Similar

Text

THE CAMBRIDGE

HISTORY OF

CHINA

VOLUME 3

SUI AND T’ANG CHINA

589-906

PARTI

THE CAMBRIDGE HISTORY

OF CHINA

General editors

Denis Twitchett and John K. Fairbank

Volume 3

Sui and T’ang China, 589-906, Part 1

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE CAMBRIDGE

HISTORY OF

CHINA

Volume 3

Sui and T’ang China, 589-906, Part I

edited by

DENIS TWITCHETT

CAMBRIDGE

UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao Paulo, Delhi

Cambridge University Press

32 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10013-2473, USA

www.cambridge.org

Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/978052I214469

© Cambridge University Press 1979

This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception

and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements,

no reproduction of any part may take place without

the written permission of Cambridge University Press.

First published 1979

Reprinted 1993, 1997. 2006. 2007

Printed in the United States of America

A catalog record for this publication is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9 hardback

Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for

the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or

third-party Internet Web sites referred to in this publication

and does not guarantee that any content on such

Web sites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

GENERAL EDITORS’ PREFACE

In the English-speaking world, the Cambridge Histories have since the

beginning of the century set the pattern for multi-volume works of

history, with chapters written by experts on a particular topic, and unified

by the guiding hand of volume editors of senior standing. The Cambridge

modem history, planned by Lord Acton, appeared in sixteen volumes

between 1902 and 1912. It was followed by The Cambridge ancient history,

The Cambridge medieval history, The Cambridge history 0/ English literature,

and Cambridge Histories of India, of Poland, and of the British Empire.

The original Modem history has now been replaced by The new Cambridge

modem history in twelve volumes, and The Cambridge economic history of

Europe is now being completed. Other Cambridge Histories recently

undertaken include a history of Islam, of Arabic literature, of the Bible

treated as a central document of and influence on Western civilization,

and of Iran and China.

In the case of China, Western historians face a special problem. The

history of Chinese civilization is more extensive and complex than that

of any single Western nation, and only slightly less ramified than the

history of European civilization as a whole. The Chinese historical record

is immensely detailed and extensive, and Chinese historical scholarship

has been highly developed and sophisticated for many centuries. Yet

until recent decades the study of China in the West, despite the important

pioneer work of European sinologists, had hardly progressed beyond the

translation of some few classical historical texts, and the outline history

of the major dynasties and their institutions.

Recently Western scholars have drawn more fully upon the rich

traditions of historical scholarship in China and also in Japan, and greatly

advanced both our detailed knowledge of past events and institutions,

and also our critical understanding of traditional historiography. In

addition, the present generation of Western historians of China can also

draw upon the new outlooks and techniques of modem Western historical

scholarship, and upon recent developments in the social sciences, while

continuing to build upon the solid foundations of rapidly progressing

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

vi GENERAL EDITORS* PREFACE

European, Japanese and Chinese sinological studies. Recent historical

events, too, have given prominence to new problems, while throwing

into question many older conceptions. Under these multiple impacts the

Western revolution in Chinese studies is steadily gathering momentum.

When The Cambridge history of China was first planned in 1966, the

aim was to provide a substantial account of the history of China as a

bench mark for the Western history-reading public: an account of the

current state of knowledge in six volumes. Since then the out-pouring of

current research, the application of new methods, and the extension of

scholarship into new fields, have further stimulated Chinese historical

studies. This growth is indicated by the fact that the History has now

become a planned fourteen volumes, which exclude the earliest pre¬

dynastic period, and must still leave aside such topics as the history of

art and of literature, many aspects of economics and technology, and

all the riches of local history.

The striking advances in our knowledge of China’s past over the last

decade will continue and accelerate. Western historians of this great and

complex subject are justified in their efforts by the needs of their own

peoples for greater and deeper understanding of China. Chinese history

belongs to the world, not only as a right and necessity, but also as a

subject of compelling interest.

JOHN K. FAIRBANK

DENIS TWITCHETT

June 1976

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CONTENTS

General editors' preface page v

.List of maps and tables x

Preface to volume } xii

List of abbreviations xiv

1 Introduction i

by Denis Twitchett, Professor of Chinese, University of Cambridge

The establishment of national unity 2

Institutional change 8

Economic and social change 22

Sui and T’ang China and the wider world 32

The problem of sources 38

2 The Sui dynasty (581-617) 48

by the late Arthur F. Wright, formerly Charles Stymour

Professor of History, Yak University

Sixth-century China 49

Wen-ti (reign 581-604): the founder and his advisers 57

Major problems of the Sui 73

Yang-ti (reign 604-17): personality and life style 115

Problems of Yang-ti’s reign 128

3 The founding of the T’ang dynasty: Kao-tsu

(reign 618-26) 150

by Howard J. Wechsler, Associate Professor of History and

Asian Studies, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

The seizure of power 15 3

Extension of dynastic control throughout China 160

Internal policies 168

Relations with the Eastern Turks 181

The Hsiian-wu Gate incident and the transfer of power 182

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CONTENTS

viii

4 T’ai-tsung (reign 626-49) the consolidator 188

by Howard J. Wechsler

T’ai-tsung’s ministers 193

‘Regional politics’at the court 200

Domestic policies and reforms 203

Policies designed to strengthen central authority 210

Foreign relations 219

The struggle over the succession 236

5 Kao-tsung (reign 649-83) and the empress Wu: the

inheritor and the usurper 242

by Denis Twitchett and Howard J. Wechsler

Rise of the empress Wu 244

The empress Wu in power 251

Kao-tsung’s internal policies 273

Foreign relations 279

6 The reigns of the empress Wu, Chung-tsung and Jui-

tsung (684-712) 290

by Richard W. L. Guisso, Assistant Professor of History,

University of Waterloo, Ontario

The period of preparation (684-90) 290

The Chou dynasty (690-705) 306

Chung-tsung and Jui-tsung (reigns 705-12) 321

The period in retrospect 329

7 Hsiian-tsung (reign 712-56) 333

by Denis Twitchett

The early reign (713-20): Yao Ch’ung and Sung Ching 345

The middle reign (720-36) 374

Li Lin-fu’s regime (736-52) 409

Yang Kuo-chung’s regime (752-6) 447

The end of the reign 453

8 Court and province in mid- and late T’ang 464

by C. A. Peterson, Professor of History, Cornell University

The north-eastern frontier 468

Te-tsung (reign 779-805) 497

The provinces at the beginning of the ninth century 514

Hsien-tsung (reign 805-20) and the provinces 522

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CONTENTS ix

The provinces under Hsien-tsung’s successors 538

Decline of the provincial system j 52

9 Court politics in late T’ang times 561

by Michael T. Dalbv, Assistant Professor of Chinese History,

University of Chicago

The rebellion of An Lu-shan and its aftermath (75 5—86) 561

Development of the inner court (786-805) 586

Centralization under Hsien-tsung (805-20) 611

Mid-ninth-century court (820-59) 635

10 The end of the T’ang 682

by Robert M. Somers, Assistant Professor of History,

University of Missouri-Columbia

Fiscal problems, rural unrest and popular rebellion 682

The court under I-tsung (reign 859-73) 700

Hsi-tsung (reign 873-88) 714

New structure of power in late T’ang China 762

Glossary - index 790

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

MAPS AND TABLES

Maps

1 Sui China, 609

2 Sui and T’ang canal system

3 Late Sui rebellions, 613-16

4 Late Sui rebellions, 617

5 T’ang conquest

6 T’ang China, 639

7 T’ai-tsung’s advance into central Asia

8 Kao-tsung’s protectorates in central Asia

9 Kao-tsung’s interventions in Korea

10 Military establishment under Hsiian-tsung

11 T’ang China, 742

12 An Lu-shan’s rebellion

13 T’ang provinces, 763

14 Ho-pei'rebellions, 781-6

15 T’ang provinces, 785

16 Fiscal divisions of the empire, 810

17 T’ang provinces, 822

18 Banditry in the 830s and 840s

19 Ch’iu Fu and P’ang Hsiin rebellions

20 Wang Hsien-chih’s bandit confederation, 874-8

21 Huang Ch’ao’s movements, 878-80

22 Distribution of power after Huang Ch’ao’s rebellion, 885

page

129

136

145

147

164

204

227

281

283

368.

