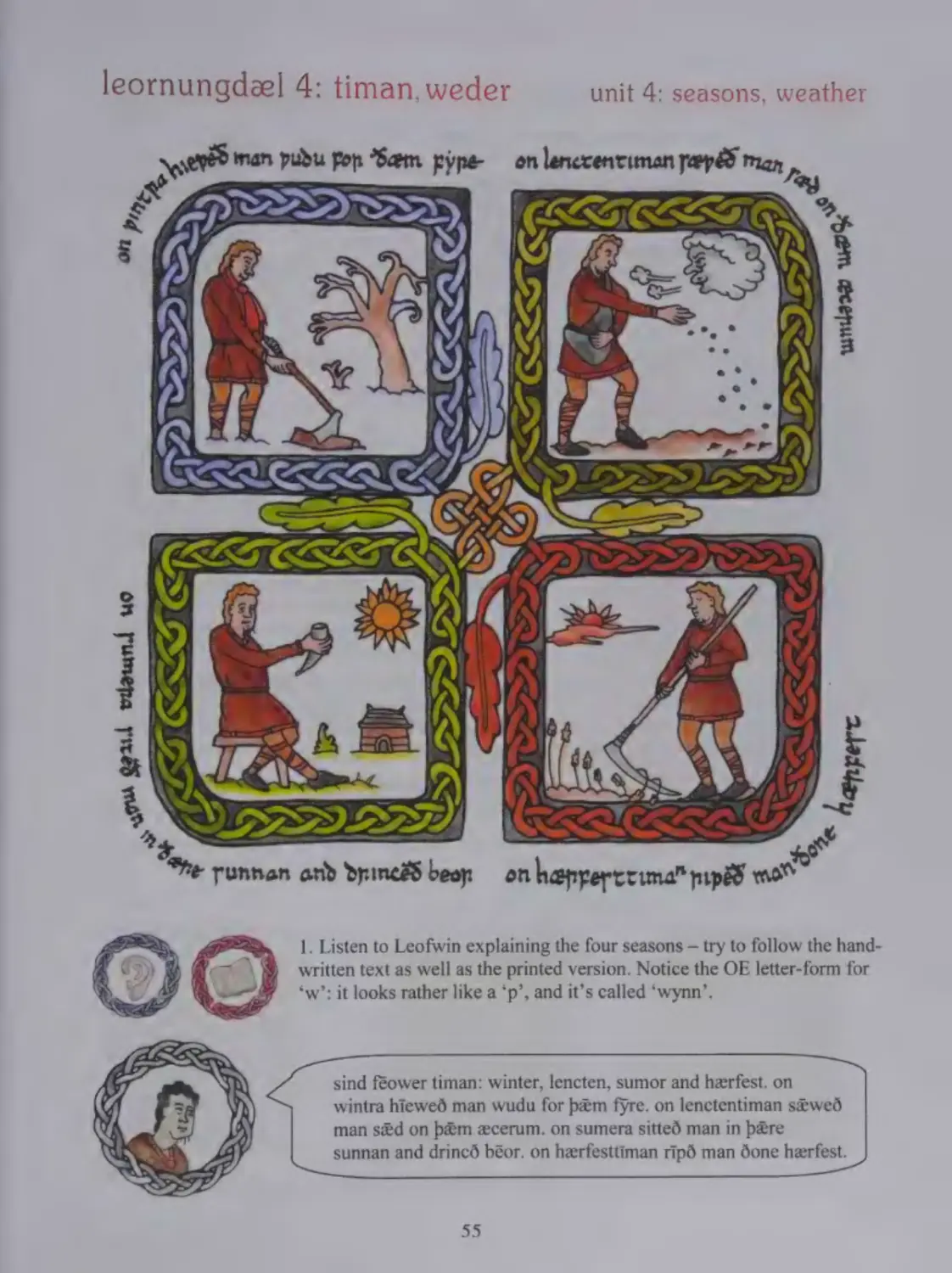

1 The four seasons

56

2 Reading task (easy!), and discussion on verbs

oy| 3. Fairly easy translation task

58

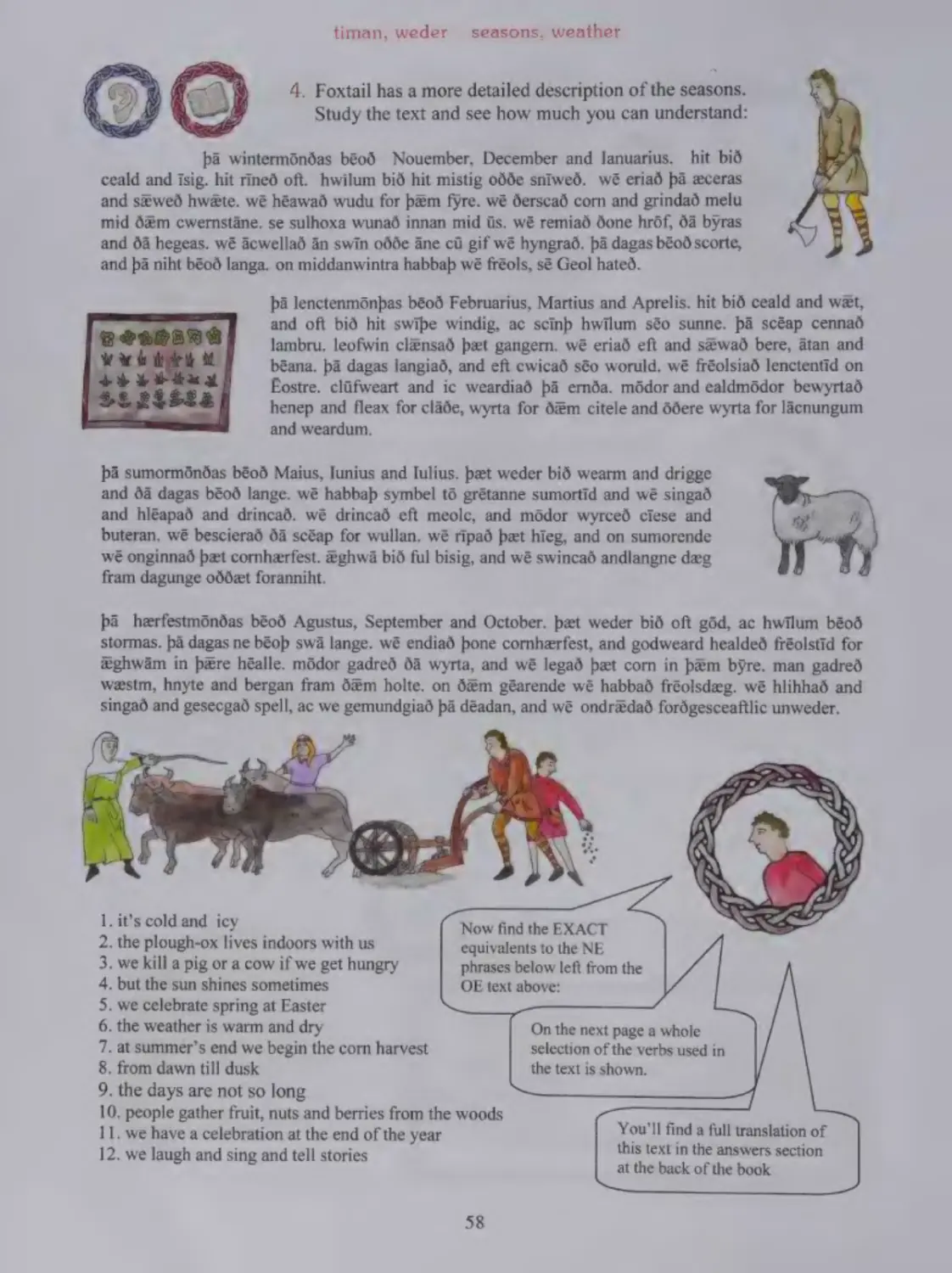

4 Foxtail describes the seasons — and offers a feast of verbs

60

5 Grammar task on verbs

61

6 Months of the year (harder than you’d think)

63

7 Birthdays

64

8 Numbers 31 — 100

65

9 Weather

66

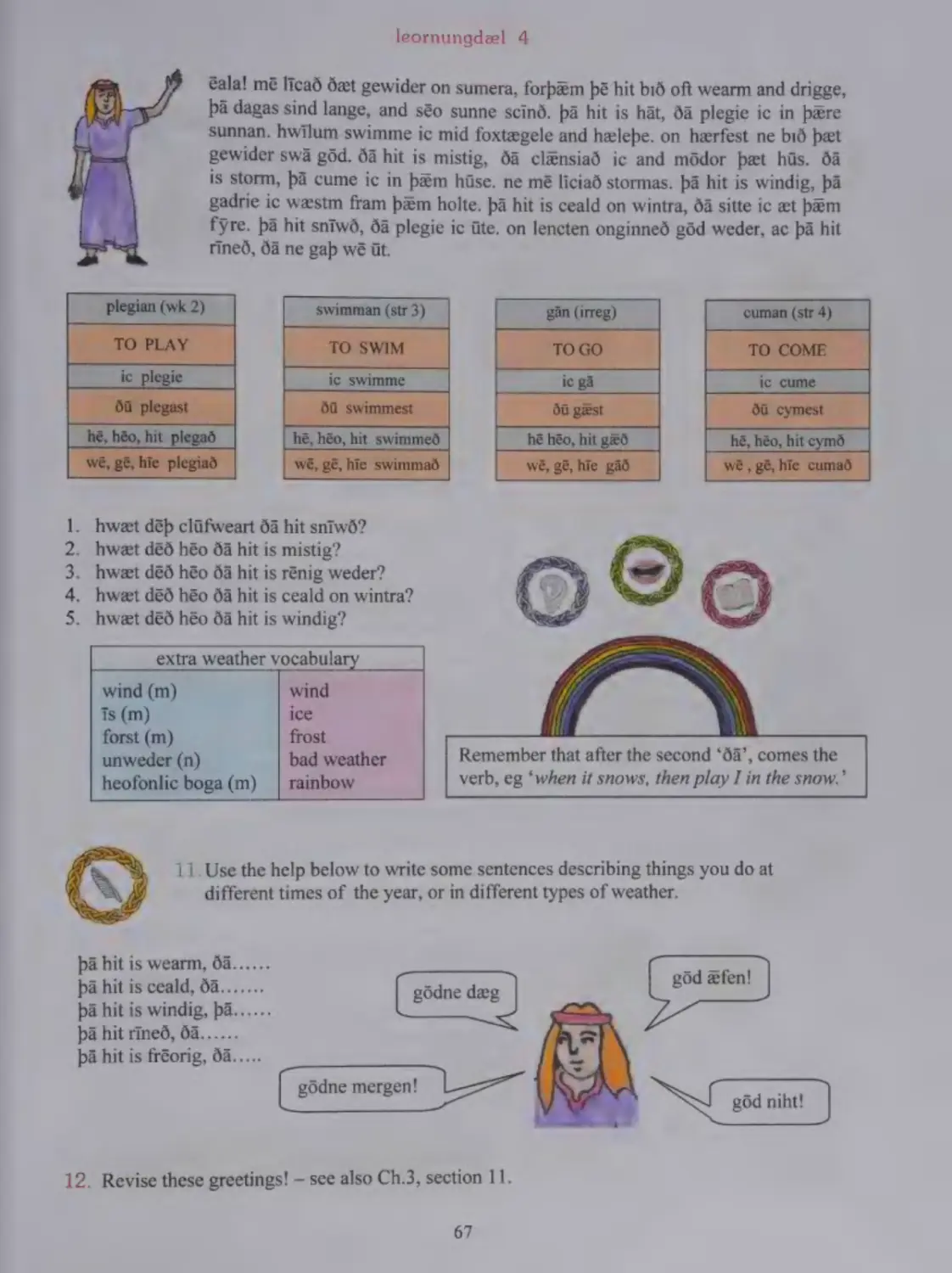

10 Clufweart talks about the weather

67 11 Writing about the weather yourself

67 12 Revision of greetings

68 13. Days of the week

69

14. (a) Times of the day

(b) Hours of the day

70 15 Mini-essay: dividing the year

7

Leomungdeel 5 - gesceaftlice woruld, gedaeghwamnlic lif/natural world, daily life

a

1 Leofwin’s world

a

2 Wordsnake

13

3 More on Leofwin’s world

74

4 ‘this’ — some grammar, and a test!

