Tags: weapons military affairs military equipment army soviet army

Year: 1982

Text

НАС TECHNICAL INr'OOLA

4 2204, BLDG A

cngton hall station

rMGTOI, VA 22212-0051

30261308 v.8c.l

ДТС-РР-ЗШ^-ВЗ-М VHl

OFFICE OF THE ASSISTANT CHIEF OF STAFF FOR INTELLIGENT

WASHINGTON, D.C.

The Soviet Battlefield Development Plan

(SBDP)

VOLUME VIII

Missions vs Capabilities (U)

Regraded UNCLASSIFIED on

31 March 2014 Prepared by:

by USAINSCOM FOIZPA 0FFICE flF THE ASSISTANT "CHIEF 0F STAFF FOR INTELLIGENCE

Auth para 4-102, DOD 5200-1R

1 NOVEMBER 1082

WARNING NOTICE

tellioencc Sour

.hods J

IN

L)

by: Multi

Stifу on <рАОЯ

o

Classifi

Sources

ARCHIVAL COTA

DO NOT REMOVE FS.<Ki TI?

8ECRET-

1ч- >

0346

SECRET

Not fteteasatile-to 'Foreign-Nationals

AT€-?₽-2680-t}5-83-VOL VIII

(ITAC TN M8760XWP)

OFFICE OF THE ASSISTANT CHIEF OF STAFF FOR INTELLIGENCE

WASHINGTON, D.C.

The Soviet Battlefield Development Plan

(SBDP)

VOLUME УШ

Missions vs Capabilities (U)

__________AUTHORS

b6________

I b6

(Typist:! b6

DATE OF PUBLICATION

1 November 1982

Information Cutoff Date

October 1982

This product was prepared by the Red Team and approved

by the Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff for

Intelligence, Department of the Army,

WARNING NOTICE

«tfelligence Sources^

and nAathods Inprfved

(whMNreti

; Mult

orrOAOR

-(iteverse Blank)

0347

-DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY

OFFICE OF THE ASSISTANT-CHIEF-OF STAFF FOR INTELL-tGENCE

WASHINGTON.ОС 20310

RCH.YTO

ATTENTION 0Г

D AMI-FIR

1 November 1982

SUBJECT: Soviet Battlefield Development Plan <SBDP)

SEE DISTRIBUTION

1. The volume you are now reading is only one part of a multi-volume effort

titled the Soviet Battlefield Development Plan (SBDP). The SBDP is an attempt

to provide an integrated and comprehensive analysis of Soviet military think-

ing, doctrine, and combined arms force development for the present and the

future, extending out to the turn of the century. Thus, it should allow Army

doctrine and combat developers to have a Ibng-range.view of the competition

they face, so that they may design U.S. Army doctrine and forces in a dynamic

perspective. Thereby they can exploit Soviet doctrine and force modernization

to give the U.S. Army advantages in equipment, weapons, training, and tactics.

2. The SBDP is a forecast of Soviet force development for "combined arms"

operations in land warfare as we believe the Soviet "General Staff intends, it

is, therefore, not primarily a prediction but rather more an attempt to under-

stand the Soviet General Staff’s vision of the next two decades for planning

and programming. It is an attempt to provide a Soviet view, not a U.S. mirror

image. The Soviet ’General Staff does not have an "Air Land Battle" doctrine.

It has a "combined arms" doctrine of warfare under the conditions of both

conventional weapons and weapons of mass destruction. While there is much in

common between the two doctrines, the differences are far more important to

understand.

3. The basic assumption for the SBDP is the probable Soviet assumption that

there will be no significant adverse changes in the present international,

order which will cause major alterations in the Soviet development strategy

for combined arms forces. The SBDP does take into account economic and demo-

graphic constraints that are reasonably predictable by Soviet planners..

Further, it also tries to anticipate the impact of new technologies on force

development.