403

454

488

502

508

520

539

686

698

728

738

7б5

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

MAPS AND TABLES xi

Tables page

1 Sui emperors and their reign periods xvi

2 Outline genealogy of the T’ang imperial family xvii

3 T’ang emperors and their reign periods xviii

4 Marriage connections of the T’ang royal house xx

5 T’ang weights and measures xx

6 Land distribution under the Sui dynasty 94

7 Location of Hsuan-tsung’s court 3 5 8

8 Frontier commands under Hsiian-tsung 367

9 High leadership of ninth-century political factions 643

10 Summary of-data on identifiable members of mid-ninth-century

political factions 633

11 Distribution of power after Huang Ch’ao’s rebellion 764

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PREFACE TO VOLUME 3

The Chinese is transliterated according to the Wade-Giles system, which

for all its imperfections is employed almost universally in the serious

literature on China written in English. For Japanese, the Hepburn system

of romanization is followed.

Chinese personal names follow their native form, that is with the

surname preceding the given name.

Place names present a complex problem, as many of them underwent

changes during the course of the period covered by this volume, some

of them several times. In general we have used the names in use in the

period until 741 and employed as the head-entries in the monographs

on geography in the two Dynastic Histories of the T’ang, even when

(as for example from 742 to 758) this is strictly speaking an anachronism.

In some cases there is possible confusion between modem provincial

names, used as a regional description, and the names of T’ang provinces.

The convention is adopted of hyphenating the syllables of T’ang place

names, and not hyphenating modem names. For example Hopei represents

the modem province, Ho-pei the T’ang province. For modem place

names some non-standard spellings which have become customary, for

example Nanking for Nanching, Sian for Hsian, are retained.

For dates the Chinese and Western years do not exactly coincide. The

Western year which nearly coincides with the Chinese year is used as

the equivalent of the Chinese year. For example 716 is used as equivalent

to the fourth year K’at-yiian, which in fact ran from 29 January 716 until

1 5 February 7x7 (it included an intercalary month). Dates, where given,

are expressed in Chinese lunar months and days, since this makes reference

to the Chinese sources simpler than if they were expressed in the Western

calendar. Western equivalents may easily be found for the T’ang period

in Hiraoka Takeo, Todai no kqyomi (Kyoto, 1954!.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PREFACE TO VOLUME } хШ

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank the American Council of Learned Societies for two

grants which have enabled us to support the editorial assistance of Robert

Somers and Stephen Jones in the preparation of this volume. Mr Somers

undertook preliminary editing on chapters i to 5. Mr Jones, in co¬

operation with Cambridge University Press, has edited the text of the

entire volume. The maps were prepared by the editor and drawn by

Ken Jordan FRGS and Reg Piggott.

We would also like to acknowledge the generous support given by

the American Council of Learned Societies to the Conference on T’ang

Studies held at Cambridge in 1969. That conference, in which all but

one of the contributors to this volume took part, gave a new impetus

to the study of the period, and proved invaluable in formulating the

basic outline of Sui and T’ang history, and in establishing the major

problems to which this volume and its successor attempt to provide

answers.

My co-chairman at that conference, and the co-editor of the symposium

volume, Perspectives on the T’ang, in which the papers were published,

was the late Arthur F. Wright, who died while this volume was being

prepared for press. I and my fellow contributors, several of whom have

been his pupils, and all of whom were his personal friends, would wish

to record our tribute to the great contribution he made to the study of

medieval Chinese history, and our sadness that he did not live to see the

completion and publication of this volume, in the progress of which he

had been so deeply involved.

DCT

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ABBREVIATIONS

AM

BEFEO

BSOAS

CTS

CTW

CYYY

HJAS

HTS

JA

JAOS

JAS

LSYC

MSOS

SGZS

SPPY

SPTK

SS

TCTC

TD

TFYK

THGH

THY

TLT

TP

TSCC

TT

TTCLC

TYGH

тггк

WYYH

Asia Major (new series)

Bulletin de I’Ecole Franfaise d’Extreme-Orient

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies

Chiu T’ang shu

Ch’Uan T’ang-wen

Kuo-li chung-yang yen-chiu-yiian Li-shih yu-yen yen-chiu-so chi-k’an

(Academia Sinica)

Harvard journal of Asiatic Studies

Hsin T’ang shu

Journal Asiatique

Journal of the American Oriental Society

Journal of Asian Studies

Li-shihyen-chiu

Mitteilungen des Seminars fiir Orientalische Sprachen %u Berlin

Shigaku % asshi

Ssu-pu pei-yao edn

Ssu-pu ts’ung-k’an edn

Sui shu

T^u-chih t’ung-chien

Taisho shinshii Dai^okyo edn of the Buddhist Tripitaka

Ts’e-fuyiian-kuei

Toho gakuho; refers to the journal of this name published in

Kyoto unless specified THGH (Tokyo).

T’ang hui-yao

T’ang liu-tien

T’oung pao

Ts’ung-shu chi-ch’eng edn

T’ung tien

T’ang ta chao-ling chi

Toy6 gakuho

Wen-hsien t’ung-k’ao

Wen-yuan у ing-hua

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ABBREVIATIONS

XV

EDITIONS EMPLOYED FOR MAIN PRIMARY SOURCES

The Standard Dynastic Histories are cited in the punctuated critical texts

published by the Chung-hua shu-chii, Peking. This edition is also available

in a reprint published in Taipei. Works from this series to which reference

is made are:

Ch’enshu, z vols., 1972

Chiu T’angshu (abbreviated as CTS), 16 vols., 1975

Choushu, 3 vols., 1971

Hsin T’angshu (abbreviated as HTS), 20 vols., 1975

Hsin Wu tai shih, 3 vols., 1974

Nan shih, 6 vols., 1975

Pei Ch’i shu, 2 vols., 1972

Pei shih, 10 vols., 1974

Sui shu (abbreviated as SS), 6 vols., 1973

Wei shu, 8 vols., 1974

Collected works of individual authors, unless otherwise specified, are

cited from the editions reprinted in the Ssu-pu ts’ung-k’an.

Buddhist works, unless otherwise specified, are cited from the Taisho

shinshu Dai^okyo edition of the Buddhist canon.

The editions of other frequently cited primary sources are as follows:

Ch’uan T’ang-wen, imperial edn, 1814; reprinted in facsimile, Hua-wen

shu-chii, Taipei, 1961; Hua-wen shu-chii, Taipei, 1961. (Abbreviated

as CTW)

T^u-chih t’ung-chien, Ku-chi ch’u-pan-she edn, Peking, 1956. (Abbreviated

as TCTQ

Ts’e-fuyiian-kuei, edn of Li Ssu-ching, 1642; reprinted in facsimile Chung-

hua shu-chii, Peking, i960; Ching-hua shu-chii, Taipei, 1965. (Abbre¬

viated as TFYK)

T’ang bui-yao, Kuo-hsiieh chi-pen tsiing-shu edn, Shanghai, 1935; reprinted

Chung-hua shu-chii, Peking, 1957. (Abbreviated as THY)

T’ang liu-tien, edn of Konoe Iehiro, 1724; reprinted in facsimile Wen-hai

ch’u-pan-she, Taipei, 1962. (Abbreviated as TLT)

T’ung tien, Shih T’ung edn, Shanghai, 1936. (Abbreviated as TT)

T’ang ta chao-ling chi, Shang-wu yin-shu-kuan edn, Shanghai, 1959.

(Abbreviated as TTCLC)

Wtn-hsien t’ung-k’ao, Shih-t’ung edn, Shanghai, 1936. (Abbreviated as

WHTK)

Wen-yuan ying-hua, edn of 1567 with prefaces by T’u Tse-min and Hu

Wei-hsin; reprinted in facsimile, Chung-hua shu-chii, Peking, 1966.