ie) 5 Leofwin’s daily routine

7

6 Tasks on daily routine

78

7 More on daily routine

80

8 Consolidation of verb patterns

83

9 Mini-essay: the Round of the Year

page 87

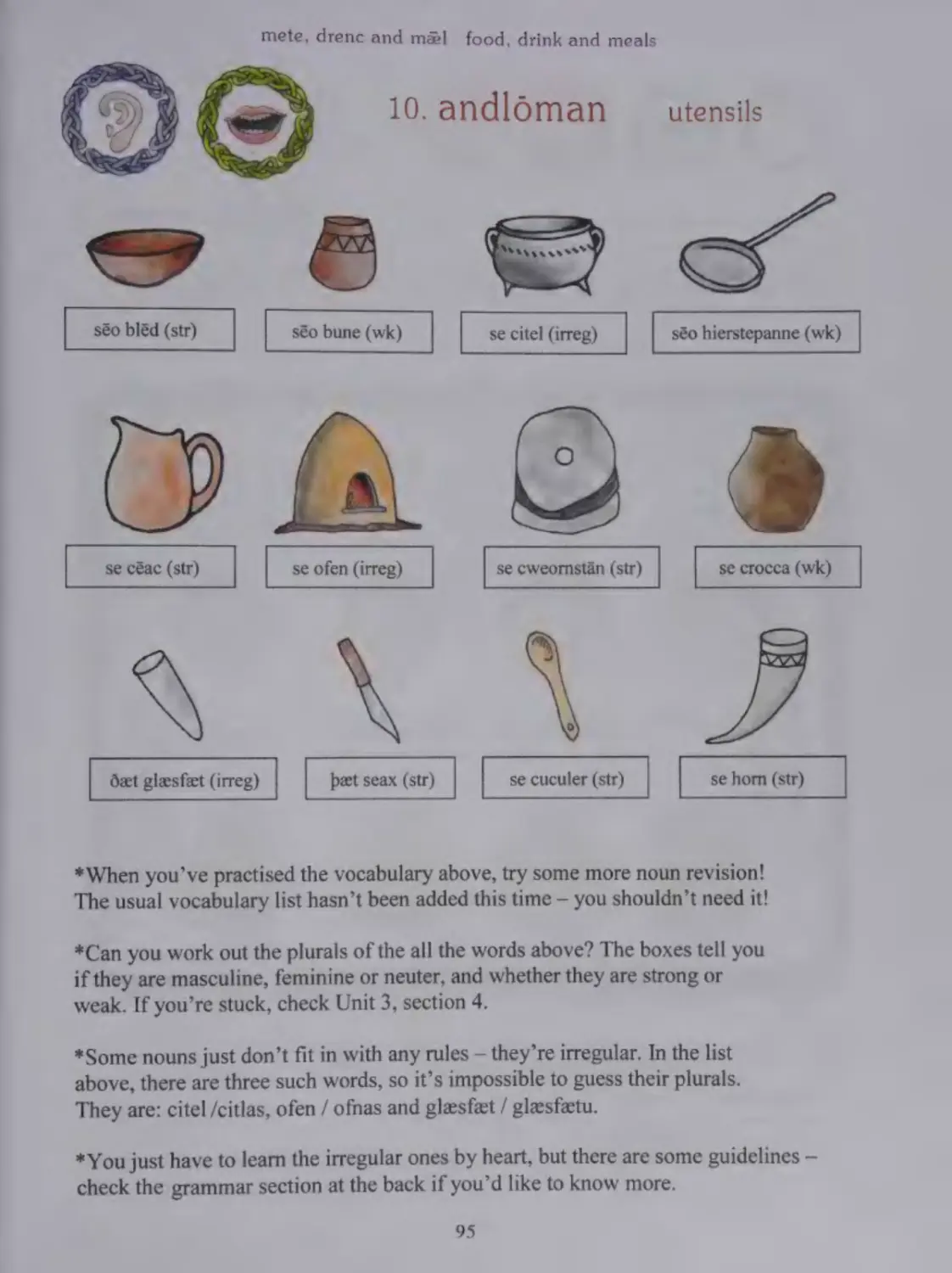

Leornungdeel 6 - mete, drenc and mé!l / food, drink and meals

1 Clufweart milks the cow

2 Food and drink vocabulary

3. Revision of plurals and checking of new vocabulary

4 (a) Foxtail talks about mealtimes

(b) Mealtimes — true, false or unknown

5 ‘drincan’, to drink and ‘etan’, to eat

6 More on mealtimes

7 Leofwin asks you about your mealtimes

8 Talking animals: translation

9 ‘niman’ to take, and ‘giefan’ to give

10 More food and drink vocabulary

11 Revise likes and dislikes

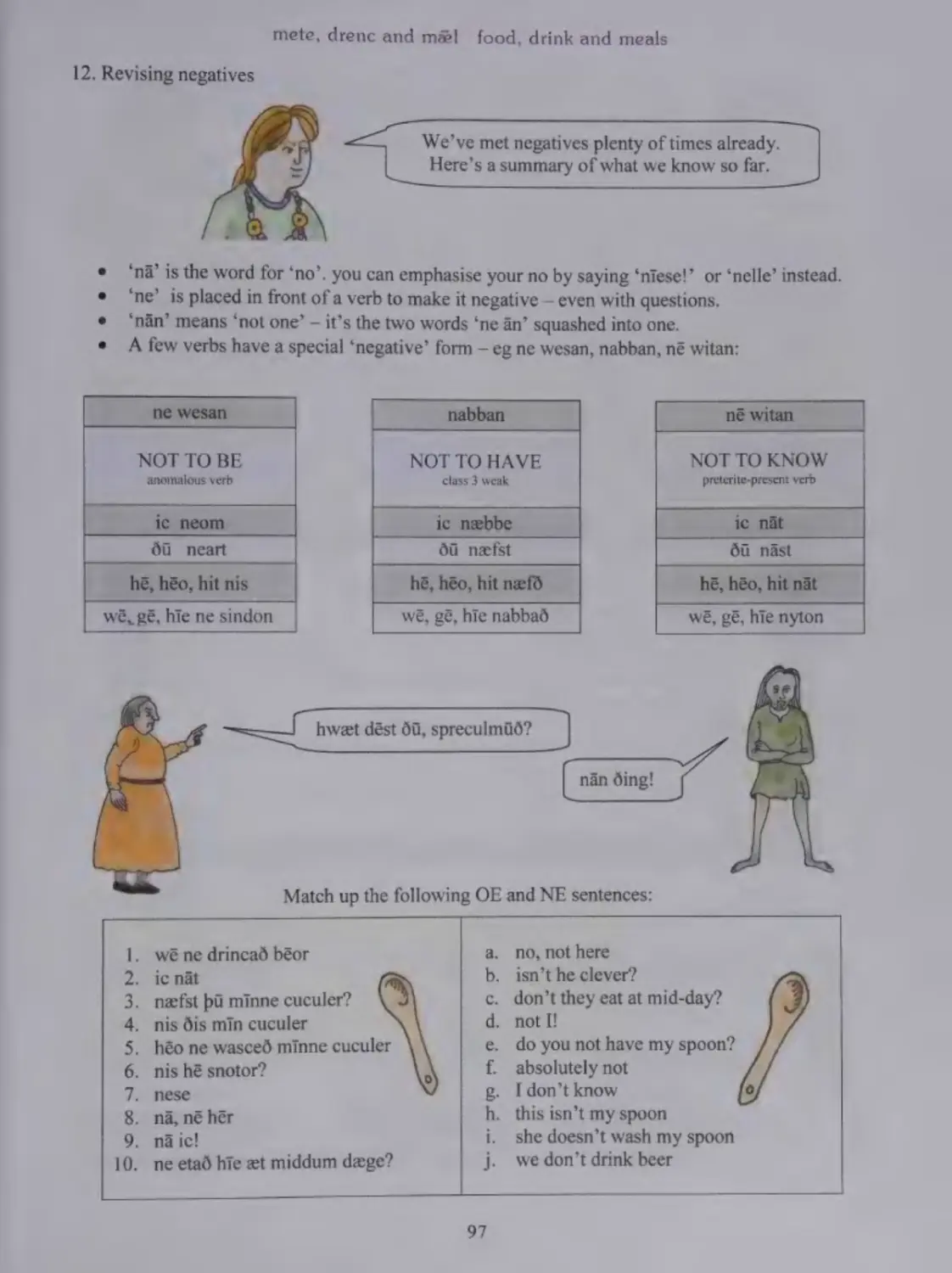

12 Revision of negatives

13. Leofwin describes Easter

14. Three new verbs — cooking, catching, answering

15 Belonging — possessive adjectives

16 Ealhstan’s Easter Sermon

17 Mini-essay — food and drink / cooking and eating

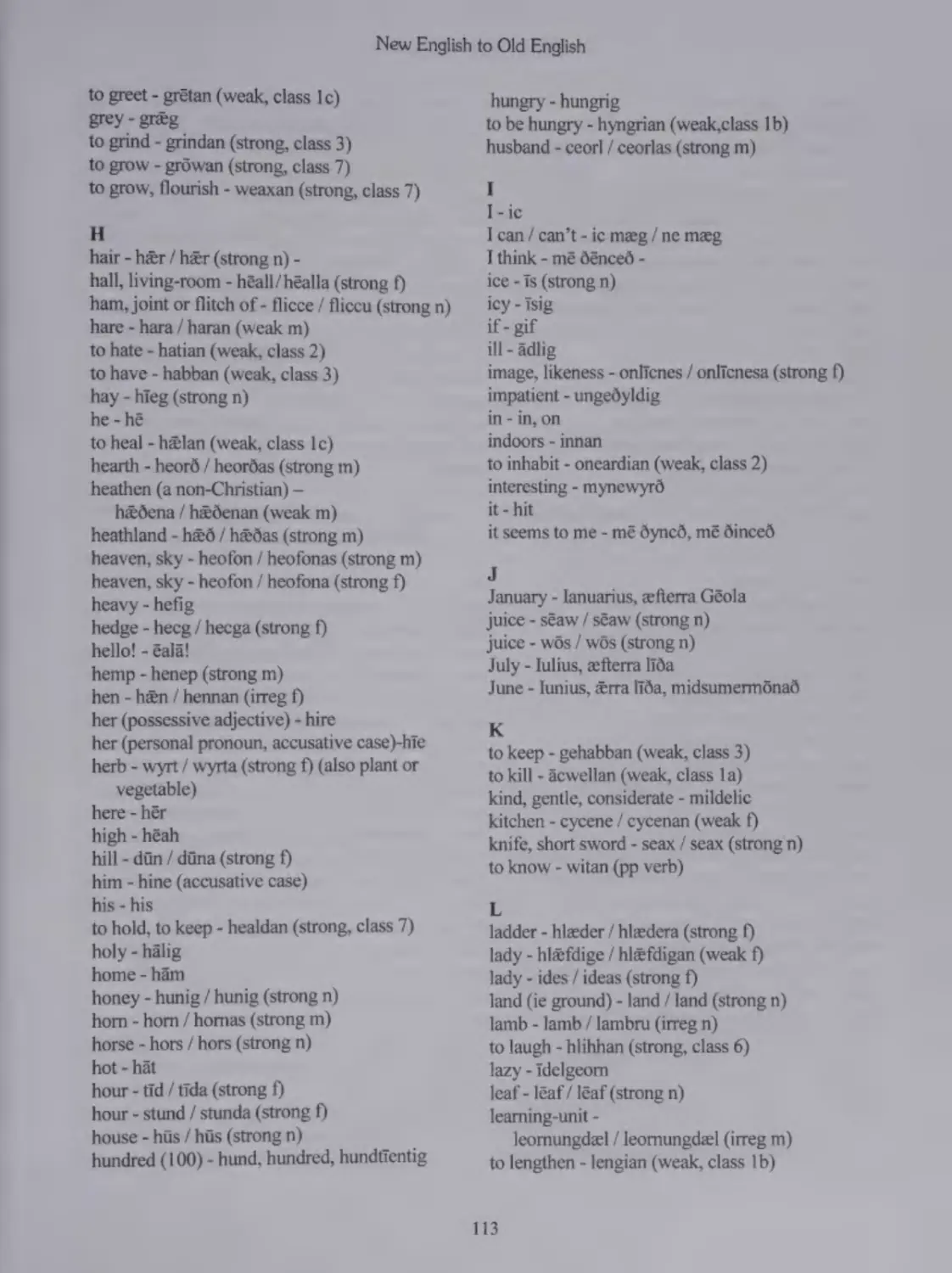

Vocabulary: New English (NE) to Old English(OE)