4. Since combined arms operations in Europe are clearly the central issue

for Soviet planners, the equipment, organizational, and operational forecasts

contained in the SBDP relate primarily to Soviet forces in the European

theater. However, since these planners must also worry about the Far East,

Southwest Asia, and power projection to non-contiguous regions, these noti-

European concerns are also treated but to a lesser degree.

This page is Unclassified

( 0348

DAMI-FIR ' 1 November 1952

SUBJECT: "Soviet Battlefield Development Plan (SBDP)

5. Because Soviet combined arms doctrine is not conceptually restricted to the

theater of operations but also concerns the "rear," that is, the entire conti-

nental USSR as a mobilization and production base, the SBDP deals with this

aspect of force planning. Preparation of the "rear" for both nuclear and non-

nuclear conflict is seen by the General Staff as the sine qua non and the first

step in an all combined arms force development.

6. The SBDP consists of eight volumes and an Executive Summary. These eight

volumes are organized to provide an interpretive framework within which to

integrate and analyze the large quantity of intelligence information we have on

Soviet ground forces.

7. The following provides a brief overview of this interpretive framework:

a. Volume I explores the ideological and historical heritage which shapes

the perspectives of Soviet military planners.

b. Volume II flows logically from Volume I showing how ideology and history

combine in the Soviet militarization of the homeland, i.e., the preparation of

the "rear” for war.

c. Volume III presents an "order of battle" listing of, and forecast for,

the ground force structure which has resulted from the ideological and histori-

cal factors reviewed in the two preceding volumes.

d. Volume IV discusses the equipment used by the forces described in

Volume III and forecasts developments in these weapons out to the year 2000.

e. Volume V discusses the present organization and operations of the ground

forces and also presents long-range forecasts in these areas.

f. Volume VI reviews high level command and control trends for these forces

and looks at how the Soviets, intend to increase their force projection capabil-

ity over the next two decades.

g. Volume VII is a study of Soviet exercises and what they might infer

about actual war missions.

h. Finally, Volume VIII is an attempt to compare Soviet missions with their

present capabilities. Such an analysis gives us a stronger sense -of the require-

ments the General Staff probably sees for building forces -over the coming decades.

8. Although the ACSI coordinated the SBDP and designed its structure, all the

major Army intelligence production organizations provided the analysis. ITAC,

FSTG. MIA, and MIIA were the primary Army contributors. [ ЬЗ Р6Г DIA

ЬЗ per DIA

iv This page is Unclassified

0349

DAMI-FIR ' 1 November Г9Й2

SUBJECT: Soviet Battlefield Development Plan (SBDP)

9. Naturally, such a comprehensive undertaking inevitably has inadequacies and

contentious conclusions in its first variant. Work on the next version is

already under way, and it is directed toward refinements, filling .gaps, and

improving the analytical forecasts. You can help us in this effort by using

the SBDP in your daily work, then answering and mailing the questionnaire

which follows this letter.

10. We are developing the 'SBDP as a tool to assist both intelligence producers

and consumers in accomplishing their tasks more efficiently and effectively.

We hope you find this and future editions of the SBDP to be of such assistance.

Major General, USA

ACofS for Intelligence

'Reverse side is blank

This Page is Unclassified

0350

CLASSIFICATION

SBDP evaluation questionnaire

1. The information requested below will help the office of. the ACSI -develop

the SBDP in a way which is most useful to the consumer. If possible, do not

detach this questionnaire. We request you photocopy it, leaving the original

in the volume for other users. If the -spaces provided for answers are not

sufficient, please type your comments on additional sheets and attach tliem to

this questionnaire form. We request all classified responses be sent through

the proper channels.