(Abbreviated as WYYH)

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Xvi TABLES

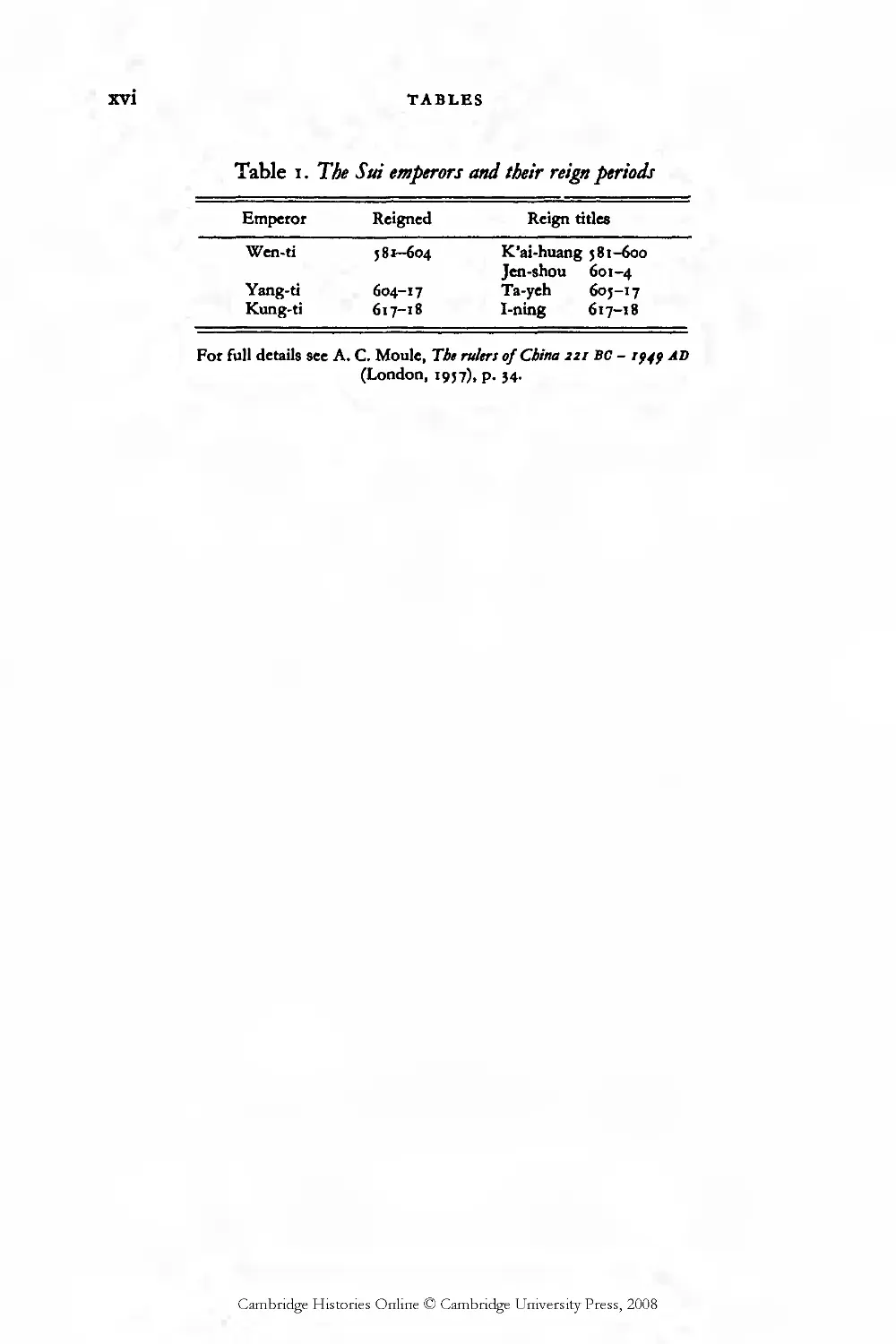

Table i. The Sui emperors and their reign periods

Emperor

Reigned

Reign titles

Wen-ti

381-604

K’ai-huang 581-600

Jen-shou 601-4

Yang-ti

604-17

Ta-yeh

605-17

Kung-ti

617-18

I-ning

617-18

For full details see A. C. Moule, The rulers of China 221 BC - 1949 AD

(London, 1957), p. 34.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

TABLES

XVU

Table z. Outline genealogy of the T'ang imperial family

Kao-tcu j66-6j5

reigned 618-26

1 1 1 1 1 1 И 1 1 I 1 1 1 1 I I I I

LJ Chieo-cb’eng

HA 619-26

Tai-tsung $99-649

reigned 626-49

>«i

Li Ch’eng-ch’ien

HA 673-47

1 Г

1 1 Г-Д~"1—1 г

1—I

Kao-tsung 628-8)

НЛ 64), reigned 649-8)

>1 1 1

Li Chung

HA 6)2-6

I jib I

Li Hung

HA 6)6-75

6thl

Li Hsien

HA 67J-80

7«h|

IZ

Empress Wu Tse-t’ien

7 reigned 690-70)

3rd i

li Ch'ung-chQn

HA 706-7

4th

8th|

Chung-tsung 656-710

HA 68o, reigned 684

r

jui-tsung 662-716

reigned 684-90

under empress Wu

Imperial heir 698

restored 705-10

restored 710-12

Li Ch’ung-mao

reigned as Wen-wang

under empress Wei 710

I

HsQan-tsung 685-762

HA 710, reigned 7is-)6

I I I I II I I I I I II I I li

)0 I sons

T

ПТТТП

and|

Li King

HA 713-37

и I

Su-tsung 711-62

HA 738, reigned 756-62

1 1 1 r

14 I «one

T г

Tai-tsung 717-79

HA 7j8„ reigned 761-79

1—I—Г

"I—I—I—I—I—I—I—I—I—I—I

Tc-tsung 741-807

HA 764, reigned 779-80]

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

Shun-taung 761-806

НЛ 779, reigned 8oj

T—I—I—I—I—I—Г

i—I—I—I—I—Г

Hticn-tsung 778-810

HA 807, reigned 807-10

"I—Г

~l—I—I

ж Г

LlNin;

3rd

Ning

HA 809-11

1 I 1 I I I I I li)tbl II I I I I I

Mu-tsung 795-824

HA 812, reigned 820-4

Hsiuan-tsung 810-59

reigned 846-59

,„l

2nd | 1 1

5lh|

Ching-tsung 809-27

Wen-tsung 809-40

Wu-tsung 8(4-46

HA 822, reigned 824-7

reigned 827-40

reigned 840-6

1—1—г

1 !'h|

Lt Ch’cng-mcl

HA 839-40

n—1—1

Li Yung

HA 832-6

i—i—1—1—1—1—г

I-tsung 833-77

reigned 839-73

Ж

Hsi-tsung 862-88

reigned 873-88

7'Ь I

Chao>tsung 867-904

reigned 888-904

10 I sons

„,1 I 'll I I l9th|

Li Yil Ai-ti 892-908

HA 897-904 reigned 904-7

HA: heir apparent

This chart shows the

line of succession;

also those heirs apparent

who did not succeed to

the throne.

Other royal princes

were given the tith of

heir apparent as a

posthumous honour, but

did not actually serve

as heir apparent.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

TABLES

xviii

Table 5. The T’ang emperors and their reign periods

Emperor

Reigned

Reign titles

Kao-tsu

618-26*

Wu-te

618-26

T’ai-tsung

626-49

Chen-kuan

627-49

Kao-tsung

649-83

Yung-hui

650-5

Hsien-ch’ing

6j6—6O

Lung-shuo

661-3

Lin-te

664-5

Ch’ien-feng

666-7

Tsung-chang

668—9

Hsien-heng

670-3

Shang-yiian

674-3

I-feng

676-9

T’iao-lu

679

Yung-lung

680-1

K’ai-yao

681-2

Yung-ch’un

682-5

Hung-tao

683

Chung-tsung

684+

Ssu-shcng

684

(court under control

of empress Wu)

Jui-tsung

684-90!

Wen-ming

684

(court under control

Kuang-chai

684

of empress Wu)

Ch’ui-kung

685-8

Yung-ch’ang

689

Tsai-ch’u

689-90

Empress Wu Tse-t’ien

690-705

T’ien-shou

690-2

Chou ‘dynasty’

Ju-i

692

Ch’ang-shou

692-4

Yen-tsai

694

Cheng-sheng

694-5

T’ien-ts’e wan-sui 695

Wan-sui teng-

696

feng

Wan-sui t’ung-

696-7

t’ien

Shen-kung

697

Sheng-li

697-700

Chiu-shih

700-Х

Ta-tsu

701

Ch’ang-an

701-4

Chung-tsung restored

705-10

Shen-Iung

705-7

Ching-lung

707-10

Shao-ti

7I0t

T’ang-lung

710

(court under control

of empress Wei)

Jui-tsung restored

710-12*

Ching-yiin

710-iz

T’ai-chi

712

Yen-ho

71*

Hsuan-tsung

7x2-56*

Hsien-t’ien

712-13

K’ai-yfian

7»3-4*

Tien-pao

742-56

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

TABLES

xix

Table 3 (coni.).