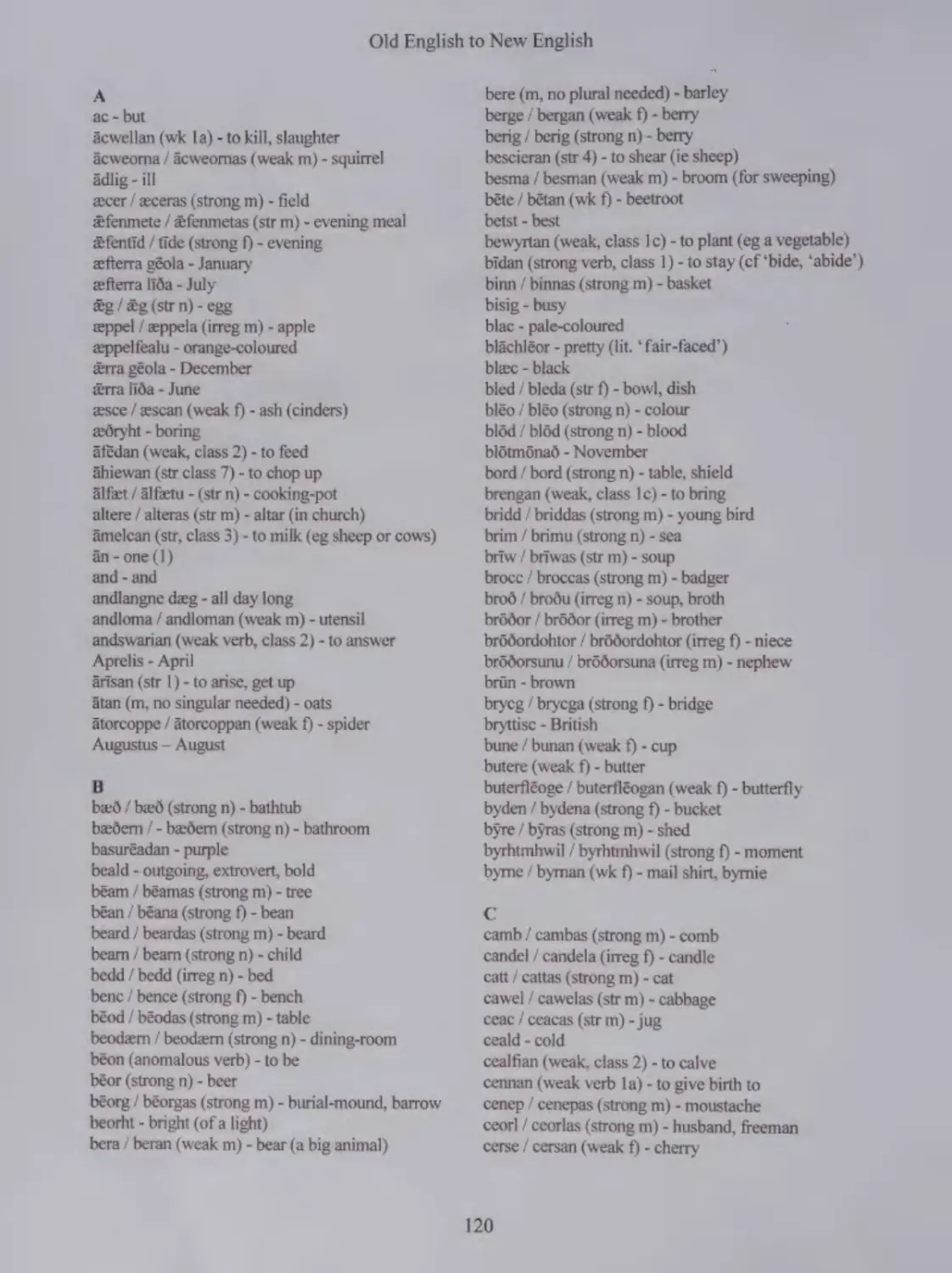

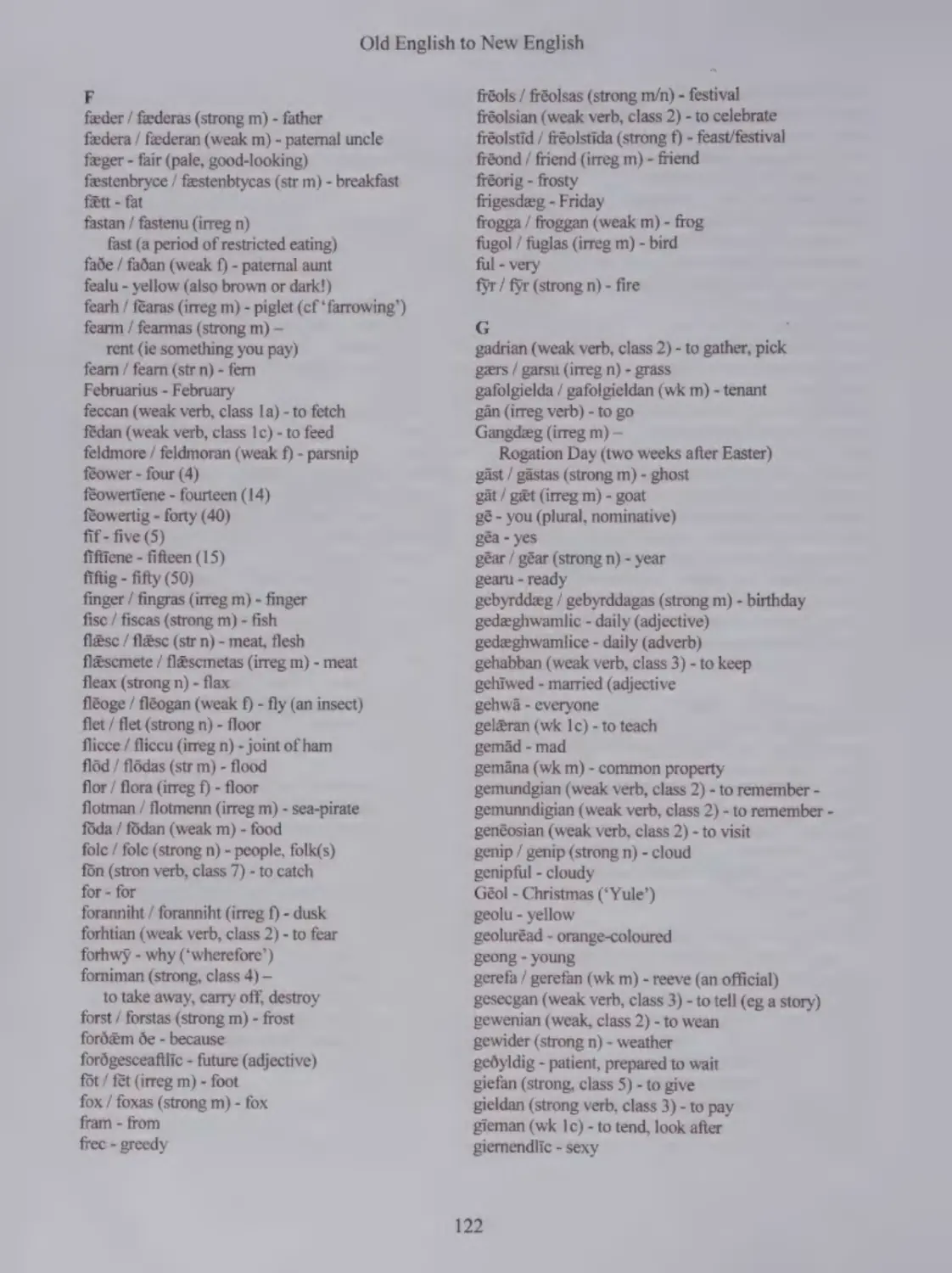

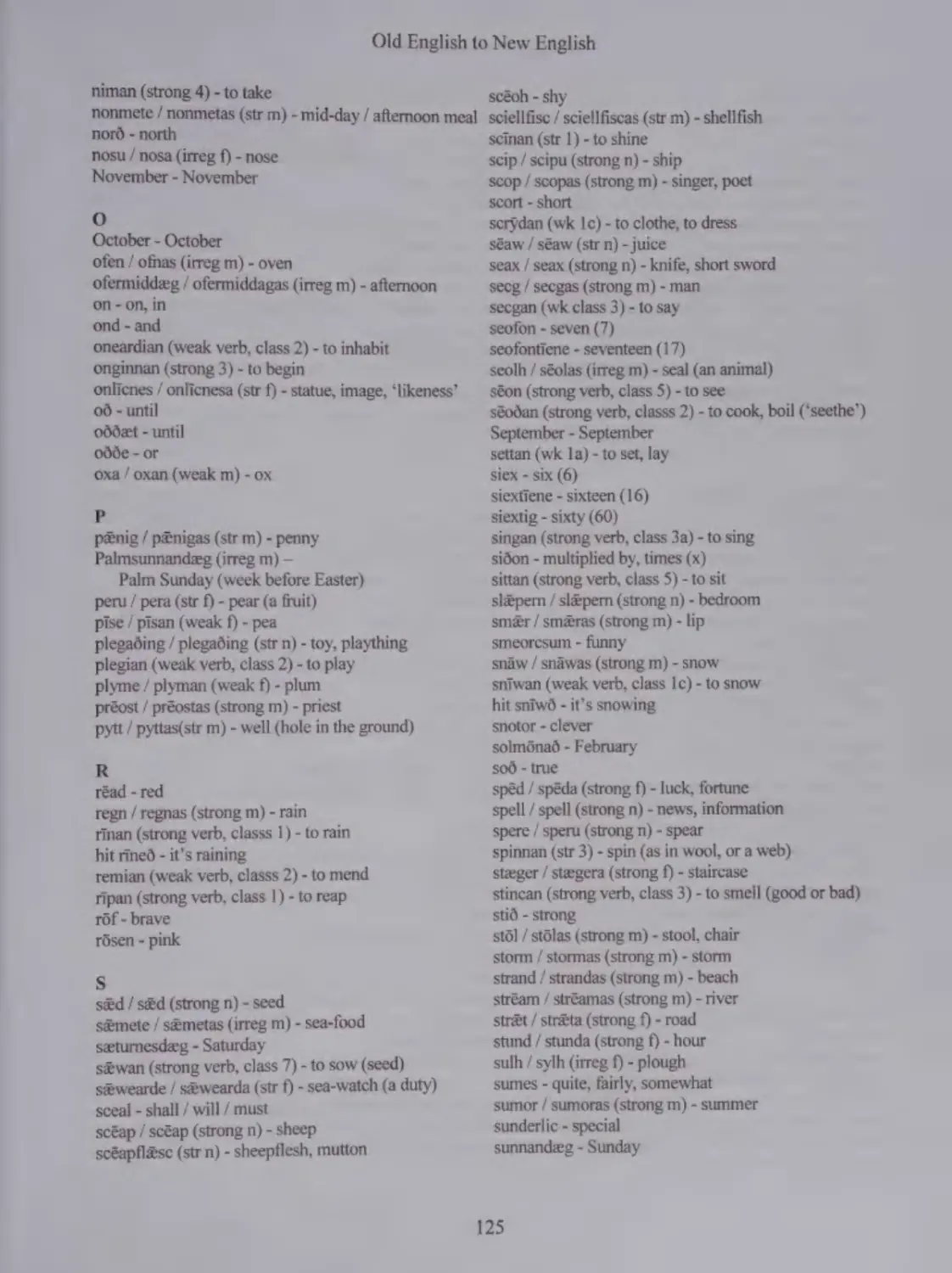

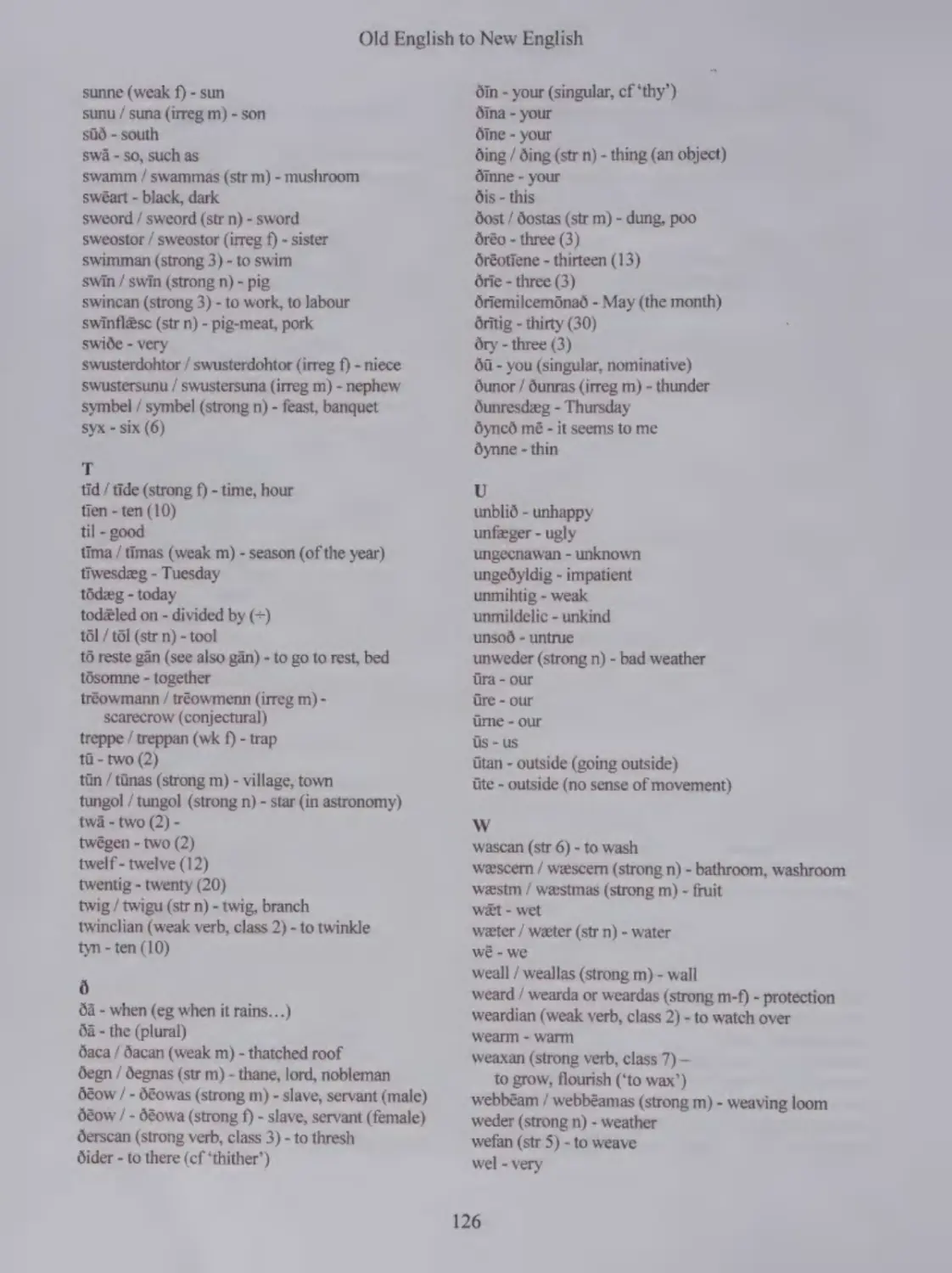

Vocabulary: Old English (OE) to New English (NE)

Transcripts and Answers

Grammar Summary

Foreword

Nearly ten per cent of the people on our planet speak English either as their mother tongue,

or as a first foreign language of choice. It’s a global language. But where did it come from?

How long has it been around? How much has it changed over time?

This book aims to give the reader who is not a language specialist a glimpse of the English

language as it was spoken over a thousand years ago by a couple of million people on a

green and pleasant island off the coast of mainland Europe.

Old English, as it is called, or Anglo-Saxon, survives in a fairly substantial number of

manuscripts, which include laws, charters, wills, histories, religious works, poetry,

medical and scientific treatises and other material. If everything were collected together,

it would take up the equivalent space of about forty or so medium-sized books. The

material dates from the 8" to the 11" century, during which time the language was

evolving constantly; it continues to do so today.

There are, of course, gaps, regional variations, and since what survives is necessarily rather

‘bookish’, there are some aspects of the everyday language which can only be inferred.

Nevertheless, it is this everyday language of Anglo-Saxon England that I’ve tried to present

in this book. Old English tends rather to be the playground of paleo-linguists and

philologists, who are interested primarily in how language changes over time and in the

relationship of languages to each other. Although there’s a fairly wide range of books on

Old English, many can appear rather intimidating and inaccessible to anyone who’s not

already heavily involved in this kind of study.

‘Leofwin’ presents Old English, as far as possible, as if it were a living language, and I

hope it will fill the need for a lively, entertaining and attractive introduction for anyone

interested in the roots of our quirky and marvellous tongue.

My thanks are due to David Cowley, who checked the draft text, and to Steve Pollington,

who put me up to the whole project. Also to Linden Currie, and my other friends in ‘The

English Companions’, who’ve given me every encouragement. To Maria Legg, who

provided all the female voices in the audio passages, and to the wonderful people of

‘Centingas’, who share my passion for Anglo-Saxon Living History. To my son Thomas,

for all his help with computer issues, and finally to Tony Linsell of Anglo-Saxon books,

for whose patience, support, guidance and gentle criticism I’m very grateful. Whatever

errors still lurk within these pages are, of course, my own responsibility.

MWL, Leigh-on-Sea, September 2012

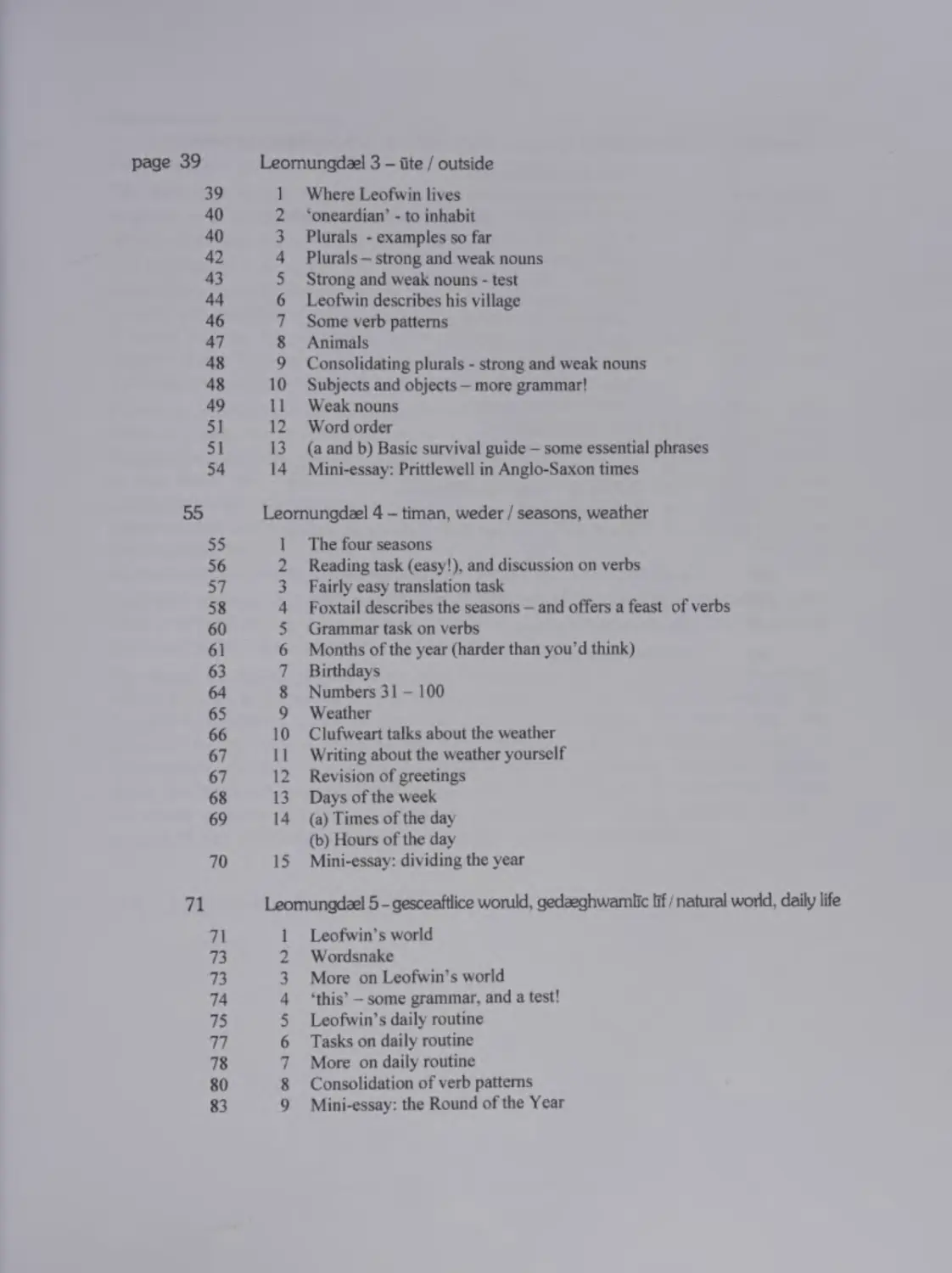

Going Back in time - New English to Old English

Language never stops changing! New words are being born all the time, while others fade away.

The way we pronounce words changes slowly over time as well, while more slowly still we alter

the rules of our grammar. How hard will it be to learn the English spoken here more than a

thousand years ago?

1800

If you could travel back in time 200 years, you’d be able to understand the English spoken here in

England without any difficulty, although a few of the sounds and words might be just a little

unfamiliar at first. Because of Britain’s Empire, English is already a global language, spoken in

North America, the Caribbean, India, Australia, parts of Africa and elsewhere.

1600

Another 200 years back: this is the language of Shakespeare. It’s recognizably English, but with

many unfamiliar words and expressions. Printing has helped to ‘standardize’ the language, and lots

of Greek and Latin words are being brought in which we take for granted in the 21° century.

However, many words and some of the grammar seem strange. The language of this period is called

‘Early Modern English’.

1400

Now we’re back to medieval times. Printing hasn’t been invented yet, so all writing is done by

hand. The thousands of French words which flooded into English after the Norman Conquest of

1066 are still settling in to the language. The language sounds very different, and without studying

it, you’d find many words unrecognizable. The language of these times is called ‘Middle English’.

1200

There are two different languages being spoken in England. Norman-French is the language spoken

by the king, the court, and the upper classes, because of the Norman Conquest. English is spoken

by the English people, with just a few words beginning to be adopted from French. These are the

last generations to speak alate form of ‘Old English’. For 21“ century English-speakers, it’s virtually

a foreign language.

1000

Another 200 years back in time: the Battle of Hastings hasn’t yet been fought. Old English is

spoken across the length and breadth of England. Because of the efforts of King Alfred the Great,

many literary and religious texts have been translated into English, and it has become a language

capable of expressing sophisticated thought. Trade and cultural links across the North Sea, and the

settlement of Vikings in the east and north is playing a part in simplifying Old English. This book is

set in this period, in the late 900s.

800

As we go ever further back in time, it starts to grow difficult to find surviving documents in Old

English. There are several different English-speaking kingdoms across the land, often at war with

each other.

600

The English at this time are still fighting with the people who were here before they arrived — the

Britons. They’ve been coming from across the North Sea for a hundred and fifty years or so: in

particular from the areas known today as Angeln, Saxony, Jutland and Frisia. These times have

8

since become known as the “Migration Period’. The native Britons speak a Celtic tongue similar to

Welsh, but their language and culture is being steadily overwhelmed by the Germanic newcomers.

The English rarely use writing, except in runes.

400

English speakers are here as settlers, many are ‘foederati’ invited over by the Romans to help

defend the shores of Britannia against pirate raids, in return for land. Britannia is still a Roman

province, its people are Britons, and the Roman ruling class speaks Latin. The English (Angles) are

one of many Germanic tribes living in mainland Europe — although there’s an intriguing possibility

that some Germanic tribes settled in Britain even before the arrival of the Romans

100

Tacitus, a Roman historian, is the first to mention the ‘Anglii’ (Angles), in a long list of Barbarian

tribes he describes in a book about Germany.

How do we know what OE sounded like?

Old English writers borrowed the Latin alphabet ‘ready-made’ after the arrival of Christianity, so

the values of the letters corresponded closely to what we know of later Latin pronunciation.

Comparison with modern languages like Dutch, Danish and German also helps. Medieval written

English gives further clues about how pronunciation changed over the centuries, and modern

English can sometimes be a good guide — but only sometimes! In the end we don’t know for sure —

and there’s still plenty of disagreement among scholars!