2. Please provide your name, rank or position, unit, and a short job descrip-

tion. This information will help us determine the specific way in which you

are using the SBDP.

a. NAME

b. RANK (POSITION) ______________________________________________

c. UNIT _________;_________________________________________________________

d. JOB DESCRIPTION ________________________________________________________

e. VOLUME YOU ARE EVALUATING _____________________________________________

3. Total concept and structure: Do the eight volumes of the SBDP provide the

necessary framework for effective integration and interpretation of available

information? What improvements would you suggest to the overall organization

or concept of the SBDP?

a. STRUCTURE: ___________________________________________________________

b. CONCEPT: ________________________________________________________________

vii

4_______________)

•CLASSIFICATION

0351

()

CLASSIFICATION

4. Volume structure: Is this volume well organized? Does its method of

presentation facilitate comprehension? Is the subject matter -provided in the

right degree of detail for your use? What improvements would you suggest in

these areas?

a. ORGANIZATION: _____________________________________. _______________

b. PRESENTATION: __________________________

c. DETAIL: :, -

5. Volume substance: Do you find the overall analysis and forecasts to be

sound? How would you correct or improve them?

6. These questions are "wide-scope" by design. If you have -ether', more

specific comments you wish to make concerning the SBDP please include them in

your response. Eend all responses to: ' WQDA iDAMI-FIR)

ATTN: SBDP Project Officer

WASH DC 20310

7-f; ^ti^nks for your contribution in developing the “SBDP.