Emperor

Reigned

Reign titles

Su-tsung

756-62

Chih-te

756-8

Ch’ien-yiian

758-60

Shang-yiian

760-1

Yiian

761-2

Tai-tsung

762-79

Pao-ying

762-5

Kuang-te

765-4

Yung-t’ai

765-6

Ta-li

766-79

Te-tsung

779-805

Ta-li

779

Chien-chung

780-5

Hsing-yiian

785-4

Chen-yiian

785-805

Shun-tsung

00

0

Wl

*

Chen-yuan

805

Yung-chen

805

Hsien-tsung

805-20

Yung-chen

805

Yiian-ho

806-20

Mu-tsung

820-4

Ch’ang-ch’ing

821-4

Ching-tsung

824-7

Pao-li

825-7

Wen-tsung

827-40

T’ai-ho

827-56

K’ai-ch’eng

856-40

Wu-tsung

840-6

Hui-ch’ang

841-6

Hsiuan-tsungi

846-59

Ta-chung

847-59

I-tsung

859-75

Heien-t’ung

860-75

Hsi-tsung

875-88

Ch’ien-fu

874-80

Kuang-ming

880-1

Chung-ho

881-5

Kuang-ch’i

885-8

Wen-te

888

Chao-tsung

888-904

Wcn-tc

888

Lung-chi

889

Ta-shun

890-2

Ching-fu

892-5

Ch’ien-ning

894-8

Kuang-hua

898-901

T’ien-fu

901-4

T’ien-yu

9°4

Ai-ti

904-7

T’ien-yu

904-7

* abdicated % correctly transliterated Hsiian-tsung. We have used this irregular form

to avoid confusion with Hsiian-tsung (reign 712-56)

f deposed

For full details see A. C. Moule, The rulers of Cbitut 221BO -1949 AD (London, 1957),

pp. 54-62. For detailed calendar see Hiraoka Takeo, Todai no kqyomi (Kyoto, 1954).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

XX

TABLES

Table 4. Marriage connections of the T'ang royal house

Yang Chung

Li Hu

Tu-ku Hsin Yii-wen T’ai

Yang Chien => 7th d. Li Ping = 4th d.

(SuiWen-ti) 1

1

1

1

Li Yiian

i

i

(T’ang Kao-tsu)

i

Yang Kuang

(Sui Yang-ti)

' 1

ist d. >=

I I

Yii-wen Yung Yii-wen Yil

(N. Chou Wu-ti) (N. Chou Ming-ti)

Yii-wen YOn

(N. Chou Hsiian-ti)

1st d.

Yii-wen Yen

(N. Chou Ching-ti)

Tu-ku dan = Li dan (T’ang royal house)

Yang dan (Sui royal house) Yu-wen dan (Northern Chou royal house)

Yang Chung, Li Hu and Yii-wen T’ai, the founders of the Sui, T’ang and Northern Chou

royal houses, all served as high-ranking generals during the Western Wei, together with

Tu-ku Hsin, to whose daughters all three married their sons.

Table 5. T'ang weights and measures

(a) Length

io ttun = i cb'ib (slightly less than i English foot)

5 cb'ib = i pu (double pace)

io cb’ib «= i cbang

1800 cb'ib = i // (approx. | English mile)

(b) Area

i той = a strip i pu wide by 240 pu long (approx. 0-14 acre)

100 той =• i ch’ing (approx. 14 acres)

(<•) Capacity

3 tbeng = 1 ta-shtng (the standard pint)

10 ta-sbeng = 1 tou

10 tou — 1 bu

1 bu == 1 sbib (approx. 1} bushels)

(4) Weight

3 Hang = 1 ta-liang (the standard ounce)

16 ta-liang = 1 cbin (approx. 1} English lb)

(a) Cloth

1 p’i of silk = a length 1-8 cb'ib in width, 40 cb’ib long

i

tuan of hemp => a length i-8 cb’ib in width, 50 cb'ib long

Further details are given in S. Balazs, ‘BeitrSge zur Wittschaftsgeschichte der T’ang-Zeit’,

MSOS, 36 (1933) 49 ft

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

This volume is the first of two devoted to the Sui and T’ang dynasties

(581-907). It is designed to provide the reader with a narrative account of

this complex period, during which China underwent far-reaching changes

in political institutions, in her relations with the neighbouring countries,

in social organization, in the economy and in every sphere of intellectual,

religious and artistic life. The broader issues in institutions, social and

economic change and in intellectual developments are dealt with in

detail in Volume 4 which also contains a bibliography for both volumes.

A glance at this bibliography will show that a wealth of modern scholar¬

ship has been devoted to the T’ang. Chinese scholars have been attracted

to the period as one of the high points of Chinese political power and

influence, and as one of extraordinary achievements in every field of

culture and the arts. Japanese scholars have been drawn to the Sui

and T’ang not simply because of the intrinsic interest of the period, but

also because it was during these dynasties that Japan was most deeply

influenced by Chinese institutions. Consequently Japanese scholars have

had a deep and instinctive understanding of Sui and T’ang China which

provided so much of the fabric of their own state structure, laws and

institutions, art, literature and even of their written language. Western

scholars too have long been fascinated by the period — the first full scale

political history of the T’ang in a European language was completed by

Father Antoine Gaubil SJ in 1753* - and in recent decades have begun

to make their own distinctive contribution to the understanding of T’ang

China.

However, although the Sui and T’ang periods have been subjected to

more rigorous scrutiny by modern historians than any other period of

Chinese history prior to the nineteenth century, political history in the

1 Le P. Antoine Gaubil, SJ, Abrlgl de I’bistoire (binoise de la grande dynastic des T’ang in Mlmoires

eontemant les Cbinois, tome 15 (1791) pp. 399-516 and tome 16 (1814) pp. 1-365. In spite of

its dates of publication, this monumental work was completed in Peking in the mid¬

eighteenth century, and sent back to Paris by Gaubil in 1753. Tome 16 of the Mlmoires

eoneemant les Cbinois also includes articles by Gaubil on the Muslims under the T’ang

(pp. 373-5); on the T’ang population (pp. 375-8); on the Nestorian stele at Sian (pp. 378-83)

and on the countries of the western regions in T’ang times (pp. 383-95).

[ x 1

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

2

INTRODUCTION

broadest sense has been neglected and taken for granted. Surprisingly,

much of the ground covered in this volume has not previously been

examined in detail, even by modern Chinese historians. Only the Sui,

the first years of the T’ang, the reign of the empress Wu, the latter years

of Hsiian-tsung and the first decades of the ninth century have been

subjected to reasonably close analysis. For the rest, the best summary often

remains the amazingly lucid, critical and judicious account written by

Ssu-ma Kuang and his collaborators in the T^u-chih t'ung-chien completed

in 1085.2 As work on this volume has progressed, so our admiration for

this prince among historians has grown. The original aim of The Cambridge

history of China was to producie a summary of the current state of know¬

ledge, but in the event all the chapters in these volumes represent much

new research into previously neglected topics. Some of the results are

therefore tentative. But the placing of the results of many isolated studies

of specialized topics into the context provided by a detailed chronological

account has thrown into relief many unsuspected relationships between

developments in very different fields, and we feel confident that this

volume will provide the reader with a historical context which will add

new significance to the more specialized studies in volume 4.

By way of introduction I shall now outline some of the main themes

which run through the period and have attracted previous scholars’

attention, and also draw attention to the complex underlying problems

raised by the nature of our primary source material, which to a surprising

extent prescribes the limits of what the modern historian can accomplish.

The uneven coverage of the different periods in this volume reflects very

closely the uneven documentation at our disposal.