Regional Variation

There were several different dialects of Old English, just as there are today:

Northumbrian

All northern variations, north of the Humber. Viking influences here filtered southwards

from the 10” century.

Mercian

Now called the Midlands. West-Mercian later fell under the influence of the Wessex dialect,

while East-Mercian changed through Viking influence after becoming part of the Danelaw in

the 9 century.

West Saxon

Came to dominate South-Western and South-Central dialects of English. This is the favourite

dialect for most modern books dealing with the subject of old English — including this one!

Kentish

The basis of the South-Eastern dialect.

A Note on Old English Writing and Pronunciation

People were speaking Old English long before it was ever written down. Symbols called runes were used

from the 2nd century onwards, but usually only for short messages or inscriptions, for example on

possessions, monuments etc. Christian missionaries brought with them the Latin alphabet, and eventually

began to use its letters for the sounds of English. Where they couldn’t match English sounds to Latin letters,

they added new ones.

AF hancheNeem remeeleelat wile. kOup Wyuna eiattarty

i 0URLORIG PASE El WYMSV bia gd akOy akWeal onl oS Gong

Most letters are fairly easily recognizable — note the ‘i’ didn’t have a dot, whereas ‘y’ did. ‘g’, ‘s’ and ‘r’

need a little getting used to.

Letters in OE no longer used in NE

z ‘ash’ the ‘a’ sound as in ‘black’ (see long and short vowels, below).

6 ‘eth’ and b ‘thorn’ both make the ‘th’ sound. There’s a temptation to think that one is for the ‘voiced’

sound, (eg this) and the other for the ‘unvoiced ’sound, eg (think), but this isn’t the case. In fact, they’re

interchangeable.

Other letters

g can be pronounced as in NE, but also ‘ch’ as in ‘loch’, but lighter.

Annoyingly, it can often make the sound ‘y’, as in ‘yes’.

sc when used together, nearly always make the sound ‘sh’ as in NE ‘ship’.

j, V notusedinOE. q, kandz rarely used in OE.

w wasn’t used in OE: they used another letter instead called ‘wynn’ w, which looks like

a slightly squashed ‘p’. Modern text-books (including this one!) just use a w.

c often has the sound ‘ch’ as in NE ‘church’, but sometimes as in NE ‘cat’.

SHORT AND LONG VOWELS — approximate sounds

A little bar called a ‘macron’ over the letter is often used in

modern text-books to indicate long vowels

as in NE ‘cat’

as in NE ‘bun’, but tending towards ‘o’.

as in NE bed*

asinNE sit

as in NE ‘not’

as in NE ‘look’

as in French ‘tu’

between NE ‘there’ and NE ‘day’

as in NE ‘barn’

as in NE ‘bade’

as in NE ‘seat’

as in NE ‘note’

as in NE ‘luke’

as in French ‘tu’ but longer

SHORT AND LONG DIPHTHONGS (two-vowels together’)

ea asin NE ‘cat’ + neutral vowel*

éa &+a

eo two short vowels together

ie asin NE ‘sit’ + neutral vowel*

Kc

om

OpwFi

*At the end of a word, probably a ‘neutral vowel’, like the ‘er’ in ‘leader’.

10

How to use this book

The abbreviations OE for ‘Old English’, and NE for

“New English’, (Modern English) are used

throughout the book.

Listening tasks are shown like this

Go to www.asbooks.co.uk to listen

to or download spoken answers

Writing tasks are shown like this

e Work for short periods — about half an hour at a time.

e Test yourself often on vocabulary. Find a friend who’s also learning OE.

e Check the internet for audio and video clips. Speak OE out loud as often

as possible.

e Transcripts of the audio tracks and answers to all the exercises are

. written in full at the back of the book.

| There’s also a grammar reference guide, and a bi-lingual vocabulary section. ¢

11

Meet Leofwin!

Hello! My name is Leofwin and I live in the village of Prittewella, in the

south-east corner of the shire of Eastseaxe. We’ve lived here for many

generations, but not always. There are legends which tell how our folk

came from across the Great North Sea and fought against the Britons, who

occupied this land before. Some of their descendents are still here, but

they speak our language now, and do things our way.

Once there were people here called Romans, who built great cities and roads in stone: but now many of the

building are in ruins because our way of life is different from that of the Romans. They built the road from

Lundenwic to Colneceastre. To the east of Prittewella is the Sea, and to the south is the Temes, the greatest

river I’ve ever seen. Beyond that is Outland, but I’ve never been there. Ships sail up the Temes, sometimes

with goods from Outland to trade with us.

There are eight or nine families like mine living in Prittewella, each one with a wooden house and a few

outbuildings. There’s also the Thane, Godweard, who lives in the Hall, but more about him later. The village

used to be a little further down the hill in the olden days, but as the houses grew old and rotten, we just built

new ones further up.

My wife is called Golde, and we have two children, Clufweart (which means buttercup) and Foxtail. My

mother Elfgifu lives with us, but father died some time ago. Golde’s brother often comes to visit with news

of her family. We have a slave we call Spreculmuth, which means chatterbox, but he doesn’t say much at

all. He used to be a freeman like me but was caught stealing silver from the church. He was sentenced at

Lord Godweard’s court to be reduced to slavery, and Godweard gave him to me. I didn’t really want a slave

and his family, and he’s more trouble than he’s worth — but I couldn’t refuse my lord’s generosity. Our dog

is called Haleth, which means hero. He follows Foxtail and me everywhere.

I’m a ceorl, which means I’m a free man and the head of my family. We live by farming, like everyone in

Prittewella, and it can be hard work. I farm about forty acres of land (about 16 hectares) which in this part of

England is called a hide and is considered enough to support a large family.

We grow wheat, barley, rye and oats, and each family has its share of the big communal fields. In this way

everyone has a fair share of the best and the worst land. I share the meadow-land with the other families as

well: I keep a few sheep and goats there. The Thane owns the two village ploughs, and we all take turns to

borrow them.

In summer my pigs and cows stay in the nearby woodland which is common land; in the winter the pigs feed

on acorns and anything else they can find to eat. The woodland is an important source of fuel for all the

villagers. We collect fallen branches for fuel but trees on common land can only be cut down with the

approval of the other villagers.

We keep chickens next to the house, and Golde grows peas, beans, herbs and all sorts of other plants in the

garden for cooking, medicine, dying clothes and making ale. I rent some of my land to two poor men,

Shortban and Blerig and their families. They are able to grow enough food to live on but in return they work

for me two days every week, and supply me with part of what they grow. I let them build a cottage out in the

fields to live in, but it counts as my property, not theirs. They’re always trying to get out of things if I don’t

keep an eye on them.

We eat mainly bread, cheese, eggs, and vegetables. To this we add animals that I catch in traps, and birds we

shoot with a sling. The children gather fruit, nuts and berries from the woods when they’re in season. We call

that ‘the wild harvest’. When a family slaughters a pig or cow, they preserve the meat by smoking or salting

it: not even Fat Freda can eat a whole pig in a few days! We trade fish with the folks who live by the sea, and

honey with the bee-man who lives near the bridge. We drink mainly ale, which Golde makes, but there are

12

two wells which we can use for water, as well as the stream. Clufweart and Foxtail fetch water up to the

house in buckets every morning.

Godweard Thane owns the biggest farm in Prittewella. He is the only man rich enough to own horses. When

the eorl in Roccesforda needs fighting men, Godweard answers the call: he’s a warrior. He owns two mail

coats, a fine sword and a war-helmet. He helps protect us all in time of war and has the right to call me out to

help him, too, but luckily that hasn’t happened for a while. Nevertheless, I have to have a spear and a shield

just in case, as well as the knife (seax) I always carry. Lower-class people like Scortban and slaves aren’t

allowed to carry weapons.

There’s an Alderman called Byrhtnoth, who looks after all of Essex on behalf of Ethelred the King, but I’ve

never seen either of them.

Godweard helps sort out disputes in the village, and tries to make things run smoothly. He takes charge at the

monthly moot (gathering of freemen) which I have the right to attend. My land is Godweard’s gift to me,

which he renews every year, as long as I pay him rent and ensure that his horses are looked after and I work

on his field one day a week. The rent consists of regular deliveries of milk, cheese, ale, eggs, and many other

things, according to the season. He keeps some of this for himself, but passes some on to his lord the eorl in

Roccesforda. Sometimes I am paid with silver pennies when I sell things at the market in Roccesforda. If

Godweard agrees, I can pay him some or all of my rent with coins instead of produce.

North of the village, down the hill, there’s the stream we call the Pritta. There’s a wooden bridge across it,

and all the villagers help keep it in good order, though some need reminding of this obligation. The children

love to play down there. The lane south leads all the way to the mouth of the Temes where there’s another

settlement called Middeltuna. The people there live mainly by fishing and boat-building. Sometimes traders

beach there and we see things from far-off places. There are always fish hanging from racks, smelly nets and

piles of cockle-shells. As well as the two villages, there are some farmsteads dotted around the countryside.

We believe in Christ the Saviour, the Son of God who died to take away our sins. We worship in a wooden church

where Ealhstan the priest preaches on Sundays. Some bigger settlements have stone churches.

Many of the old customs and beliefs are still with us. We don’t forget the magical beings all around us who

live in our houses, in the woods, marshes and fields, underground and in the sea. Some wander among us at

times in the form of men or animals. Certain stones and trees are special to us, and although they may be

invisible, we feel the presence of elves, good and bad. The sun and the moon, and the wandering stars: to

some people these too are magical beings. Ghosts haunt the land, especially at night, and at certain times of

the year. There’s a woman in the village, Freda, a healer, who understands plant-lore and knows strong

magic: we sometimes go to her for help.

We bury our dead near the church, but close to the woods north of the stream, there’s a haunted place which

our ancestors used. Long ago, a king of Eastseaxe was buried here in a mound, and some say his ghost still

walks in time of danger. Those kings are long gone, and we are ruled now by our Alderman and by Ethelred,

king of all England.

In this book, you’ll find out all about these things: you’ll get to meet my family, find out how we live, and

share in some of the ups and downs of life in Prittewella. But mainly, you’ll learn my language: the language

that yours is descended from. I hope you enjoy it!

Wes 67 hal! Leofwin

13

leornungdeel 1: min cynn unit 1: my family

Ois is min

wif, golde

éala! ic hate

leofwin

éala!

leofwin is

min ceorl

and Ois is

foxtegele...

ic hate

clifweart,

and Gis is

min

brddor,

foxteegele

wesad gé

hale,

gehwa!

leofwin is tire feeder,

and golde is tire mddor

15

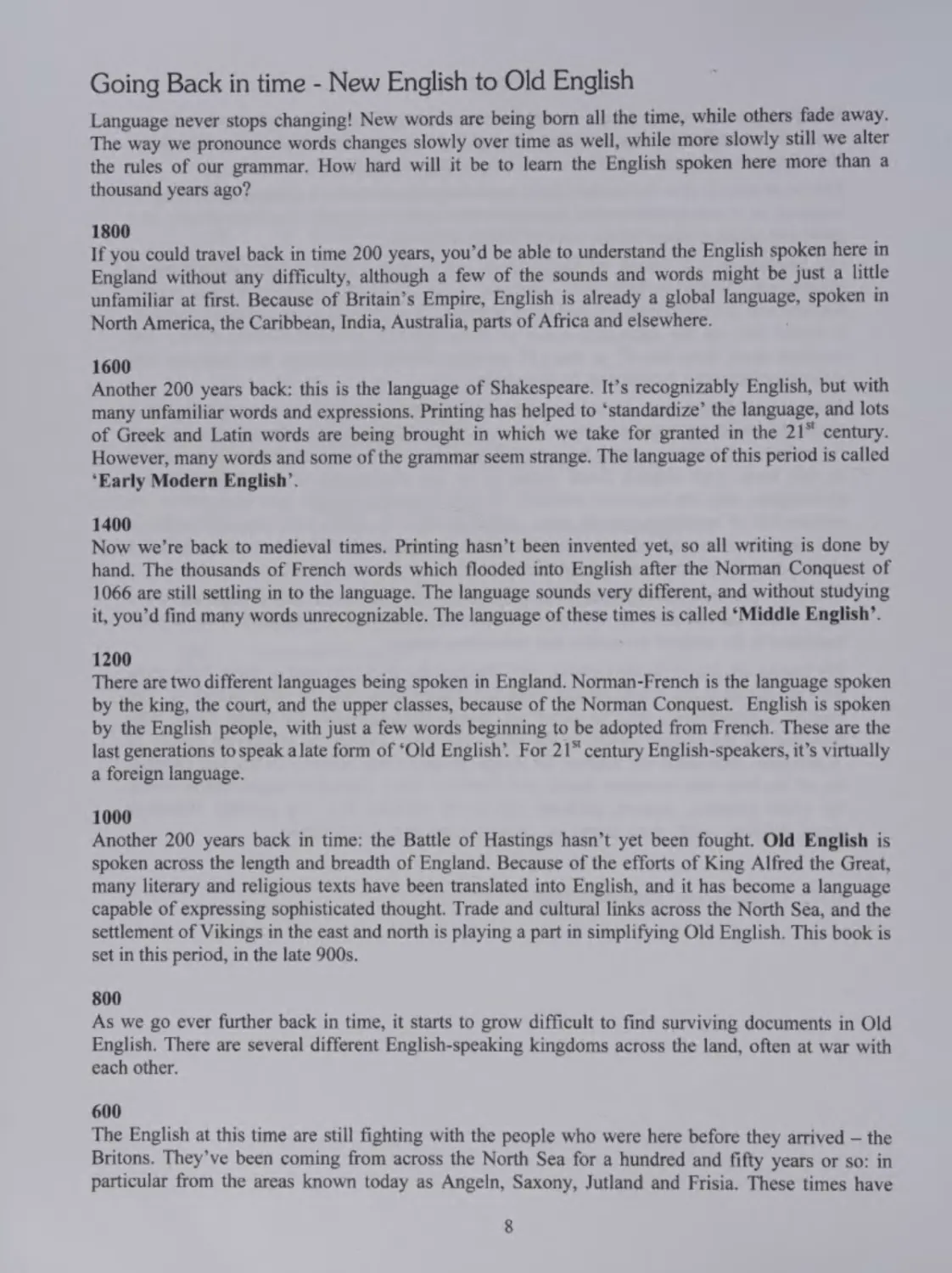

Leornungdel 1

“

2. Answer the questions - check on the next page for vocabulary if necessary:

3. Listen to the members of the family, and repeat what they say:

éala!! ic eom leofwin! ic eom 6ritig géar eald. golde is min wif. héo is nigon

and twentig géar eald. ic heebbe tii bearn, foxteegele and clifweart. foxtegele

is cnapa, and clifweart is meg6.

ala! ic eom golde! ic eom nigon and twentig géar eald. leofwin is min ceorl.

hé is Gritig géar eald. foxtegele and clifweart sind tire bearn.

ala! ic eom clifweart! ic eom tyn géar eald. ic habbe an brddor, foxtegele.

leofwin and golde sind mine ealdor. leofwin is wer, and golde is cwén.

éala! ic eom foxtegele! ic eom eahta géar eald. ic habbe sweostor, cliifweart.

leofwin is min feeder, and golde is min mGdor. wé habbaé éac hund. hé hated

heeled. saga ‘éala’, heeled!

WUF!

nb You may have noticed that when Clufweart speaks about her parents, she says

‘mine’, not ‘min’. The extra ‘e’ is an example of an ending, and OE is full of them!

They show what job a word is doing in a sentence. More of them later on.

16

min cynn my family

Vocabulary

wer

man

cwén

woman

cnapa

boy

mego |

girl

bam...

I’m called...

who?

this is...

husband

wife

mother

father

hello!

sunu

son

dohtor | daughter

sweostor | sister

brddor

brother

_wesao gé hale | be well

|| gehwa —s|._ everybody

ac.

also

Saga

say

bearn

children

~ealdor — parent(s)

|p Geis. | whois...

‘min, mine] my

our

éala! ic eom

tréow!*

4. Study the questions below, then listen to another family being interviewed. Give as

much information as you can, then check the answers at the back of the book.

==

«

ee

-

~

rm ="

Re ts

e-

Ne

“

-

hu hatest 6u?

What’s your name

hi eald eart 60?

How old are you?

eart 60 gehiwed?

Are you married?

hi hated din ceorl/wif?

What’s your husband/wife called?

hii eald is hé/héo?

How old is he/she?

heefst 60 bearn

Do you have children?

heefst 60 brddor/sweostor?

Do you have brothers/sisters?

géa, giese / na, nese

yes /no

and, ond / ac

and / but

o0dde

or

KS.

ee,

SENS

ae

SA

NS

eS

*yes, I’m a tree!