0352

viii

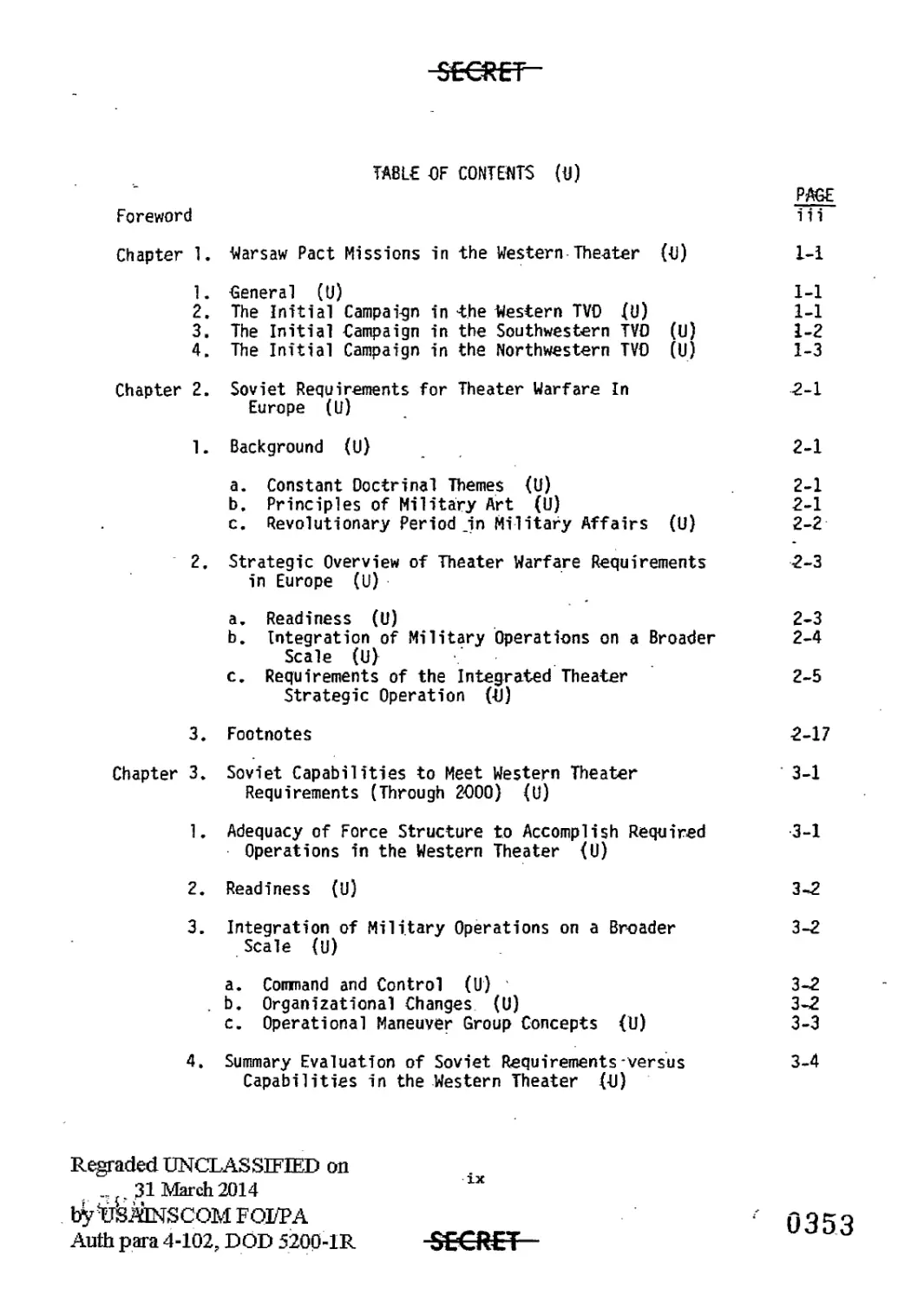

TABLE OF CONTENTS (U)

Foreword PAGE iii

Chapter 1. Warsaw Pact Missions in the Western Theater (0) 1-1

1. -General (U) 1-1

2. The Initial Campaign in the Western TVO {U) 1-1

3. The Initial Campaign in the Southwestern TVD (0) 1-2

4. The Initial Campaign in the Northwestern TVO (U) 1-3

Chapter 2. Soviet Requirements for Theater Warfare In Europe (U) 2-1

1. Background (U) 2-1

a. Constant Doctrinal Themes (U) 2-1

b. Principles of Military Art (U) 2-1

c. Revolutionary Period .in Military Affairs (0) 2-2

2, Strategic Overview of Theater Warfare Requirements in Europe (U) 2-3

a. Readiness (0) 2-3

b. Integration of Military Operations on a Broader Scale (U) 2-4

c. Requirements of the Integrated Theater Strategic Operation (-U) 2-5

3. Footnotes 2-17

Chapter 3. Soviet Capabilities to Meet Western Theater Requirements (Through 2000) (U) 3-1

1. Adequacy of Force Structure to Accomplish Required Operations in the Western Theater (U) 3-1

2. Readiness (U) 3-2

3. Integration of Military Operations on a Broader Scale (U) 3-2

a. Command and Control (U) 3-2

. b. Organizational Changes (U) 3-2

c. Operational Maneuver Group Concepts (U) 3-3

4. Summary Evaluation of Soviet Requirements versus Capabilities in the Western Theater (-U) 3-4

Regraded UNCLASSIFIED on

31 March 2014

by WdNSCOM FOLPA

Auth para 4-102, DOD 5200-1R

0353

ix

SECRET

SECRET

TABLE OF CONTENTS (Cont) (U)

PAGE

a. Introduction (U) 3-4

b. Force Structure (U) 3-4

c. 'Fielbed Technologies (U) 3-5

d. Combat Capability (0) 3-5

Chapter 4, Far East Theater (U) 4-1

1. Soviet Military Requirements (u) 4-1

2. Soviet Strategy and Capabilities (LI) 4-1

a. Conflict with China 4-1

b. Operations Against OS Forces (U) 4-2

c. Simultaneous Wars with NATO and China (0) 4-3

d. Other Contingencies (0) 4-3

3. Future Prospects (0) 4-4

a. Near Term (Through 1985) (0) 4-4

b. Mid and Far Term (Through 2000) (0) 4-4

4. Summary Evaluation of Soviet Requirements versus 4-4

Capabilities in the Far East Theater (U)

a. Introduction (U) 4-4

b. Force Structure (U) 4-5

c. Fielded Technologies (U) 4-5

d. Combat Capability (U) 4-5

Chapter 5. Southwest Asia (U) 5-1

1. Soviet Interests and Objectives (U) 5-1

2. Circumstances That Could Prompt Soviet Military 5-1

Action (U).