THE ESTABLISHMENT OF NATIONAL UNITY

The single most important long term development during these centuries

was the final re-establishment of Chinese national unity. In the preceding

period the unified empire set up by the Ch’in and the Han had been

shattered. The progressive breakdown of central authority in the latter

half of the second century was accompanied by the growth of many local

power structures. The Yellow Turbans and other popular rebellions of

the 180s and the decades of civil conflict and near anarchy which followed

them finally destroyed both the effective power and the authority of the

Han government. Military force became the sole source of authority, and

1 On Ssu-ma Kuang see Edwin G. Pulleyblank, ‘Chinese historical criticism: Liu Chih-chi

and Ssu-ma Kuang’, in W. G. Beasley and Edwin G. Pulleyblank, eds. Historians of China

and Japan (London, 1961), pp. 155-66. See also Edwin G. Pulleyblank, ‘The Tzyhjyh

Tongjiann Kaoyih and the sources for the period 730-763’, BSOAS, 13.2 (1950) 448-73.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ESTABLISHMENT OF NATIONAL UNITY

3

the emperor became a puppet controlled by the generals. The maintenance

of some degree of local stability and law and order lay in the hands of

powerful local magnates with personal control over extensive lands and

numerous client families of cultivators and military retainers. When the

last powerless Han emperor finally abdicated in favour of one of his great

generals in ad 220 China was split into three regional states, in none of

which did the central government have the unquestioned authority the

Han had enjoyed in its prime. Although the whole country was briefly

reunited under the Chin in 280, the new regime had little effective power

and soon fell victim to serious internal disorders. Almost immediately

afterwards, at the beginning of the fourth century, the north was overrun

by waves of non-Chinese nomadic peoples, and the Chin survived only as

a regional regime in the south. The invaders, the Tibetan Ch’iang and Ti

in the north-west, and the Hsiung-nu and various Turkish, proto-Mongol

and Tungusic peoples in the north, overran what had been the most

advanced, richest and most populous areas of China, establishing a

bewildering succession of petty shortlived dynasties. Northern China

suffered more than a century of constant warfare, anarchy, disruption and

physical devastation before the establishment of a stable unified northern

regime by the Toba Turks (the Northern Wei dynasty) in 440.

Although they attempted for decades to preserve their cultural identity,

the Toba, like their predecessors, found themselves forced to adopt

Chinese institutions and to collaborate with the Chinese elite. Their

traditionalist tribal aristocracy, feeling itself about to be absorbed by its

Chinese subjects, reacted violently and the ensuing tensions brought about

the division of the Northern Wei empire into two states, the Western Wei

(which became the Northern Chou in 557) in which the non-Chinese

elements remained strongest, and the Eastern Wei (which became the

Northern Ch’i in 550) in the north-east. Finally in 577 the Northern Chou

conquered the Northern Ch’i, reunifying northern China and reasserting

the political and military dominance of the north-west.

These centuries of political and social dominance by non-Chinese

peoples left deep marks on the society and institutions of northern China.

The nobility of the various foreign ruling houses constantly intermarried

with the Chinese elite. This was particularly the case in the north-west,

where two aristocractic groups emerged to form an elite very different

from the traditional Chinese ruling class. These groups, the Tai-pei

aristocracy of central and northern Shansi, and the far more powerful

Kuan-lung aristocracy with its power bases in south-west Shansi, Shensi

and Kansu, were not only of mixed blood. They had a life style strongly

influenced by nomadic customs; even well into the T’ang period many

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

4

INTRODUCTION

of them still spoke Turkish as well as Chinese; they were essentially a

military group rather than a civilian elite, living a hard, active outdoor

life; arid, as among the nomads, their womenfolk were far more indepen¬

dent and powerful than in traditional Chinese society.

In the north-eastern plain the great aristocratic clans of Shan-tung (the

area east of the T’ai-hang ranges, that is modern Hopei, Honan and

Shantung) had gone to great lengths to preserve their social and cultural

identity as the true heirs of the culture of the Han period. They scrupu¬

lously avoided intermarriage with the alien nobility, and had to an extent

remained aloof from court politics, remaining powerful in their regional

bases.

The Sui first came to power as the successor of the Northern Chou.

Like the ruling house of the Northern Chou, the family of its founder

Yang Chien (the future Wen-ti) was from the north-western Kuan-lung

aristocracy. Its members had served in succession the Northern Wei and

Western Wei and had then been one of a small group of powerful families

who had been involved in the founding of the Northern Chou. This group

also included the Tu-ku (the family of Yang Chien’s wife) and the Li, the

future royal house of the T’ang, and all were connected with one another

and with the Northern Chou imperial house by complex marriage ties.3

Although the Sui, seen in the light of subsequent events, marks a major

break in the continuity of Chinese history, its succession and the founda¬

tion of its empire was at the time simply a court coup which placed on the

throne one noble north-western family in place of another. The succession

of the T’ang, in its turn, simply transferred the throne to yet another of

this close-knit group of families, and throughout the seventh and early

eighth centuries the Sui royal family of Yang, the Tu-ku, and members of

the Northern Chou royal family of Yii-wen remained ubiquitous and

extremely influential.

The Sui court did not merely perpetuate the political dominance of this

small group of great north-western aristocratic clans; it also continued to

organize its empire by means of tried institutions that had been employed

under the northern dynasties for the past century. In this respect, too, the

T’ang continued along almost identical lines. There was thus a powerful

continuity, both in terms of the dominant social group, and of political

institutions, running from the Northern Wei through into the early

T’ang.

Sui Wen-ti spent the first years of his reign in consolidating in the north

the regime that he had taken over from the Northern Chou. Within a few

3 See table 4, p. xx above. See also Ch’en Yin-k’o, ‘Chi T’ang-tai chih Li, Wu, Wei, Yang

hun-yin chi-t’uan’, LSYC, 1 (1954) 33-51.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ESTABLISHMENT OF NATIONAL UNITY

5

years the Sui had produced a new legal code, reformed and rationalized

the chaotic system of local government, combined metropolitan offices

and local posts into a unified bureaucracy under strong central control,

revived the financial structure of the state, and strengthened the defences

against the Turks along the northern frontier. Like the Northern Wei and

other northern dynasties, the Sui claimed to be the legitimate rulers of all

China. Wen-ti now set about making this reality.

The conquest of the south posed quite new problems. Southern China,

at first under the Chin and later under a series of shortlived dynasties, the

Sung (420-79), Southern Ch’i (479-502), Liang (502-57) and Ch’en

(557-89), had gone its own way for two centuries. Ruling from their

splendid and luxurious capital Chien-k’ang (modern Nanking) all of these

dynasties were dominated by a small group of powerful aristocratic

families and by their generals. They were politically unstable, their regimes

a constant succession of court intrigue, coups and usurpation. They had

from time to time attempted to reconquer the north, but with disastrous

results. The centre of the southern dynasties was in the lower Yangtze

region, but during these centuries their main achievement was the

beginning of Chinese colonization in the area south of the Yangtze, and

the pacification and assimilation of its aboriginal population.

Although the political regimes were weaker than those in the north,

the south was in some ways more advanced than northern China. Its great

families, mostly ёп^гёв who had fled from the disorders in the north,

felt themselves to have a quite separate identity from the northerners,

whom they despised as crude, boorish and semi-barbarian. They con¬

sidered themselves to be the pure heirs of Han culture, and developed a

distinctive highly refined literary style, their own schools of philosophy

and of Buddhism, and their own sophisticated social mores.4 But the

differences were more fundamental than those of life-styles and rival

pretensions to be the bearers of a superior culture.

The dislocations of the third and fourth centuries had had deep and

lasting social and economic consequences in the north. Great numbers of

people had fled, especially fiom the north-west, to seek refuge and a new

life in the comparatively peaceful regions of Szechwan and the Huai and

Yangtze valleys. Millions more had perished in the constant warfare of

the fourth century. Large areas of the north were devastated and de¬

populated, and had fallen out of cultivation, so that the northern regimes

were constantly attempting to encourage their population to keep land

4 On the cultural differences between the southern and northern elites, see Moriya Mitsuo,

‘Nanjin to Hokujin’, Toa Romo, 6 (1948) 36-60, republished in his Chiigoku kodai ka%pku to

кокка (Kyoto, 1968), pp. 4:6-60.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

6

INTRODUCTION

in profitable use. Slavery had re-emerged on a large scale under the Toba,

again causing social dislocation. Much of the north had reverted to self¬

sufficient farming, and society tended to cluster in small local units domi7

nated by one or more large clans. Trade and commerce had languished

and the use of money fell away. The northern regimes designed their

institutions for this type of situation; they collected revenue in kind,

and most of the minor functions of government were performed as labour

services.

The south, once the land had been cleared, was far more fertile and

productive than the north, and the transplanting method of rice cultiva¬

tion widely in use in southern agriculture enabled it to produce considerable

surpluses. Trade continued to flourish, as did the use of money. The

southern regimes taxed commerce, and money played a comparatively

important role in their financial systems.

The actual conquest of the south by the Sui was comparatively easy.