Wg

Leornungdel 1

5.You must know how to say ‘I am, you are, he/she is’ etc.

(*These are alternatives)

There are two words in OE for ‘you’.

The first (60) is singular — when you’re talking to one person.

The second (gé) is plural -when you’re talking to more than one person.

6. Here’s another set of words you met earlier.

Words that describe things you do are called verbs.

ic hate heled! WUF!

We’ve also seen a few examples of the verb ‘to have’:

but we’ll look at that one more closely in the next unit.

By the way, what did Foxtail just ask you? And how would you answer?

18

min cynn my family

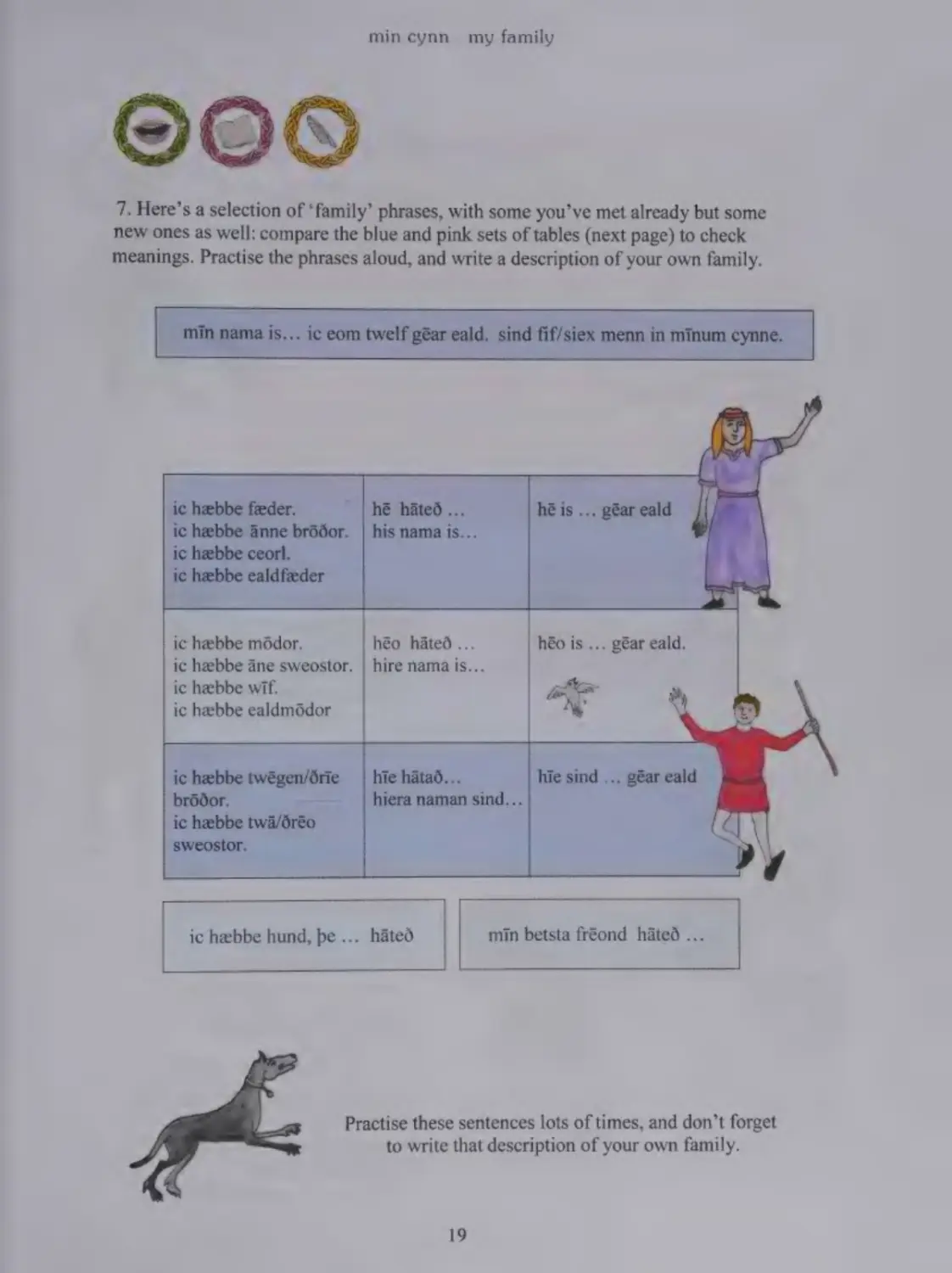

7. Here’s a selection of ‘family’ phrases, with some you’ve met already but some

new ones as well: compare the blue and pink sets of tables (next page) to check

meanings. Practise the phrases aloud, and write a description of your own family.

ic heebbe feeder. | hé hated...

ic heebbe Anne brddor. | his nama is...

ic heebbe ceorl.

ic haebbe ealdfeeder —

ic heebbe modor.

héo hated...

ic heebbe ane sweostor. | hire nama is...

ic heebbe wif.

ic haebbe ealdmodor

hie hatad...

hiera naman sind...

ic heebbe twégen/drie

brodor.

oe

ic heebbe twa/dréo

ssweostor,

ic heebbe hund, pe ...

min betsta fréond hated ...

Practise these sentences lots of times, and don’t forget

to write that description of your own family.

19

Leornungdel 1

My name is... I’m twelve years old. There are five/six people in my family.

Ihave a father —

He’s called

He is ... years old.

I have a brother.

his name is...

I have a husband.

I have a grand-father

Ihaveamother. — She’s called... She is ... years old

I have a sister.

her name is...

I have a wife.

I have a grand-mother

I have two/three

They’re called... They are... years old

brothers.

Their names are...

I have two/three sisters.

I have a dog who’s called...

Notice you don’t

normally need a

word in OE for ‘a’

(a dog, a mother etc)

My best friend is called...

8. Yes or no? Read the

following questions and

answer out loud with either a

‘oGa!

oa “na!”

*foxteegele is eald

*golde is wer

*Orie and eahta bé06 endlufon

*iire hund hated hzled

*leofwin and his cynn sind englisc

20

min cynn my family

9. Likes and dislikes. Who does Foxtail like and dislike?

Compare the two tables (blue, below, and pink, next page) as in Activity 7 above.

And you should be able to give your opinions about lots of people!

Elfgifu is Foxtail’s Grandmother, who’s a bit grumpy.

Spreculmuth is a slave who belongs to Leofwin.

ic lufie

ms Se

ne licad

ic hatie

minne hund

mé licad min mddor

mé élfgifu spreculmuo

minne feeder

mine mddor

|

ic lufie

minne brodor

ce

| god

ic hatie

mine sweostor

yfel

minne ceorl

snotor

mine wif

hé is

dysig

hé nis

leohtm6d

fordzm pe | héo is

mynewyroe

h&o nis

zoryht

min feeder

a.

mildelic

min modor

|

unmildelic

mé licad min brddor

oo

gedyldig

ne licad mé | min sweostor

ungedyldig

min ceorl

:

min wif

21

I love

I hate

I like

I don’t like

my father

my mother

my brother

my sister

my

husband

my wife

my father

my mother

my brother

my sister

my

husband

my wife

Now put the following into OE:

a) I like my brother because he’s good.

b) I hate my sister because she’s bad

c) Ilove my mother because she’s kind.

d) I don’t like my husband because he’s quite boring

e) I don’t like my father because he’s very stupid.

ic heebbe sunu. hé hated leofwin. ic lufie leofwin,

fordzm 6é hé is min sunu. ic hate heled, ford#m dé hé

is yfel and dysig.

Leornungdel 1

he is

he isn’t

she is

she isn’t

because

good

bad

clever

stupid

funny

interesting

boring

kind

unkind

patient

impatient

very

very

very

quite

ic lufie minne brddor ford#m pe hé is leohtmod

and géd, ac hé is éac dysig and hé stincd!

ic hebbe wif. héo hated nigonfingras. mé licad

nigonfingras fordzém 6é héo is snotor and mildelic.

Le

Did you notice

the neat way of

saying ‘isn’t’?

Can you add some opinions like these to your description from activity 7?

Here are two examples:

min cynn my family

10. Numbers 1-30!

Listen and repeat. Two things to notice — firstly, ‘two’ and ‘three’ change

depending on whether you’re referring to a ‘he’, a ‘she’ or an ‘it’!

Secondly, the tens and digits are the other way round in 21-29. That explains

the blackbird! Counting out loud is a really good way to practise pronunciation,

as well as learning the numbers. There’!I be more numbers later on.

an

endleofon, endlufon

twégen (fem: twa, neuter: ti)

twelf

Ory, Orie (fem + neuter: dreo)

dréotiene

f€ower

feowertiene

fif

fiftiene

Siex, SYX

siextiene

seofon

seofontiene

eahta

eahtatiene

nigon

nigontiene

tyn, tien

twentig

an and twentig

-

siex and twentig

twégen andtwentig (>

seofon and twentig

thrie and twentig

FS.

eahta and twentig

féower andtwentig

42 -15m

nigon and twentig

fif and twentig

oritig

Can you do the following sums?

(nb ‘bé00’ is another way of saying ‘are’)

* An and an béo0...

* siextiene and eahta béod...

* Orie and seofon béo6...

* fif and endleofon bé06...

* nigon and féower bé00...

* fif and twentig and twégen béo0...

ps)

Leornungdel 1

9% 11. Here’s a fuller list of family vocabulary. Notice that each word has a letter in

x y brackets next to it. (m) shows that the word is masculine. (f) shows it’s feminine. (n)

“@egs” shows it’s neuter—neither masculine nor feminine, but just an ‘it’.

This idea is called gender. It may seem obvious, but if you check below carefully, there are a

few surprises! Can you find which ones?

In unit 2, you’ll find a lot more surprises about masculine, feminine and neuter. Can you also

find where we get the NE words woman, queen, knight, knave, wench...

cynn (n) —

feeder (m)

mOdor (f)

brddor (m)

sweostor (f)

sunu (m), eafora (m), magu (m)

dohtor (f)

wif (n), cwén (f), om (m)

ceorl (m), wer (m)

ealdfeeder (m)

ealdmddor (f)

nefa (m)

nefene (f), nift (f)

éam (m)

feedera (m)

mddrige (f)

fade (f)

swustersunu (m), brodorsunu (m)

swusterdohtor (f), brodordohtor (f)

cradolcild (n) bearn (n)

cnapa (m)

cwén (f), maegd (f) m&den (n) wencel (n)

bearn (n), cild (n), lytling (m)

cniht (m)

mon(m), guma(m), wer (m), secg (m)

wif (n) cwén (f)

hlaford (m), dryhten (m)

hléfdige (f), ides (f)

fréond (m), wine (m)

family

father

mother

brother

sister

son

daughter

wife

husband

grand-father

grand-mother

grand-son

grand-daughter

(maternal) uncle

(paternal) uncle

(maternal) aunt

(paternal) aunt

nephew

niece

and werewolf?!

min cynn my family

12. Read Foxtail’s account of his family and translate it into NE:

éala! ic hate foxteegel. ic eom eahta géar eald. ic eom wel snotor!

ic heebbe ane sweostor, be clifweart hated. me licad cliifweart

ford&m de héo is leohtméd and mildelic.

mé licad €ac mine ealdor. hie hatad leofwin and golde. ic lufie

minne feeder fordéém pe hé is leohtmid, and mine modor

forédém pe héo is gedyldig.

ic heebbe €ac hund. hé hated haled, and hé is d¥sig, ac hé

is min betsta fréond.

min ealdmGdor is féower and siextig gear eald. hire

nama is &lfgifu. ne licad mé min ealdmodor forb#m

be héo is unmildelic and yfel.

13. Anglo-Saxon Families

The father was the head of the family in Anglo-Saxon England, and the spear propped up by the

door symbolised his role as protector. In fact, the father’s side of the family was called the

‘sperehealf’, while the mother’s side was called the ‘spinelhealf’. The spindle symbolised her

social role in the family — the spinner and weaver of caring relationships. The latch keys she wore

hanging from her waist band showed she was in charge of house and home. The possessions found

in men’s and women’s graves confirm the link with spears, spindles and keys.

The father would likely have had more to do with teaching his children outdoor skills while the

mother taught indoor skills. The mother’s brother (‘eam’) traditionally had a special caring

relationship with his nephews — this probably included teaching and spoiling them.

OE has many more words for different family relatives than NE, which shows how important the

idea of ‘family’ was for them. If you weren’t very good at remembering all the complexities,

though, you could call any relative ‘brédor’ or “sweostor’.

You might have ‘stéop-’ relatives, if your own parents were dead, or ‘foster-’ parents, if your real

parents had given you away for some reason.

There were almost certainly four or five people in the average family — records from the year 1200

suggest 4.68*. Other relatives, then as now, of course, may have ‘lived in’, as Leofwin’s mother

does. It seems likely that there was an equivalent in Old English to ‘Mum/Dad, Mummy/Daddy,

but nothing is recorded. It’s tempting to suggest something like ‘muma’ and ‘dada’, but it’s a

temptation that has to be resisted!

Cynn were family members. People outside the family, but whose name, family and origin were

known would count as ‘ey66’. Nearly verybody in the village and the surrounding area would

count in this group. Together, your family and friends were “cy60’and cynn’, or “kith and kin’.

People you didn’t know could become ‘cy60’ or a “fréond’ or guest after they’d explained exactly

who they were. Otherwise, strangers were seen as little different from enemies or slaves — “Oéow’.

*quoted in ‘Domesday Quest’, Michael Wood, BBC books, 1986

Thanks also to AC Haymes, ‘Anglo-Saxon Kinship’, in ‘Widowinde’, Winter 1998

25

leornungdeel 2: min hts

unit 2: my house

éala! ic eom leofwin.

ic onerdie tin be

hated prittewella

sind siex

006e seofon hiis

bid duru,

f€ower weallas

and hrof

golde hef6 webbéam,

ac hé nis hér

Ois is se heor6 and Ozt

alfeet. her golde bzecd

golde and ic slépa6 hér.

Ois is Ure bedd

we wascao tis widitan.

spreculmi6 and his

cynn oneardiad det

lytele his. hie sind

péowas

...and mddor (élfgifu)

slép6 hér. mddor is eald

6a bearn

slépad hér...

2

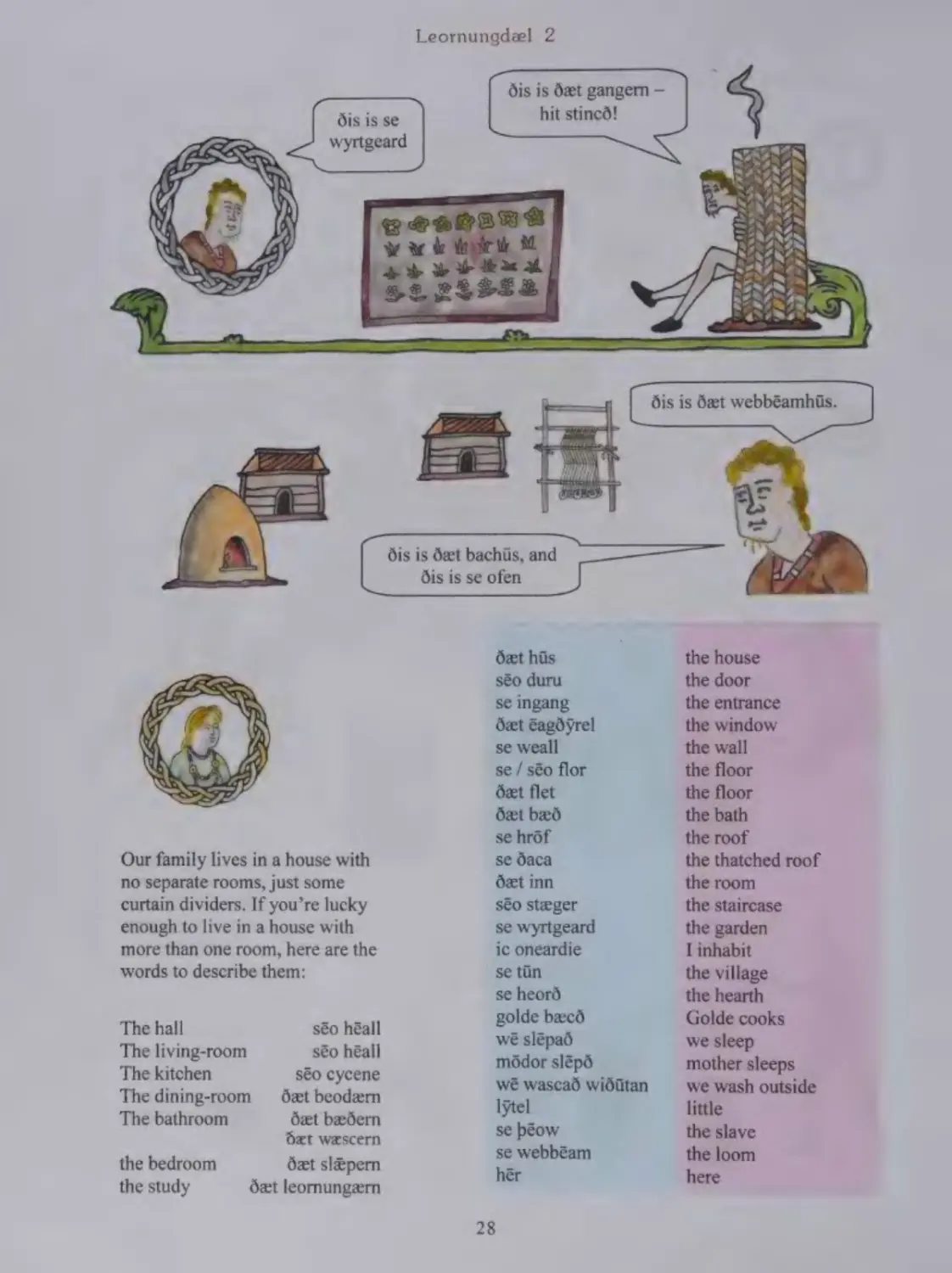

Our family lives in a house with

no separate rooms, just some

curtain dividers. If you’re lucky

enough to live in a house with

more than one room, here are the

words to describe them:

The hall

séo héall

The living-room

sto héall

The kitchen

séo cycene

The dining-room dzt beodern

The bathroom

Ozet beedern

Oat wescern

the bedroom

det slépern

the study

det leornungzern

Gis is se

wyrtgeard

Leornungdeel 2

hit stincd!