3. Illustrative Soviet Invasion Campaigns (U) 5-2

a. Full-Scale Invasion of Iran (U) 5-2

b. Invasion of the Persian Gulf Littoral (U) 5-5

c. Seizure of Limited Iranian Territory (0) 5-7

4. Future Prospects (4J) 5-10

a. Near Term (Through 1985) (U) 5-10

b. Mid and Far Term (Through 2000) (0)* 5-11

Regraded UNCLASSIFIED on

2014 x 0354

by USAINSCOM FOIE A

Auth para 4"102, DOD 520b_lR сел* det

SECRET

TABLE OF CONTENTS (Gont) (U)

5. Summary Evaluation of Soviet Requirements versus PAGE 5-11

Capabilities in the Southwest Asian Theater (0)

a. Introduction (4J) 5-11

b. Force Structure (U) 5t11

c. Fielded Technologies (U) 5-12

- d. Combat Capability (U) 5-12

Chapter 6. Soviet Power Projection <-U) 6-1

1. Goals, Objectives, and Policies (U) 6-1

2. Instruments of Power Projection {U) । 6-3

a. Arms Sales (U) 6-3

b. Military Advisors (U) 6-3

c. Economic Aid (0) 6-4

d. Proxies (U) 6-4

e. Treaties (U) 6-4

f. Subversion (U) 6-5

3. Soviet Forces Available for Deployment to Distant 6-5

Areas (U)

4. Other Soviet Resources for Distant Operations (U) 6-5

a. Overseas Facilities (U) 6-5

b. Merchant Marine (U) 6-6

c. Fishing Fleets III) 6-6

5. Command and Control of Distant Operations (U) 6-6

6. Capabilities for Distant Operations (U) 6-6

a. Military Airlifts (ll) 6-6

b. Aeroflot <U) 6-7

c. Intervention of Combat Forces in a Local Conflict (U) 6-7

d. Airborne Assault Operations (U) 6-7

e. Amphibious Assault Operations {U) 6-8

f. Interdiction of Sea Lines of Communication (SLOC) (U) 6-9

7. Future Force Capabilities for Distant Operations (U) 6-9

a. Navy (U) 6-9

b. Air Forces (U) 6-10

Regraded UNCLASSIFIED on

31 Wch 2014

by ШАЙШОМ FOIL A

Autii para 4-102, DOD 5200-lR

0355

SECRET

"SECRET

TABIC OF CONTENTS (Cont) (<J)

PAGE

8. Regional Outlook (XI) 6-11

a. Southern Africa (4J) 6-11

b. Zaire (U) 6-13

c. Caribbean (4J) 6-14

d. Southeast Asia (tl) 6-16

Chapter 7. Summary Evaluation of Soviet Hi 1 itary Requirements 7-1

versus Capabilities (U)

1. Introduction (U) 7-1

2. Western Theater (U) 7-2

a. Introduction (0) 7-2

b. Force Structure. (U) .. 7-2

c. Fielded Technologies (ll) 7-3

d. Combat Capability (U) 7-3

3. Southwest Asian Theater (U) 7-4

a. Introduction (U) 7-4

b. Force Structure (U) 7-4

c. Fielded Technologies (U) 7-4

d. Combat Capability (U) 7-5

4. Far East Theater (U) 7-5

a. Introduction (ll) 7-5

b. Force Structure (0) 7-5

c. Fielded Technologies (U) 7-5

d. Combat Capability (U) 7.-6

5. Global Strategy (U) 7-5

a. Introduction (U) 7-6

b. Strategic Concept (U) 7-6

Regraded UNCLASSIFIED on .