At this time there were two southern regimes. The Later Liang, in

modern Hupei province, had been a client state of the Northern Chou

and was easily overwhelmed in 5 87. The rest of the south and south-east

was the territory of the Ch’en, based on Chien-k’ang. This too was

conquered in 589 after a short campaign, and the reunification of the

empire was complete. The actual conquest was achieved with the minimum

of bloodshed and destruction. It was consolidated by liberal and imagin¬

ative policies which achieved the allegiance of the southern ruling class,

and their incorporation into the Sui bureaucracy, while the ordinary

people were not saddled with excessive burdens, or brought fully under

the northern land and tax systems. By the early seventh century the south

had become an important source of wealth and of reserves. Under the

second Sui emperor, Yang-ti, a canal network was constructed linking

the Yangtze valley with the Huang-ho and with the area near modern

Peking, which allowed the Sui to use supplies from the south to provision

its great capital Ta-hsing ch’eng (modern Sian), and to send strategic

supplies to the northern frontier. This gave a physical form to the union

of north and south.

The reunification of China proved a solid and lasting achievement, but

the Sui itself soon fell from power. The internal stresses caused by the

establishment of its strong centralized state, the cost and loss of life

involved in its grandiose schemes of public works, the rebuilding of the

Great Wall, and the construction of canals, caused widespread suffering

and discontent. Yang-ti made matters worse by his ambitions to extend

Chinese power into the old Han territories of the north-west and into

northern Korea, now the territory of a powerful and well-organized

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ESTABLISHMENT OF NATION A L UNITY

7

native kingdom, Kogury5. A series of costly and abortive expeditions

against Kogury6 produced widespread disorders, which destroyed Sui

power. Nevertheless, after the Sui fell, although there were many con¬

tenders for power there was never any real threat that China would again

be split into a number of regional states. The question after the final Sui

collapse in 617 was which of the rebel forces would replace it as master

of the whole empire.

Events under the victors, the T’ang, confirmed this. When, after more

than a century of internal stability the rebellion of An Lu-shan in 75 j

nearly brought the dynasty to its knees, the strong highly centralized

regime founded in the seventh century proved unable to survive, except

by compromising with the powerful forces of local autonomy released by

the rebellion. Some of the richest and most vital areas of China became

virtually independent of central control. But they made no attempt to

assert their independence by setting up regional states, and were content

to remain within the framework of a united Chinese polity.

Eventually in the late ninth century massive discontent led to the

disastrous Huang Ch’ao rebellion, and the consequent fragmentation of the

country among ten or so regional regimes. These were the successors of

the provincial divisions of late T’ang times, and became independent as

much because of the total breakdown of central power as by any conscious

will of their own. Most of them were perfectly viable states, and the final

reunification of the last of them under Sung did not come about for

seventy years. Yet it was taken for granted that the empire would eventu¬

ally be reunited. In the same way, some parts of north China fell into

the hands of neighbouring alien regimes in the early tenth century, and

were to remain under foreign domination for more than four centuries.

Yet they would always be considered terra irredenta, that would be

recovered.

Political division, in short, now came to be thought of as a temporary

disturbance of the natural order of things, that would in due time be

brought to an end by the rise of a new centralized regime. After An Lu-

shan’s rebellion, when men were very conscious of the collapse of central

authority, the historical analogy which sprang to mind was not the recent

period of division, but the later stages of the Chou period when the ruler’s

authority was diminished and challenged by the power of the feudal lords.

The situation was seen in terms offeng-chien - that is decentralization and

the devolution of authority to local governors - rather than in the context

of a simple partition of the empire.

The Sui and T’ang thus finally established the idea of the integrity of

China as the territory of a single unified empire. They also, as we shall see

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

8

INTRODUCTION

below, established an outer zone of territory in which Chinese military

and political influence would remain paramount, and perhaps more im¬

portantly a quite separate zone of independent states dominated by

Chinese culture, Chinese systems of thought, literature, art, law and

political institutions, and using the Chinese written language.

INSTITUTIONAL CHANGE

The second major long-term change which came about during the Sui

and T’ang was the complete transformation of the patterns of political

life. The period from the late sixth to the eleventh century saw a complete

transformation of Chinese society and of life at every level, which is

comparable only with the earlier period of fundamental change from

500 вс to the early Han. Even historians writing in the ninth century

realized that there had been a complete change in the composition of the

governing class, and in the eleventh century Shen Kua, seeking a parallel

to the social order of the pre-Sui period, was forced to look to the alien

society of India, so different was it from the China of his own time.

In terms of modern historiography the broad problem was first set out

by Naito Torajiro on the eve of the First World War, when the Ch’ing

dynasty had fallen and China’s traditional order was finally crumbling.

To Naito the T’ang and early Sung represented the end of China’s

‘medieval’ period, and the beginning of‘modern’ China - modem in the

sense that the patterns of government, of administration and of social

organization which had then begun to take their final form were essentially

those that had survived until his own days.*

Very broadly, he characterized the changes as follows. During the long

period of division following the collapse of the Han, China had been

dominated by aristocratic groups whose social position and political

dominance at both local and national levels was unassailable. They not

only monopolized high office, but also enforced a system of selection for

officials which placed great stress on descent and social standing, and thus

entrenched their influence deeply at every level of government. They

remained a closed group, practising endogamy and marrying outside their

own group only to obtain political advantage. Some sections of this

> On Naito’s theories see H. Miyakawa, ‘An outline of the Naito hypothesis and its effects on

Japanese studies of China’, Far 14.4 (1915) 535-52; Chou I-liang, ‘Jih-pen

Naito Konan hsien-sheng tsai Chung-kuo shih-hsiieh shang chih kung-heien’, Sbib-bsueb

men-pao, 2.1 (1934) 155-72; Edwin G. Pulleyblank, Chinese history and world history,

inaugural lecture (Cambridge, 1955). Naito’s theory was first published in his Sbina Ron,

(Tokyo, 1914). It was more fully developed in his'Gaikatsu-tekiTdSdjidai kan’, Rekisbi to

ebiri, 9.5 (1922) 1-12, and in the posthumously published notes of his lectures given at

Kyoto University 1920-5, CbSgoku kinseishi (Tokyo 1947).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

INSTITUTIONAL CHANGE

9

aristocracy had intermarried with the non-Chinese conquerors of northern

China, and from this group emerged the ruling houses of the northern

dynasties of the sixth century, of the Sui and of the T’ang. Until this period

the ruling dynastic house had been little more than the particular aristo¬

cratic clan which happened to occupy the throne for the time being. The

other great aristocratic clans, which remained immensely wealthy and

powerful, treated the imperial family merely as primus inter pares. The

emperor was on close terms wijth his highest officials, who came from the

same social background and much important business was decided at

informal meetings with them. The ruler was thus forced to rule through

his fellow aristocrats, and in their mutual interest.

Under the Sui, and more particularly under the T’ang, with the whole

empire reunified a change came over this situation. The aristocracy

gradually declined in power, and its place in government was taken by

professional bureaucrats recruited by examination on the basis of their

personal talent and education, who became the agents of the ruling

dynasty rather than the representatives of their own social group. This

widened the social base of the ruling group and made office accessible to

men from lesser families. The old aristocracy gradually disappeared.

With this change in the personnel of government the position of the

emperor was also transformed. He was no longer merely first among an

aristocratic elite some of whom, as in T’ang times, might even look down

upon the royal family as social upstarts. With no aristocracy to challenge

them, and with a bureaucracy whose members were dependent upon the

dynasty for their office, power and influence, the royal clans were set

apart from ordinary society in quite a new way, while the emperor began

the gradual accretion of despotic powers which were to reach their apogee

under the Ming. The result was a growing gulf both between the emperor

and society, and between the emperor and the officials through whom he

ruled.

Naito’s theory was stated in very general terms. He was not originally

an academic historian, but a journalist and publicist who had been

involved in the study of China since the 1890s. He was writing, moreover,

when the application of modern western historical science to China’s past

had barely begun. His views have been much modified and refined by

later scholars. We now know far more than was known in his time both

about the composition of T’ang society, and about the precise nature of

political and institutional change. We know that the ‘aristocracy’ was

a far more complex social stratum than Naito imagined, and that the

changes he outlined took effect only very gradually, with their final

results becoming apparent only during the eleventh century. But the

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

IO

INTRODUCTION

general outline which Naito perceived - largely by intuitive understanding

- has stood up remarkably well to the progress of modern research.