Fr WN

Wn et

BED |)

|4

fia.ramcomrene

Gis is Ozet bachts, and

Ois is se Ofen

Ozet hiis

séo duru

se ingang

det Eagdyrel

se weall

se / séo flor

Ozet flet

Ozt bed

se hrof

se daca

Ozet inn

séo steeger

se wyrtgeard

ic oneardie

se tin

se heord

golde beecd

wé slépad

mddor slépd

wé wascao widitan

lytel

se bow

se webbéam

hér

28

Gis is det gangern —

the house

the door

the entrance

the window

the wall

the floor

the floor

the bath

the roof

the thatched roof

the room

the staircase

the garden

I inhabit

the village

the hearth

Golde cooks

we sleep

mother sleeps

we wash outside

little

the slave

the loom

here

min his my house

Sw

giv)

\‘

Ozt spere

Leornungdel 2

3, Gender

We first looked at this in unit 1. Did you notice in the lists above that there seem to be

THREE words for ‘the’? This is because each gender has its own word for ‘the’.

Masculine - se

These are boys, men, and many things we think of as ‘it’ (neuter) in NE.

Feminine - séo

These are girls, women, and many things we think of as ‘it’ (neuter) in NE.

We still have this idea in NE, with words like ‘he’, ‘she’, and ‘it’, but OE can use

gender in a rather surprising way. Many ‘things’ we think of as neuter, like the door,

or the garden, can be feminine or masculine. There are some surprises with people, too

- children are neuter in OE! You just have to get used to this idea. With every new

word you learn, you must remember if it’s masculine (m), feminine (f) or neuter (n).

Make a start by learning all the household things from the previous page.

Make three columns, and label them masculine,

feminine and neuter. Put all the masculine ones in the

left-hand column, the feminine ones in the middle

column, and the neuter ones in the right-hand column.

There’s a fourth word, 64, for ‘the’, when you’re talking about more than one of something -

‘plural’. Fortunately, 64 works for masculine, feminine and neuter words. Unfortunately, OE

doesn’t just put an ‘s’ on the end of a word to show when we mean more than one — but that’s a

problem for another unit.

Oh, what did all those words mean? Here are the same words in New

English — but mixed up! Up to you to work them out: bed, child,

woman, garden, bench, father, wool-basket, loaf, table, sister, cup, jug,

fire, door, cooking-pot, village.

30

ic hebbe

ic hebbe

ic eom

min his my house

lang / scort

I'm

fett / dynne

eald / geong

blachléor, cymlic / unfeeger

stib / unmihtig

englisc / denise / bryttisc

briin hér (n)

feeger h&r / swéart hér

blac hér / hwit hér

greg her

scort hér / lang h#r

beard (m) / cenep (m)

I have

héwen / briin /

Ihave

grég / gréne éagan (n pl)

snotor / dysig

I’m

mildelic / unmildelic

smeorcsum / hefigm6d

gemad / wod

idelgeorn

scéoh / beald

frec / gredig

giernendlic / wilsumlic

4. Listen to the phrases below describing people’s looks and

characters. Practise repeating them.

tall / short

fat / thin

old / young

pretty / ugly

strong / weak

English / Danish / British

brown hair

fair or blond hair / dark hair

black hair / white hair

grey hair

short hair / long hair

beard / moustache

blue / brown /

grey / green eyes

clever / stupid

kind / unkind

funny/ serious

mad

lazy

shy / outgoing

greedy

sexy

5. Now listen to Golde describing herself and her family, then answer the

questions:

1. Is Golde good-looking?

2. Describe her hair.

3. Who has fair hair and blue eyes?

4. Who is greedy and unkind?

5. Who is strong and clever?

6. Describe Foxtail’s character.

6. You should now be able to use the grid to describe yourself. If possible,

describe one or two other members of your family as well!

Remember that you can improve

your description if you use some

of these words from unit 1:

Sa

Leornungdeel 2

7. Read Leofwin’s description of the slave Spreculmuth

and his family, then answer the questions:

spreculmi6 is min déow. hé is scort and dynne,

and hé is eald. hé hef6 lang, grég hér, and

gréne Eagan. hé is swibe dysig and idelgeorn.

his wif is Eac scort and 6ynne, ac héo is sumes

snotor. hire nama is nigonfingras, fordzm de

héo hef6 ane* nigon fingras.

spreculmip and nigonfingras habbad feower

bearn: 6réo mzegé and anne cnapa. ba mzegd habbad sweart hér, and se

cnapa heef6 briin hér. pa bearn sind unmihtig, scéoh and dynne.

*°ane’ here means ‘only’.

1. What is the OE word for ‘slave’? — 4. Who has black hair?

2. Describe Spreculmuth’s character. 5. How are the children’s characters described?

3. What’s his wife’s disability?

6. Who’s described as quite clever?

godweard

1. ic heebbe

2. ic eom swide

3. ic eom geong,

4. ic eom pynne

greg hér, and ic

feett, and ic heebbe

and ic hebbe lang,

and ic heebbe

eom sumes feett

feeger hér

feeger hér

beard and cenep

eye

min his my house

9. Listen, then answer the questions:

hér cym6 mddor!

ic doncie 6é, hit

gx0 wel, ac ic

eom hungrig!

hwér is

claifweart?

mddor! gddne

mergen! hu g&®6

hit todeg?

giese,

ealdmdodor.

hér is hlaf

ic doncie bé

éala, clifweart.

gif mé hlaf,

ic bidde pé

ic sarie, mOdor, wé nabbad ciese

godne mergen, ealdmddor! hér is se ciese!

33

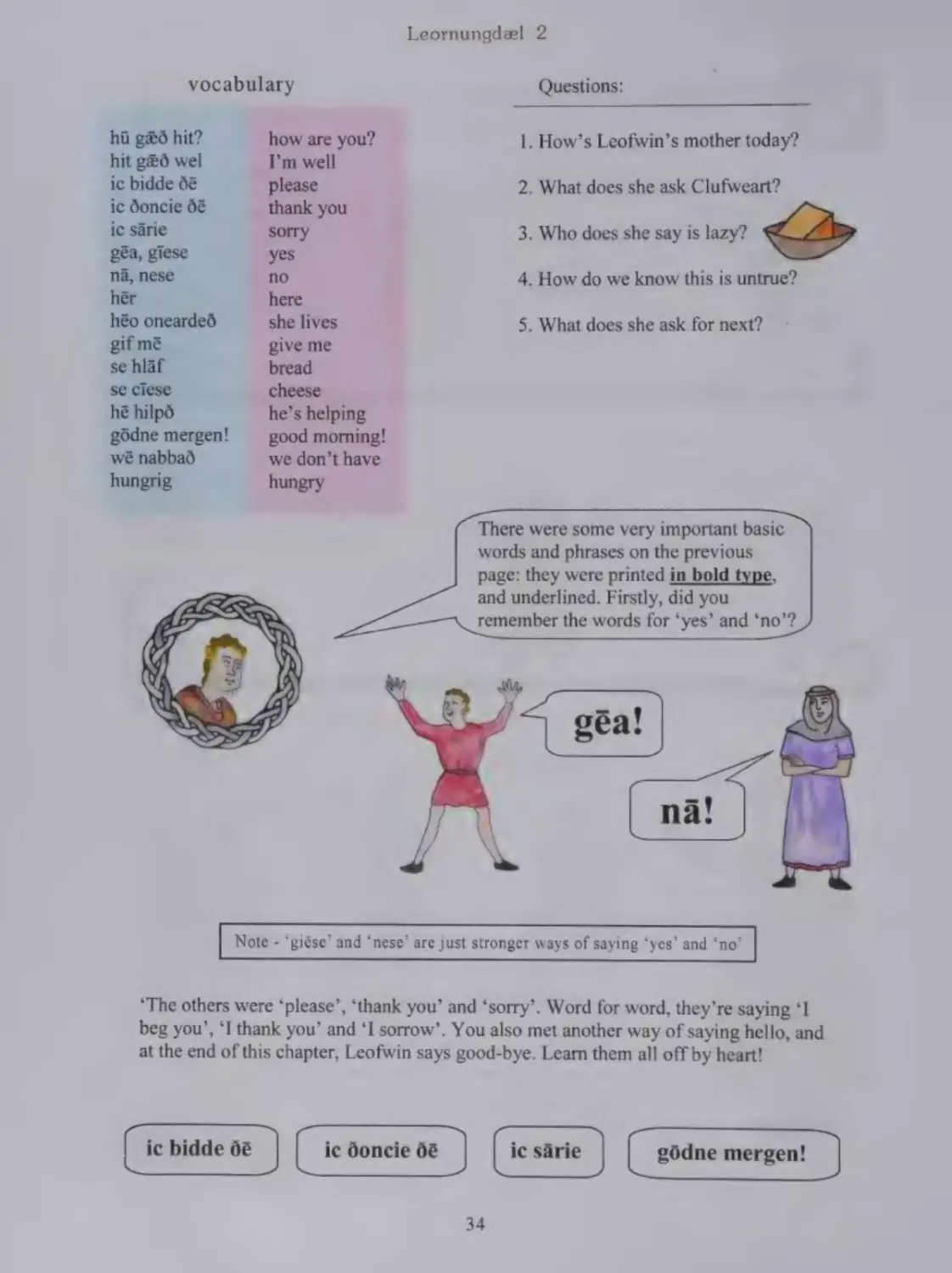

vocabulary

hi go hit?

how are you?

hit go wel

I’m well

ic bidde dé

please

ic doncie dé

thank you

ic sarie

sorry

géa, giese

yes

na, nese

no

hér

here

héo onearded

she lives

gif mé

give me

se hlaf

bread

se clese

cheese

hé hilpd

he’s helping

godne mergen! good morning!

we nabbad

we don’t have

hungrig

hungry

Note - ‘giése’ and ‘nese’ are just stronger ways of saying ‘yes’ and ‘no’

Leornungdel 2

Questions:

1. How’s Leofwin’s mother today?

2. What does she ask Clufweart?

3. Who does she say is lazy? <a>

4. How do we know this is untrue?

5. What does she ask for next?

There were some very important basic

words and phrases on the previous

page: they were printed in bold type,

and underlined. Firstly, did you

remember the words for ‘yes’ and ‘no’?

‘The others were ‘please’, ‘thank you’ and ‘sorry’. Word for word, they’re saying ‘I

beg you’, ‘I thank you’ and ‘I sorrow’. You also met another way of saying hello, and

at the end of this chapter, Leofwin says good-bye. Learn them all off by heart!

|icbidde 0é | icdoncie 6é

ic sarie

godne mergen!

34

béon

TO BE

ic béo

Iam

6i bist

you are

hé, héo, hit bid

he, she, it is

we bé06

we are

gé béod

you are

hie béod

they are

habban

TO HAVE

ic heebbe

I have

60 hefst

you have

hé, héo, hit hefd he,she,it has

we habbad

we have

gé habbad

you have

hie habbad

they have

min his my house

10. BEON

This is very much like ‘wesan’, but it suggests ‘being’

in a more permanent way than ‘wesan’ does. Use it

for sentences like ‘ the sun is yellow’, or ‘Clufweart is

a girl’. Use ‘wesan’ for sentences like ‘Golde is happy

today’, or ‘Foxtail is hungry’. As you probably

realised, NE has mixed these two verbs up together.

spere bid scearp!

11. HABBAN

This is the verb ‘to have’, and the family used it in unit

one. Like all three verbs we’ve seen so far, you’ll need

to use it constantly, so learn it off by heart!

ic hebbe wif, modor

and ti bearn

You need to know how verbs work, because without them you just can’t make a sentence, and

the language falls apart. The ‘title’ at the top of each ‘verb-box’ is called the infinitive — a

technical term that will be useful as you go through the book. There are more verbs to learn in

Chapter three, and a detailed study in Chapter four.

33

Leornungdeel 2

listen and repeat

12. HWILC HIW? (what colour?)

blac, sweart

hwit

read

h&wen*

séo niht bid sweart

snaw bid hwit

bléd bi6d réad

heofon bid h&wenu

fealu, geolu

gréne

greg

briin / dunn

séo sunne bid geolu

rdsen

eppelfealu / geoluréad

basuréadan

blac (=pale)

sméras béo6 rdsene setlgang bid geoluréada

winbergan béod

gast bid blac

basuréadana

vocabulary

Now answer the questions:

wonn, dimm dark

deorc, mirce dark

léaf bid...

asce bid...

feeger

fair or blond |

swin bid...

com bid

déag(f)

colour

fyr bid...

wudu bid._

bl&o (n)

colour

eorpbergan béo00... mist bid...

gylden

golden

molde bid...

plyme bi...

fealu

also yellow-brown

wull bid...

brim in sumor bi6...

or even dark!

don’t worry about the endings

etl

ue.

setlgang (m) ee

on some of the adjectives — yet!

**héwen’ can also be any combination of grey-green-blue

36

min his my house

vocabulary

more vocabulary

niht (f)

night

swin (n)

pig

snaw (m)

snow

fyr (n)

fire

blod (n)

blood

eordberge (f)

strawberry

heofon (m,f)

sky

molde (f)

the earth

sunne (f)

sun

wull (f)

wool

wolcen (n plural)

clouds

asce (f)

ash

gers (n)

grass

corn (n)

com

winbergan (fplural)

grapes

wudu (m)

wood

hara (m)

hare

mist (m)

mist

sméras (m plural)

lips

plyme (f)

plum

gast (m)

ghost

brim (n)

sea

léaf (n)

leaf

sumor (m)

summer

I live in Prittewella

This is the kitchen.

Foxtail has short, fair hair and brown eyes.

The sea in winter* is grey.

Clufweart is very hungry.

Where is the broom?

The bench is here!

Spreculmuth has four children.

The sky is pale today.

. Thank you — the cheese is good!

=eeSe2eeeee

*same word in OE!

14.

Have you noticed in this unit that the ‘thorn’ letter (p)

has been used as well as the ‘eth’ letter (6): they both

make the sound we represent in NE by ‘th’

fér 60 wel! (good-bye!)

x

Leornungdeel 2

15. Farmsteads, villages and towns

Leofwin’s house

No Anglo-Saxon houses survive! But traces like postholes in the ground show their size and shape.

They were squared off, and typically about 30ft x 15ft (10m x 5m). There’s evidence for wooden

floors, with a cavity underneath, possibly for storage.

Walls were built either with upright planks slotted together, or by ‘wattle and daub’. Most houses

probably had windows and wooden shutters. Glass was used in buildings belonging to the Church

but only the very well-off could afford it. There was a central hearth for warmth and cooking, but

chimneys did not appear until a long time after Leofwin’s time: the smoke simply seeped out

through the thatch.