31 March 2014

by USAINSCOM FOIL A xii

Auth para4402, DOD 5200-1R

SECRET

S€€RET

CHAPTER 1

WARSAW PACT MISSi-ONS ID THE WESTERN THEATER (4J)

1. (U) General

(S/N&FORN) The Soviets appear to have divided the Western Theater into

at least four theaters of military operations (TVDs). They believe that

Central Europe, which is the focus of the Western TVO, would be the decisive

arena, and this belief is demonstrated by the priority they give to this

region when assigning military manpower and equipment. It is also evident

from Soviet doctrine and writings that, if war comes in Europe, they plan to

overwhelm NATO in Germany with a massive combined air assault and ground

offensive. This principal effort notwithstanding, the Soviets know that the

Pact must also be prepared for operations in adjacent land and sea areas

identified as the Southwestern and Northwestern TVDs and one or more

maritime TVDs. The Soviet view of how these flank operations relate to the

main thrust in Central Europe is not well defined. In a Central European

scenario, one might expect the Soviets to strike at northern Norway in

order to facilitate the deployment of their Northern Fleet, to attack NATO

naval forces in the Mediterranean, and to move against the Turkish Straits.

Secondary offensives or holding operations probably would be conducted on

the flanks of these primary operations in order -both to weaken NATO forces

in these areas and to keep them from being shifted to Central Europe.

2. (U) The Initial Campaign in the Western TVD

a. (5/N^ORN) Warsaw Pact planning for the Western TVO envisions

offensives along three axes in Central Europe. To carry out these offen-

sives, the Pact probably would seek, at least initially, to organize its

forces into three corresponding fronts: the Soviet-East German front, the

Polish Front, and the Czechoslovak-Soviet Front. These fronts would be

made up of varying combinations of Soviet and non-Soviet Warsaw Pact (-NSWP)

forces stationed in East Germany, Poland, and Czechoslovakia. If time per-

mitted, these fronts would be reinforced by two additional fronts--

Belorussian and Carpathian Fronts—drawn from military districts in the

western USSR. Although a war between NATO and the Warsaw Pact could evolve

in several ways, it probably would he preceded by an extended period of

rising tension during which both sides take steps to improve their force

posture. The Pact would require 2 to 3 weeks to prepare the. five fronts

discussed above and move them into assembly areas. The force -assembled

would consist of 80 to 90 ground divisions plus support and tactical air

units, and there would be time for most of the active Warsaw Pact naval

units to get ready to put to sea. To launch an offensive in Central Europe

with less preparation time but also with less than five fronts is, from a

Soviet standpoint, feasible but not desirable.

b. (S/N^PoRN) The Soviet-East German front would attack NATO forces in

Regraded UNCLASSIFIED on

31 March 2014

by USAINSCOM FOIZPA

Auth para 4-102, DOD 5200-1R

035?

SECRET

central West -Germany, probably between Hannover and Mannheim. Major

elements of this front mi-ght swing north of Hannover across the North German

Plain, but this would demand extensive restructuring of its logistic base.

The Polish front would attempt to defeat NATO forces i-n northern West

Germany and seize Denmark and the Netherlands. The Czechoslovak-Soviet

Front would attack toward the Rhine in the area roughly between Mannheim

and the Swiss-German border. If the two additional.reinforcing fronts from

the USSR were available, the Belorussian Front would probably be committed

alongside the Soviet-East German Front, probably on its southern flank.

The Carpathian Front probably would be used to reinforce the Czechoslovak-

Soviet Front.

(«)

c. fS/NOFORN) The success of a Warsaw Pact campaign in Central Europe

would depend to a considerable degree on the performance of the NSWP forces

involved. Recent events in Poland provide new reasons to question the

reliability of these forces, and the Soviets might therefore be planning to

accept a larger role in a Central European offensive, particularly in the

northern part of Germany. Poland continues to bear the principal responsi-

bility for operations on the northern axis of advance for facilitating the

movement of Soviet reinforcements toward West Germany. There is no evidence

that the Soviets have decided to relieve the Poles of these responsibilities,

but alternative plans must have been considered. One option would be to

bring forces forward from the USSR's Baltic Military District to operate

jointly with the Polish armed forces.

d. (S/NOrORN) In the Baltic Sea, Warsaw Pact naval forces would

operate as part of the overall campaign in the Western TVD, particularly in

conjunction with the ground and air operations of the Polish Front. Their

broad objectives in this area would be to gain control of the Baltic Sea

and access to the North Sea. If initial sea control and air superiority

operations were successful, Pact forces in the Baltic would concentrate on

supporting the Polish Front's offensive across northern West Germany and

into Denmark.