His theory was essentially a political analysis, although he placed

political change in a broad context of social, economic and cultural

developments. His successors, particularly Miyazaki Ichisada who suc¬

ceeded to his chair at Kyoto University, tended not so much to concentrate

on political developments, but to pursue research into the broad

underlying issues of economic and social history.6 They also were at

pains to fit China’s history into a general pattern of development em¬

bracing world history. The same was true of the early generation of

Marxists, an important group which took the view that although the

late T’ang period was a major turning point in Chinese history, it was

rather the transition between a stage of slave society and one of feudalism.

To these issues I shall return later.

The next major contribution to the interpretation of the political and

institutional history of the period was the work of the great Chinese

historian Ch’en Yin-k’o.7 In two major books, published in wartime

Chungking, and in a long series of articles published in the 1940s and

195os, Professor Ch’en put forward a view of T’ang politics and institu¬

tions far more carefully researched, more closely argued and considerably

more persuasive than anything published before. His major contribution

to our understanding of the period was his analysis of the various rival

groupings and interests which provided the dynamics of T’ang court

politics. He saw the T’ang as a period of transition during which the

ruling house, itself a member of the close-knit north-western aristocracy,

presided over a court which was at first dominated by men from the same

social group, then polarized around rival regional groupings within the

aristocracy, and later divided by a constant tension between the old

aristocracy and a new class of professional bureaucrats recruited through

the examination system. The examination system was in his view a means

of providing the dynasty with a bureaucratic elite dependent upon the

dynasty for its position and authority rather than upon their noble lineage

and hereditary privilege. Both Professor Ch’en and some of his followers

attribute a large part of the rise of the examination-recruited bureaucracy

to deliberate policy on the part of the empress Wu, whom he saw as an

* For example, see Miyazaki Ichisada, Toyoteki kinsei (Kyoto, 1950).

7 The theories of Ch’en Yin-k’o were first published in two books that appeared in Chung¬

king in 1944, T’emg-toi cbeng-cbib sbibshu-lm kao and Sees T'ang cbib-tu yuan-yuan liieb-lun kao.

These have been through several later edns and are available in two recent collections of

Professor Ch’en’s writings. The extremely well-edited Cb’en Yin-k'o bsien-sbeng lun cbi (Taipei,

1971) includes only his writings published prior to 1949. A more complete, but less

thoroughly edited collection is Cb’en Yin-k’o bsien-sbeng lun-wen cbi (2 vols., Hong Kong,

1974; supplementary volume, pu-pien, Hong Kong, 1977).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

INSTITUTIONAL CHANGE

II

‘outsider’ intent upon breaking the monopoly of political power held by

the north-western aristocrats. Some very unconvincing attempts have

been made to identify these ‘new bureaucrats’ as members of a newly

emergent class of merchants and landlords.

His views have been challenged in detail: the role of the empress Wu

in the emergence of the examination stream within the bureaucracy was

certainly exaggerated, and perhaps misconceived; the new bureaucrats

were mostly recruited from the lower levels of an aristocracy far more

complex in its composition than he imagined; the factional rivalries at

court were only occasionally polarized around tensions between aristo¬

cratic groups and examination graduates and factions were for the most

part ephemeral groupings caused by a specific issue rather than the perma¬

nent alignments he envisaged; and the aristocrats maintained a greater

degree of dominance for longer than he believed to be the case.8 Neverthe¬

less, his analysis has proved an immensely fruitful starting point for later

research. In a much refined form it underlies the most important single

work on T’ang political history, Edwin G. Pulleyblank’s study of the last

years of Hsiian-tsung’s reign,9 and every chapter in this volume is deeply

indebted to his work, even when his precise views on specific issues are

challenged.

Ch’en Yin-k’o was not only concerned with the struggles between rival

aristocratic groups and court factions. He put forward equally original

and perceptive views on the development of institutions.10 Here he

identified another form of deep-rooted tension in T’ang government, the

tension arising between the institutions inherited by the Sui and the T’ang

from the northern dynasties going back to the Northern Wei, which had

as we have seen been devised for a relatively primitive and simple society,

and the demands arising from their application to the far more complex

situation of the newly reunified empire. He showed how in every field of

government the T’ang was a period of dynamic change, in which these

inherited institutions were modified or replaced by more advanced

systems more appropriate to the new circumstances.

During the past forty years a large amount of literature devoted to

such institutional changes has appeared, and it is now clear that, as in so

many other respects, the Sui and T’ang straddle two very different periods

and that very radical changes occurred in the eighth century, which are

often obscured by the continuity of nomenclature and by the survival in

8 For a survey of some of this literature see Denis Twitchett, ‘The composition of the T’ang

ruling class: new evidence from Tun-huang’, in A. F. Wright and Denis Twitchett, eds.

Perspectives on tbe T’ang (New Haven, 197}), pp. 83-5.

9 Edwin G. Pulleyblank, Tbe background of tbe rebellion of An Lu-shan (London, 1953).

10 Ch’en Yin-k’o, Sui T’ang cbib-tu уйап-ушт ШеЬ-lm kao.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

12

INTRODUCTION

name of institutions which had ceased to function and had become

sinecures. Much research still needs to be done on individual institutions

before we can confidently arrive at a general synthesis, but the main lines

that emerge are as follows.

As has been suggested above, the Sui and early T’ang were not periods

of radical institutional change or innovation. Their real achievement was

the adaptation of existing methods of administration to meet the needs of

a greatly expanded empire, and to a changed and changing social order.

It was a period of rationalization, simplification and streamlining of

procedures; of elimination of surplus posts, for example in local govern¬

ment; and of irrelevant laws. The Sui Code of 583 was a third of the size

of that in force in the Northern Chou, and a fifth of that promulgated by

the southern Liang in 503. It was also a period of codification and formal¬

ization of practice, when confidence in the permanence of strong central

government inclined statesmen to think in terms of uniform institutions

applicable to the whole empire, and of everlasting norms of social be¬

haviour, rather than to deal empirically with specific issues as they arose.

It has been conventional to consider the reign of T’ai-tsung (626-49) as

the period in which the ‘ideal institutions’ of the T’ang were formed, and

as a reign famed for its good and orderly government. Certainly T’ang

writers of the late eighth and ninth centuries looked back upon it as a

golden age. But in reality during T’ai-tsung’s reign no new institutions

emerged, nor was there any major change of government policy. The

basic structure of government, the details of administration, and the all¬

important question of the limits of government intervention had been

established under the Sui, reintroduced with comparatively minor modifi¬

cations under T’ai-tsung’s father, Kao-tsu, and embodied in the complex

of codified laws promulgated in 624.

T’ai-tsung’s real achievement was much more the further consolidation

of dynastic power, and his own very personal ‘style’ in government which

enabled him to establish a firm ascendancy over the various powerful

aristocratic groups among his high-ranking officials. His earliest historians

acclaimed him not only for his unquestioned achievement in consolidating

T’ang power both at home and abroad, but even more as a forceful and

decisive, yet fundamentally wise and benevolent sovereign always willing

to heed the counsel of his gifted group of close advisers. He was praised,

in fact, as an emperor whose exercise of power conformed to the ethical-

moral and anti-institutional ideals of conventional Confucianism, which

were shared by the members of the bureaucracy and the traditional

historians alike. His government, too, gave ample opportunities for

consultation, in daily meetings with his large group of chief ministers, to

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

INSTITUTIONAL CHANGE

*3

the upper echelons of the bureaucracy, and did much to secure their firm

allegiance to the dynasty, and also to strengthen their esprit de corps.11

The early T’ang government was simple and economical. As late as

657 there were only 13,465 ranking officials to control a population per¬

haps in excess of 50,000,000. The military establishment was kept at a

minimum by the militia, whose troops were self-sufficient farmers per¬

forming only an annual tour of duty. As many of the routine tasks of

government as possible were entrusted to selected taxpayers, who

performed them as a form of labour service. The control of the central

administration over local government, whose officials were now incorp¬

orated in a single bureaucratic service, was firmly established, and

prefectural and county posts were no longer dominated, as in the period

of division, by prominent local clans. But while central control down to the

county level was firmly maintained, it was accepted that central

policies and central intervention were practicable only in very limited areas

of activity: in the maintenance of law and order, the administration

of justice, tax collection and the allied problems of population registration

and land allocation; and the mobilization of labour for military service

and for corvde. Local implementation of government policy, since local

officials had no forces at their disposal to coerce the local population,

depended very much on compromises between the county officials and the

large sub-bureaucracy of clerks and village headmen who were both minor

employees of the state, and also representatives of the local society. The aim

was accommodation between the policies decreed in the capital and what

was feasible and acceptable locally. Too ruthless interventionist policies

were just impossible, and officials who imposed the law with undue

rigour were more likely to be censured or punished than commended.