There may have been an ‘upstairs’ in Leofwin’s house, possibly a floor at each end reached by a

ladder. Some beds were probably much less sophisticated than the drawings in this chapter show:

perhaps a cloth bag stuffed with wool, with blankets or fleeces on top. There was probably very little

furniture: perhaps a trestle-table, a pair of benches, a chest, baskets, and some shelves. The thatched

roof would be smoky and soot-blackened on the inside, ideal for curing meat.

Outside, there might be a number of smaller buildings associated with the houses: a midden or loo,

sheds for tools and storing food, shelter for livestock. Water had to be brought daily in buckets from the

nearest stream or well. After dark, candles or the fire gave the family’s only light.

Leofwin’s village

Archaeology shows houses grouped together into villages, typically of up to ten families — ‘a tithing’.

Most villages had a little wooden church, but Prittewella may have had a church built at least partly

of stone.

Farmsteads

The tradition of free-standing farms dates from from pre-Roman times, through the Roman

occupation, into Saxon and Medieval times, to the present day. There were probably a handful of

scattered farmsteads within a hour’s walk of Prittewella.

Roman towns

Towns depend on trade and money to survive. After the Romans left Britain, it seems that no new

coinage was minted at first, and partly for that reason the great towns and cities fell into decline. With

the arrival of the English, ports and towns in eastern England thrived as North Sea trade grew. The

nearest towns to Leofwin were Caesaromagus, which the English called Celmeresforda, and

Camulodunum, which they re-named Colneceastre. Even Londinium, known to the English as

Lundenwic, went into decline for a while.* In the time of King Alfred, London grew with new

development to the west of the old city.

Early English towns

From the 700’s onwards, English kings began minting coinage. With improved trade, a growing

population and a more sophisticated economy, towns began to grow. In the late 800’s, spurred on

by the need for defence against the Danes, King Alfred ordered the building of defences for

strategic towns. The security this gave attracted traders and boosted economic activity. By

Leofwin’s time English towns where thriving and the country was one of the richest in Europe. By

today’s standards most Anglo-Saxon towns and villages were tiny,** but nearly all of them have

survived, with something like their Anglo-Saxon names, into the 21‘ century.

* Chelmsford, Colchester and London.

** The population of England was about one thirtieth of today’s!

38

leornungdel 3: ite

unit 3: outside

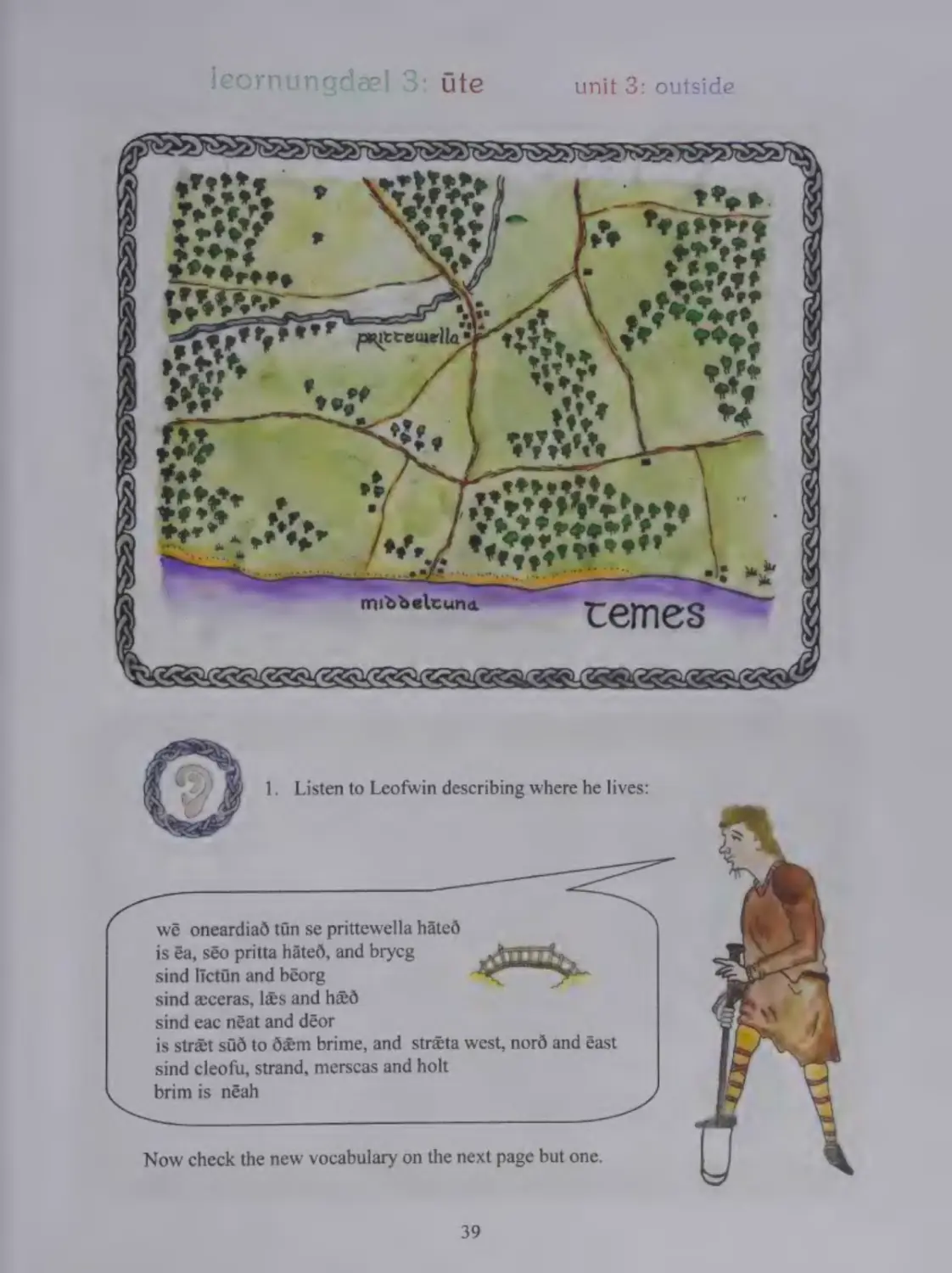

we oneardia6 tin se prittewella hated

is Ga, s€o pritta hated, and brycg

sind lictiin and béorg

.

sind zceras, l&s and h#dé

sind eac néat and déor

is str#t sud to 6&m brime, and strz&ta west, nord and éast

sind cleofu, strand, merscas and holt

brim is néah

Now check the new vocabulary on the next page but one.

39

leornungdel 3

2. The verb ‘to live in’:

Here’s the verb ‘to live in’, or

‘to inhabit’. I used itjust now.

oneardian

TO INHABIT

ic oneardie —

60 oneardast

hé, héo, hit oneardad.

wé oneardiad

I eeeee

Wit ial spat

ge oneardiad

we oneardiad prittewella.

hie _oneardiad

dis wyrm oneardad 64 moldan!*

* 64 moldan = the earth

noro

north

sid

south

west

west

éast

east

3. You can’t get far in a language without having to talk

about more than one of something (‘plurals’). Leofwin

mentioned fields, pastures roads, and a few other things in

section | above.

NE usually adds an ‘s’ to express this idea, but there are

some serious and very peculiar exceptions! (man/men,

child/children, ox/oxen, woman/women, fish/ fish,

tooth/teeth etc.). This is because we still haven’t completely

got rid of the rather complicated rules that English used to

have with plurals.

The vocabulary list below gives words used so far in this

chapter, but adds the plural form as well. Can you work out

any patterns?

ONE / MORE THAN ONE

se tin(m) 64 tiinas

séoea(f) da6€a

sto brycg(f) 6a brycga

se lictin(m) 68 lictiinas

se béorg(m) 6a béorgas

bet brim(n) 64 brimu

se strand(m) 04 strand

-stostret(f) 64 str&ta

pet clif(n) da cleofu

se mersc(m) 6a merscas

se ecer(m) 6a eceras

stolés(f) 6al&s

pet néat(n) 68 néat

petholt(n) 6a holt

sehed(m) 6a h&d6as

se wyrm 068 wyrmas

pet déor 64 déor

ute outside

ONE / MORE THAN ONE

the village the villages

the fiver the rivers

the bridge _ the bridges

the graveyard _ the graveyards

the barrow _ the barrows

the sea _ the seas

the beach the beaches

the road __the roads

the cliff the cliffs

the marsh _ the marshes

the field —_the fields

the pasture —_the pastures

the (farm) animal _the animals

the wood the woods

the heathland _ the heathlands

the worm __ the worms

the (wild) animal _ the animals

*What did Godweard just say

about barrows and graveyards?

eala! ic eom

godweard

degn. dis is

se béorg,

and Gis is se

lictiin.

ne licad mé

béorgas and

lictiinas —

dzr sind

gastas!

Here’s some of the vocabulary we’ve already learned in chapters one and two, but this time

with their plurals. Study them very carefully one by one: are any patterns emerging yet?

ONE / MORE THAN ONE

se broéor 6a brddor

séo sweostor 64 sweostor

séocweén 6a cwéne

se wer 06a weras

secnapa 0a cnapa

stomegd 6a megda

pet bearn 06a bearn

Set wif da wif

dethis 64 his

séo duru. 06a dura

det Gagdyrel 64 Eagdz&rel

se weall 6a weallas

det bedd 64 bedd

se webbéam 6a webbéamas

Ozt spere 6a speru

se crocca 06Aacroccan

det leaf 64 léaf

ONE / MORE THAN ONE

the brother the brothers

the sister __ the sisters

the woman the women

the man the men

the boy _ the boys

the girl __the girls

the child — the children

the wife the wives

the house __ the houses

the door _ the doors

the window _ the windows

the wall the walls —

the bed the beds

the loom the looms

the spear __ the spears

the pot __the pots

the leaf the leaves

4]

OE plurals are a bit like

this entangled man — but

the next page should

untangle things for you!

leornungdel 3

4. Nouns and Plurals

A ‘noun’ is the name given to a thing, whether it’s person, like Leofwin or Clufweart, a thing .

like a house or a bed, an animal like a dog or a cat, or even a quality like hunger, happiness or pride.

There are two very common patterns of nouns, called ‘strong’ and ‘weak’. There are several

less common ones, too, but for the moment, they’re all listed together in the ‘others’ box.

Grammar-books call all these patterns ‘declensions’.

STRONG NOUNS

masculine masculine

feminine

feminine

neuter

neuter

singular . plural

singular

plural

singular

plural

se wer

0a wéras

séo stret 0a streta

se tun

6a tiinas

séo duru 6a dura

se lictiin 64 lictiinas

se mersc 6a merscas

se eecer

0a eeceras

se hed

6a h&das

se wyrm 6a wyrmas

se weall 6a weallas

se webbéam 064 webbéamas

Plurals end with -as

Plurals end with -a

WEAK NOUNS

ae9

masculine

masculine

feminine

feminine

neuter

neuter

singular

plural

singular

plural

singular

plural

se crocca

0a croccan

séo bune

6a bunan

Most singulars end with -a Most singulars end with —e

Plurals end with -an

Plurals end with -an

42

ute outside

OTHERS

These are a bit unpredictable, so we call them ‘irregular’ for the time being.

masculine

masculine

feminine

feminine

neuter

neuter

singular

plural

singular

plural

singular

plural

se €a

0a Ga

séo les

0a l&s

se brycg

6a brycga

séo cwén 0a cwéne

se cnapa

0a cnapa

séo megd 0a megoa

5. Now it’s your turn. Fill in the gaps, looking up any new words in the vocabulary

section at the back.

>: STRONG NOUNS

masculine masculine

feminine

feminine

neuter

neuter

singular

plural

singular

plural

singular

plural

se stdl

OB nas:

séo byden 04....

se binn

Oa:

séo hleder

Ode.

se camb

0a...

se béam

Dacia

byden=bucket

Why are they called

strong and weak nouns?

As time went by, some

of the complicated OE

rules about nouns died

away. Words which

adapted the quickest are

weak nouns, while

words which people

WEAK NOUNS

masculine

masculine

feminine

feminine

ied Ge

singular

plural

singular

plural

didn’t like to change

are called ‘strong’.

se besma

Ona.

séo meatte

0a ...

43

leornungdel 3

6. Read and listen to Leofwin’s account of Prittewella below, then find

the exact OE phrases which correspond to the NE ones numbered 1-9:

on prittewella, sind eahta odd6e nigon cynn.

se degn hated godweard. hé hef6 wif and ti bearn. his dohtor hated

agata. hé hefd eac préo odde feower hors, twa sylh, gréat his and micel

land. hé heef scop, se brada hated. brada singed sangas for us.

se préost hated ealhstan. hé gen&osaé tis hwilum. hé hefd diacon and

lytele cirican on prittewella. hé h&l6 folc and bringed spell of ttan.

we growad fodan swa hwéte, bere, atan and béana.

wé healdad néat, swa cy, swin, scéap, get and hennan.

we healdaé séweard wid wicingum.*

*We’ll study this ‘um’ ending in Book 2

He has a deacon

8 He has a wife and two children

He has a story-teller

1 Brada sings songs

2 He visits us

3 He heals people

4 He brings news

5 We grow food

6 We keep animals

7

9

séosulh _—a sylh

OTHER

the plough the ploughs

se scop pa scopas STRONG

the story-teller -tellers

se préost papréostas STRONG

the priest

the priests

sediacon padiaconas STRONG

the deacon the deacons

séo cirice pa cirican WEAK

the church the churches

se hweete

STRONG

the wheat

se bere

STRONG

the barley

pa atan

WEAK

the oats

séo béan _—pa béana STRONG

the bean

the beans

pet néat pa néat

STRONG

the animal the animals

séo cul pa cy

OTHER

the cow

the cows

petswin baswin

STRONG

the pig

the pigs

pet scéap a scéap STRONG

the sheep

the sheep

se gat pa get

OTHER

the goat

the goats

séohenn _—pa hennan WEAK

the hen

the hens

pet hors pa hors

STRONG

the horse

the horses

se wicing pbawicingas STRONG

the Viking the Vikings

pet spell a spell

STRONG

the news

se foda pa fodan WEAK

the food

44

ute outside

€ala! ic eom ealhstan préost and

pis is min cirice on prittewella.

In the vocabulary list above, all the nouns are grouped together, and

their plurals given. I’ve also noted whether they’re strong, weak, or

in the ‘others’ group. Some words, like wheat, barley or food, aren’t

usually used in the plural, while others, like oats, don’t work well as

singulars! ‘spell’ as a singular noun, means a piece of news. From

‘godspell’, or good news, comes the NE word ‘gospel’.

singan to sing

hélan

to heal

growan to grow

bringan to bring

healdan to hold / keep

genéosian to visit

hwilum sometimes

swa

such as

wid

against

There’s some more

vocabulary on the left to help

you with Leofwin’s text.

The first Viking raids on English shores took place at

the end of the 790’s. In the late 800’s, Alfred the

Great agreed to give control of half of England to the

Danes — ‘the Danelaw’. After some decades of peace

there have been renewed Viking raids in Leofwin’s

time, and thane Godweard has to organise regular

watches on the estuary for raiders.

Danes and Norwegians came to be known as Vikings

RAARGH! You’ll be hearing more from

us Vikings later in the book!

45

leornungdel 3

7. Here are the new verbs used in Leofwin’s description: can you fill in the gaps in the last

three? (clue: ‘genéosian’ works like ‘oneardian’ in section 2 above)

TO BRING

TO HOLD

TO VISIT

ou bringest

Ou healdest

OU.

wé, gé, hie bringad

we, gé, hie ...

We, ce; hie:.,

Just as hé, héo and hit always work in the same way,

so wé, gé and hie always work the same way too.

In the verb boxes above, therefore, wé, gé and hie are grouped together. From now on, verb

boxes will be presented this way — it’s easier, and gives you all the information you need.

Lots more about how verbs work in unit 4.