3. (U) The Initial Campaign in the Southwestern TVD

a. (-S/NO^RN) The Southwestern TVD encompasses a broad area reaching

from Italy to the Persian Gulf. The principal focus of the Southwestern

TVD is on a war with NATO, in which it would conduct operations in conjunc-

tion with the Western and Northwestern TVDs. first among the Pact’s objec-

tives in this campaign would be the seizure of the Turkish Straits. The

Soviet forces for this operation would be drawn chiefly from the. Odessa

Military District, and most of them would have to cross Romania and Bulgaria

to reach Turkish territory. In Bulgaria, they would be augmented by some

Bulgarian forces to form an Odessa front whose objectives would be to

destroy Turkish forces in eastern Thrace, break through the fortifications

protecting the land approaches to the Turkish Straits, and seize the

Straits’. . -

Regraded UNCLASSIFIED on

31 Mareh2014

by USAINS COM FOIZPA

Autii para 4-102, DOD 5200-lR

1-2

0358

SECRET

SECRET

b. (S/NGE6RN-) Probably concurrent with the effort to seize the Straits

would be a major ground operation through Austria. The attack would tie con-

ducted by a combined Soviet and Hungarian force, forming the Danube front,

which could also be used to protect the southern flank -of the Western TVD

in West Germany or could move south into Italy.

(u)

c. (-5/N6F0RN) To attack Greece, the Pact would form a Balkan Front -on

the western flank of the Odessa Front. It would consist of the bulk of the

Bulgarian Army and could include some Romanian forces. -Because of the size

of the Balkan Front, the difficult terrain in Greece, and the jquesti-onable

commitment of Romanian forces, it seems likely that this front would be

used only to engage Greek forces in Thrace and to secure the western flank

of the Odessa Front.

d. (S/N^ORN) The Warsaw Pact could conduct a limited offensive into

eastern Turkey, the primary objective of which would probably be to keep

Turkish forces in this area from aiding in the defense of the Straits. The

Soviet forces available for this offensive would be drawn from the

Transcaucasu.s Military District and, if required, from the North -Caucasus

Military District. Part of this combined force might also be used to move

into northwestern Iran and, conceivably, farther south. Although control

of this area would be attractive, the effort to seize it—either as a pre-

lude to or in conjunction .with a European war—could tie up considerable

second-echelon and . strategic reserve forces that otherwise would be

available for use against NATO.

e. (5/NCirORN) Naval operations to support and extend the Warsaw

Pact's ground offensives in the Southwestern TVD would include efforts to

consolidate control of the Black Sea, support the movement of Pact forces

along its western shore and assist in seizing the Turkish Straits. From

the outset of hostilities, Pact air and naval units would attack NATO naval

forces in the Mediterranean, and possibly in the Arabian Sea, especially

carrier battle groups and ballistic missile submarines.

4. (u) The Initial Campaign in the Northwestern TVD

(S/NO^nN) Initial Soviet objectives in this theater would be to

ensure the security of Northern Fleet ballistic missile submarines,

guarantee access to the North Atlantic for these and other Soviet ships and

aircraft, and protect the Kola Peninsula and the Leningrad гедтюп* To

achieve these objectives, the Soviets almost certainly would launch a

limited ground offensive into northern Norway early in the war. The

Soviets probably would be deterred from attempting a larger campaign into

central or southern Norway early in the war by the difficult terrain,

potentially strong NATO resistance beyond Finnmark, and extended lines of

communication from the Pact interior.