Accommodation was thus the keynote throughout the administrative

system. In central government, the emperor was just as constrained by

the entrenched interests of the powerful aristocratic group which still

provided almost the entire upper echelon of the administration, as were

his local officials by the circumstances in which they operated.

This equilibrium did not last very long. The military ambitions of

T’ai-tsung began T’ang expansion into central Asia, and renewed attempts

to reconquer the Han colonies in Manchuria and Korea. His successor

Kao-tsung continued with these conquests, and by the 670s T’ang pro¬

tectorates had been established up to the borders of Persia, the Chinese

had occupied the Tarim and Zungharia, and destroyed Kogury6 in

Korea, although attempts to incorporate it into the empire failed. A large

11 This aspect of his administration is exemplified in H. J. Wechsler, Mirror to tbe Son of

Heaven: Wei Cbeng at tbe court of T’ang T'ai-lsung (New Haven, 1974).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

14

INTRODUCTION

and expensive defence establishment was imperative because of these

conquests, and the necessity of permanent border garrisons to protect

the empire against the traditional enemies - the Turks in the north, and

also against the newly risen and aggressive expansionist kingdom of Tibet.

At home, the bureaucracy steadily increased in size and complexity.

Expenditure increased rapidly and constantly threatened to outstrip

revenue. The tax system came under pressure and new levies had to be

introduced.

The political equilibrium at court was also shattered. T’ai-tsung’s very

personal style of administration, and the sense of common purpose that

he achieved with his bureaucracy, did not long survive him. His successor,

Kao-tsung, was a sick man who came increasingly under the dominance

of his ruthless consort, the empress Wu, who after his death controlled

the court, eventually, from 691-705 establishing herself as the sovereign-

empress (the only woman ruler in all of Chinese history) of a new dynasty.

Her regime was perhaps less disruptive of institutions than traditional

historians claimed. But her period of dominance caused very great

changes in politics. She practised a tyrannical and repressive style of

government, using secret agents and constant purges. She attempted to

eliminate the power of the imperial clan, many of whom were killed, and

she deliberately attempted to curb the power of the north-western aristo¬

cratic clans who were the dynasty’s principal supporters. By her capricious

and ruthless methods of government she destroyed the confidence of the

official class, and gave undue powers to a succession of worthless

favourites. Yet two very important developments took place. First,

officials from the great clans of the eastern plain, who had played little

part in court life in earlier reigns, began to be appointed to high office,

and the factional rivalries between different regional groups of aristocrats

ceased to be a major factor in politics. Second, and more significantly in

the long term, a bureaucratic elite who had entered service through the

examinations began to be appointed to the highest court offices.11

The examination system was not her creation. It had begun under the

Sui, and had been in use since the early years of the T’ang on a small scale.

The empress herself recruited comparatively few men through the exam¬

inations. The new situation arose partly because there was now at last a

body of officials recruited by examination who had reached the advanced

age and seniority required for high office. Moreover, she herself seems to

have deliberately chosen examination graduates for the court’s ‘pure

11 For a rather superficial account other reign, see С. P. Fitzgerald, Tbe empress ^«(London,

1956; 2nd edn 1968). See also Toyama Gunji, Sokuten Buko (Tokyo, 1966); R. W. L. Guisso,

‘ The Life and Times of the empress Wu Tse-t’ien of the T’ang dynasty’, unpublished D.Phi).

dissertation, Oxford, 1975.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

INSTITUTIONAL CHANGE

4

offices ’ (the sensitive advisory and deliberative posts), some filled by very

junior men. The examination graduates began to be employed as an elite

stream within the bureaucracy, who could expect accelerated promotion

and would spend most of their careers in central government. Most of

them came from aristocratic backgrounds, some from the great families

of the ‘national aristocracy* that had always dominated the court, others

from the equally old-established lesser ‘provincial aristocracy’ of locally

prominent clans (wang-tsu). The resulting tensions within the bureaucracy

were not so much the result of differences of class background, as Ch’en

Yin-k’o suggested, but of differences of rival functional groups within the

official structure.

When the empress Wu fell in 705 and the T’ang was restored, signs of

strain were apparent everywhere in the administration. But nothing was

done immediately, for her successor Chung-tsung proved an ineffectual

ruler, dominated by his empress who with her relatives embarked upon

an orgy of corruption, swelling the bureaucracy by the open sale of office

and of noble titles.

Under Hsiian-tsung (713-55) the dynasty was once again under firm

leadership, and reached a peak of prosperity and cultural brilliance which

marks his reign as one of the high points of Chinese history. But during

his reign the reforms necessitated by the crisis of the preceding decades

set in motion a whole complex of far-reaching changes which were to alter

radically the course of Chinese history.13

In the central administration the careful balance of powers and division

of function between the three central ministries, the Chancellery, Secre¬

tariat and Department of State Affairs, that had survived since Sui times

was destroyed. The large group of chief ministers who had served as a

rather informal advisory council to the emperor in previous reigns was

reduced to four or even less, holding broad powers both in policy-making

and as chief executives. The Chancellery and Secretariat were merged to

form a single organization formulating policy and drafting legislation on

their behalf. The Department of State Affairs became simply the executive

arm of government, and its head no longer ranked as chief minister or

participated in consultations on policy. The way was open for powerful

chief ministers to exercise almost dictatorial powers.14

The emperor ceased to discuss policy regularly with a large group of

ministers, and began to rely increasingly upon groups of young and low-

ranking secretaries drawn from the academies of scholars such as the

13 Pulleyblank, Background.

14 See Sun Kuo-tung, ‘T’ang-tai san-sheng-chih chih fa-chan yen-chiu’, Hsinya btileb-pao, j.i

(1960) 19-120; Yen Keng-wang, T'ang-sbibyen-chiu ts’ung-kao (Hong Kong, 1969), pp. 1-101;

Chou Tao-chi, Han T’ang tsai-hsiang cbib-tu (Taipei, 1964).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

INTRODUCTION

l6

Chi-hsien yuan and Han-lin yuan to help him draft documents and to plan

policy. He also began to use members of the eunuch staff of the palace as

personal agents, to circumvent the normal procedures of government.

These developments began to undermine the power and the influence of

the regular bureaucratic establishment, to break down the orderly routine

of government business, and to create a gulf between the emperor and his

officials, a gap that widened as Hstian-tsung withdrew increasingly from

public life and turned his attention to religion and the pursuit of pleasure.

Another major change came with the creation of special commissions to

deal with pressing administrative problems, especially in the financial

field. These commissions stood outside the regular bureaucratic structure;

their heads held very wide powers, and they employed large staffs, many

of them specialists. The result was a growth of specialization and pro¬

fessionalism within the bureaucracy, which eroded the ideal of a bureau¬

cracy sharing a common training as generalists who could fill any vacancy

in the official establishment, leaving specialist skills to their subordinates.15

Extensive changes in the financial system also went against the estab¬

lished ideas of uniform administration. New taxes were graduated

according to the wealth of the taxpayer, and took account of their prop¬

erty in addition to their possession of a state allocation of land. Quotas

were established for local revenues to avoid the complicated centralized

accountancy procedures of the old system. The currency was reformed, and

the transport system which brought revenues from central and southern

China was reorganized. These changes undermined the basic principles

of the simple financial system inherited from the past.16

At the same time the needs of defence against powerful and mobile

enemies led to the abandonment of the old militia system, under which

the army was mostly self-supporting, and its replacement by a professional

army of long-service troops. These were mostly stationed in the various

permanent armies on the frontier which were grouped into powerful

regional commands under military governors (cbieb-tu shih). The latter

were given overall responsibility for a strategic sector of the frontier so

that it would be possible to respond to foreign attacks more quickly and

effectively than under the old centralized system of command. In this re¬

spect the new system was successful, but it concentrated almost all

military power in the hands of a few frontier generals. Meanwhile, the

decay of the militias left the central government with little armed force

at its immediate disposal.