46

ee,

(ee,

*

Oe_La7

t

‘

x

wy

‘PY

Ozxt scéap

0a scéap

Oet swin

6a swin

Si.GMs

ae

se wyrm

6a wyrmas

(se snaca/ 64 snacan)

tute outside

8. déor and néat

dzet hors / 64 hors

se Goh /64 Eos

se coce 64 coccas

séo hén 6a hennan

dzet cicen 64 cicenu

se hara

6a haran

se bera

0a beran

47

wild animals and domesticated animals

seo atorcoppe

0a Atorcoppan

séo lobbe / 6a lobban

9. Say what kind of noun these are:

Example — hund = strong masculine

1. hors

2. hen

3. gat

4. hara

5. atorcoppe

leornungdel! 3

You could work out what all the others are, too. Answers at the back! ‘déor’ and néat’ are

both strong neuter nouns, so their plurals don’t change. Here are some more animals (you’ll

find this table useful for doing the task in section 11):

brocc / broccas (strong m)

heort / heortas (strong m)

eofor / eoferas (irregular m)

leax / leaxas (strong m)

hron / hronas (strong m)

fox / foxas (strong m)

frogga / froggan (weak m)

dora / doran (weak m)

draca / dracan (weak m)

acweorna / Acweornas (weak m)

fléoge / fléogan (weak f)

buterfléoge / buterfléogan (weak f)

10. Look at these sentences:

brada singed done song

se préost genéosad done tiin

hé heled 6a cwén

hé bringed det spell

wé growad done fodan

godweard heef6 64 sulh

hé healded dzt land

_ badger

ic eom draca! ic

oneardie done béorg

stag ~

boar

salmon

whale

fox

frog

bee

dragon

squirrel

In the first sentence left, the song is being sung. In the

second, the town is being visited, while in the third,

the woman is being healed. The news is being

brought, and the food is being grown. The land is

being held, and the plough is being had, although it

may sound a little strange.

In grammar, the song is the ‘object’ of the verb ‘sing’.

Brada, who’s doing the singing, is the ‘subject’. In the

second sentence, the priest is the subject, and the town

is the object. What are the subjects and objects in the

other sentences?

48

ute outside

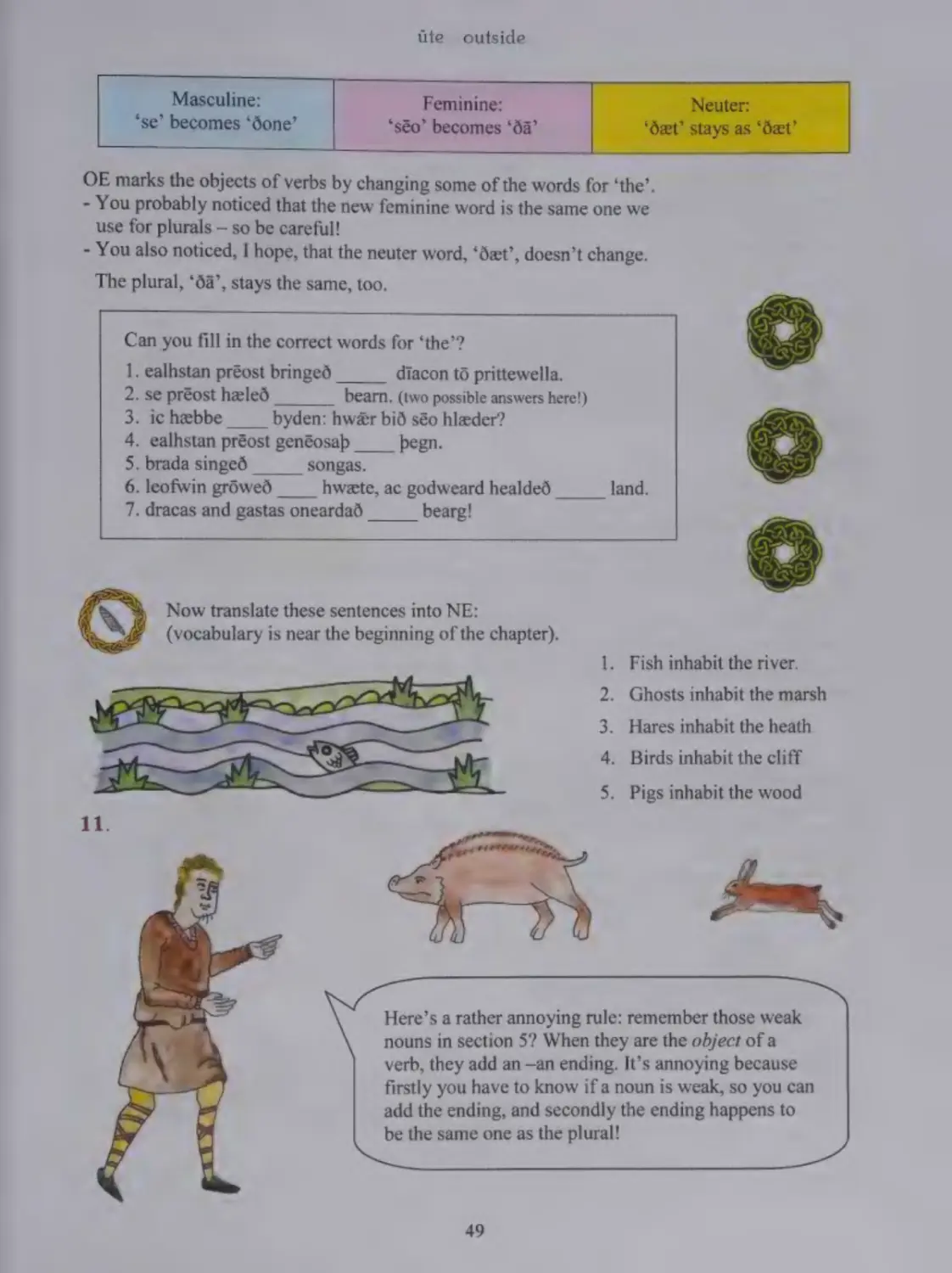

Masculine:

_ Feminine:

‘se’ becomes ‘done’

*séo’ becomes ‘6a’

OE marks the objects of verbs by changing some of the words for ‘the’.

- You probably noticed that the new feminine word is the same one we

use for plurals — so be careful!

- You also noticed, I hope, that the neuter word, ‘det’, doesn’t change.

The plural, ‘6a’, stays the same, too.

Can you fill in the correct words for ‘the’?

1. ealhstan préost bringed

diacon to prittewella.

2. se préost heeled

bearn. (two possible answers here!)

3. ic heebbe byden: hwér bid séo hlader?

4. ealhstan préost genéosab _ begn.

5. brada singed

songas.

6. leofwin growed __—__—shweete, ac godweard healded

land.

7. dracas and gastas oneardad

bearg!

Now translate these sentences into NE:

(vocabulary is near the beginning of the chapter).

1. Fish inhabit the river.

2. Ghosts inhabit the marsh

3. Hares inhabit the heath.

4. Birds inhabit the cliff

oF Pigs inhabit the wood

Here’s a rather annoying rule: remember those weak

nouns in section 5? When they are the object of a

verb, they add an —an ending. It’s annoying because

firstly you have to know if a noun is weak, so you can

add the ending, and secondly the ending happens to

be the same one as the plural!

49

leornungdel 3

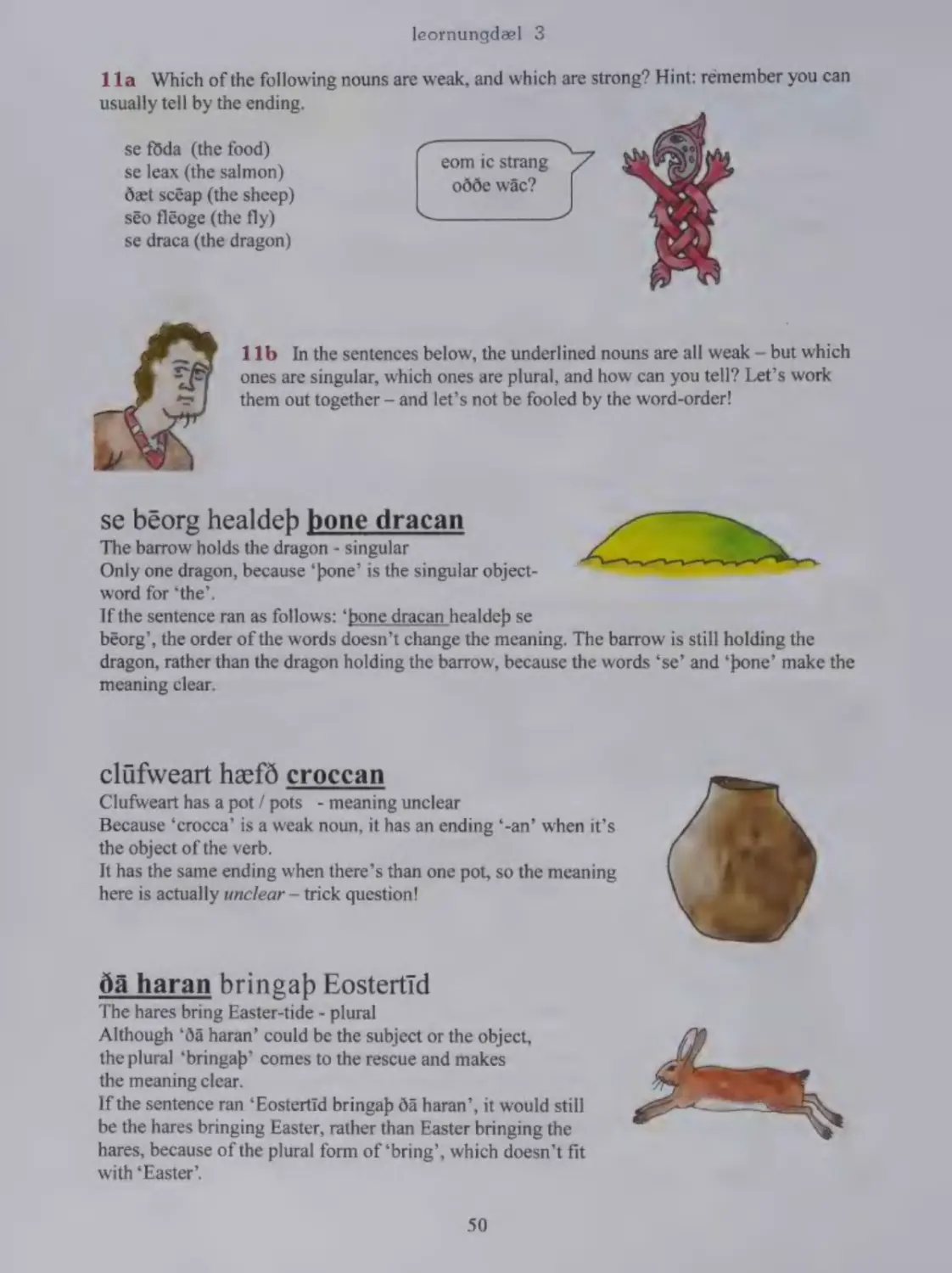

11a Which of the following nouns are weak, and which are strong? Hint: remember you can

usually tell by the ending.

se foda (the food)

se leax (the salmon)

Ozet scéap (the sheep)

séo fléoge (the fly)

se draca (the dragon)

eom ic strang

0d6d0e wac?

11b_ In the sentences below, the underlined nouns are all weak — but which

ones are singular, which ones are plural, and how can you tell? Let’s work

them out together — and let’s not be fooled by the word-order!

se béorg healdeb bone dracan

The barrow holds the dragon - singular

Only one dragon, because ‘pone’ is the singular object-

word for ‘the’.

If the sentence ran as follows: ‘bone dracan healdep se

béorg’, the order of the words doesn’t change the meaning. The barrow is still holding the

dragon, rather than the dragon holding the barrow, because the words ‘se’ and ‘pone’ make the

meaning clear.

clufweart hefd croccan

Clufweart has a pot / pots - meaning unclear

Because ‘crocca’ is a weak noun, it has an ending ‘-an’ when it’s

the object of the verb.

It has the same ending when there’s than one pot, so the meaning

here is actually unclear — trick question!

64 haran bringab Eostertid

The hares bring Easter-tide - plural

Although ‘6a haran’ could be the subject or the object,

the plural ‘bringab’ comes to the rescue and makes

the meaning clear.

If the sentence ran ‘Eostertid bringap 6a haran’, it would still

be the hares bringing Easter, rather than Easter bringing the

hares, because of the plural form of ‘bring’, which doesn’t fit

with ‘Easter’.

50

ute outside

preost and diacon hef6 séo cirice

The church has a priest and a deacon. — singular

The word ‘séo’ tells you straight away that we’re talking

about just one thing. ‘cirice’ with its ‘e’ ending makes that

even clearer.

The word-order may have thrown you here, but if the

meaning was that the the priest and deacon have the church,

then it would have read ‘préost and diacon habbad 44 cirican’.

Ealhstan genéosa6 64 cirican

Ealhstan visits the church / the churches — meaning unclear

Again, because church is a weak noun in OE, the ending ‘-an’ could be

there because it’s the object, or because it’s plural. ‘6a’ doesn’t help, for

the same reasons.

12. A note about that word-order. In NE, the order of the words is very

important in making the meaning of a sentence clear. ‘man bites dog’ /

‘dog bites man’ is an obvious example. We can change the word-order

around, but it’s unusual, and the effect is often quite dramatic —

-Many times she wrote him a letter, but never a word did she have in return...

-A cold night they had, but came the morning, and the weather improved...

OE can play around with word order much more than NE, because the endings usually make it

clear what job each word is doing the sentence. In fact it’s something of a characteristic of OE,

as we will see later on.

13. Basic survival: revision and survival guide!

Match up the numbers and letters!

1) ic poncie dé

a) yes

2) na

b) no

3) géa

c) please

4) ic sarie

d) thank you

5) éala

e) hello

6) ic bidde dé

f) goodbye

7) fera pi wel

g) sorry

It’s time to gather up the basic phrases you already know, and add

some new ones, so that you could survive the first day if you time-

travelled to visit me and my family in Prittewella. First, match up

the NE and OE words and phrases above. Then listen to and read the

phrases, on the next two pages. Repeating them and copying them

down will help you to remember.

a

leornungdel 3

godne daeg

good day

godne mergen

wes Ou hal / westu hal

:

good morning

wesao gé hale

:

be well

be well (plural)

god 2fen

good evening

ic gréte 0é

ic gréte ow ealle

;

j

god niht

I greet you

py

good night

I greet you all i

f

a

welcumen

welcome

hii g#6 hit?

hit g#0 wel

how goes it?

it goes well

gled 0é t6 métenne

glad to meet you

fer bi wel

ferad gé wel

farewell

(singular and

plural)

God 0é mid sie

God be with you

(goodbye)

géa, giese

yes

.aee

r

Ieee,

ic bidde 6é

ic sarie

please

i,

I’m sorry

forgief mé

ic doncie 6é

:

:

forgive me

thank you

:

ute outside

hweet is dis ?

what’s this?

hii hated dis?

What’s this called?

hii eald eart pi?

How old are you?

ic eom eahta géar eald

ic eom eahta wintra

Im eight years old

ic wolde...

I’d like...

wilt Ou...

do you want to...

hi hatest du?

What’s your name?

min nama is brada

ic hate brada

my name is Brada

I’m called Brada

hweer is... ? is/sind

where is...? there is/are

ic lufie... / ... licad mé

I love ... / I like...

saga det eft

say that again

ic nat

I don’t know

min gebyrdtid bip...

my birthday is...

hwr eardast 0u?

Where do you live?

ic eardie on prittewella

I live in Prittlewell

ic eom godweardes scop

I’m Godweard’s singer

.. ne licad mé / ic hatie..

I don’t like... / I hate..

ic lyste bet...

I prefer...

leornungdel 3

Now answer the questions:

1 What are the two OE words for ‘yes’? 2 Which two people say they’re sorry?

3 How do you say ‘good night’?

4 What does Godweard ask his daughter?

5 Why does Elfgifu use two greetings?

6 What does ‘ic nat’ mean?

7 What does Fat Freda ask you?

8 Which new character is playing the lyre?

9 Which sentence means ‘I am 8 winters’? 10 What does Agata ask?

14. Prittlewell in Anglo-Saxon times

Prittlewell village still exists, but it’s now part of the much larger sea-side town of Southend-on-

Sea. Before the coming of the railway in the 1860’s, Southend was hardly more than a collection

of fishermen’s cottages on the sea-shore, while Prittlewell is listed in the Domesday Book of

1086. There’s no trace of any Anglo-Saxon buildings, but a filled-in stone doorway at St. Mary’s

church dating to the mid-seventh century suggests not just a community living here fourteen

hundred years ago, but a community important enough to have a stone church. The doorway also

contains re-used Roman tiles, which pushes the life of the village even further back in time.

In the 1920’s and 30’s, pre-Christian Anglo-Saxon burials were discovered at Root’s Hall in

the heart of Prittlewell, and at the edge of nearby Priory Park, again strongly suggesting a

permanent village settlement from the earliest Anglo-Saxon times.

In 2003, the discovery of a rich chambered tomb at the Priory Park site made Prittlewell famous

in the archaeological world. The man in the grave lived at the beginning of the 600’s, had both