Regraded UNCLASSIFIED on

31 March 2014

by USAINSCOM FOI/P A

Auth para 4-102, DOD 5200-1R

NOTE: The.reverse aide of this 1-3

page i> blank.

SECRET

0359

SECRET

CHAPTER 2

SOVIET REQUIREMENTS FOR THEATER WARFARE IN EUROPE (4J)

1. (U) Background

(U) The Soviets' requirements for successful theater warfare in Europe

have evolved gradually, in parallel with the development of military capa-

bilities on both sides. These evolving requirements are also deeply rooted

in Soviet doctrine, principles of military art, and historical experience.

a. (U) Constant Doctrinal Themes. As elaborated in Volume! of the

SBDP, Soviet military, doctrine has tended to be stable, and hence to lend

stability to force development. The main features of this doctrine include

the expected decisive nature of future war between socialism and

capitalism; the likelihood that this war will become nuclear; the probable

decisive role of nuclear weapons; the need for massive “multi-mi 11 ion man"

armies; the highly dynamic, unstable nature of the modern battlefield,

requiring extremely violent, fast-paced campaigns; the capability to wage

war successfully in either a nuclear or non-nuclear environment; and the

need to exert maximum simultaneous offensive pressure throughout the depths

of the enemy’s territory. It is reasonable to expect these constant

doctrinal themes to remain intact thru the year 2000. This assumption

clarifies to some extent uncertainities about the nature of the year-2000

battlefield. For example, the Soviets are not likely to discard their con-

cept of a massive conscript army in favor of a small, professional force,

or to cease to give priority to the demands of fighting on an "integrated"

battlefield. It also argues strongly that force developments will continue

to be keyed to a maneuver-oriented, fast-paced, offensive campaign.

b. (U) Principles of Military Art. Besides general doctrinal pro-

nouncements about the nature of the future war they must prepare to fight,

Soviet requirements may be inferred from their principles of military art.

These principles are modified periodically to keep them compatible with the

latest perceptions of the modern battlefield, although in practice they

have considerable continuity. The most important of the principles are the

following:

(1) (U) High combat preparedness (boyevaya • gotovnost') to

accomplish the task regardless of the circumstances under which the war is

initiated or prosecuted;

(2) (U) surprise (vnezapnost’), decisiveness, and activeness of

combat actions;

{3) <U) constant effort to seize and retain the initiative;

(4) (il) complete utilization of the various means and methods of

combat to achieve victory;

Regraded UNCLASSIFIED on 2-i

31 March 2014

by pSAINSCOM FOIZPA

Auth para 4-102, DOD 5200-lR StCRtT

0360

SECRET

(5) (U)' -coordinated use and close coordination of formations

(large units) of all armed services and branches;

(6) (U) decisive concentration of the main efforts at the right

moment, on the most important axes, to solve the main tasks;

(7) (U) simultaneous destruction of the enemy to the full depth

of his formation, timely intensification of effort, bold maneuver of forces

and means for development of combat actions at high tempos, and defeat of

the enemy in a short time;

(8) (li) calculation and full utilization of the moral-political

factor;

(8) (d) firm and continuous control (upravleniye);

(10) (U) determination and decisiveness in accomplishing the

mission;

(И) (II) thorough support of combat actions;

(12) (U) timely restoration (vosstanovleniye) of reserves and

combat effectiveness of the forces.^

c. (U) Revolutionary Period in Military Affairs, The above doctrinal

tenets and principles of military art themselves represent general require-

ments. Although they have had, and are expected to continue to have, con-

siderable continuity, they are not considered permanent. Marxist-Leninist

dialectics assert that military affairs (as are all other phenomena) are in

a state of constant evolution, with the future flowing from the present,

which in turn had its roots in the past. This natural state of continuous

change in military affairs results primarily from, changes in weapons and

military technology. The Soviet leadership believes that a revolutionary

transitional period in military affairs is now under way. This revolution

is the result of a combination of numerous breakthroughs in weaponry and

military technology that have occurred in recent years or are now on the

. verge of occurring. The pace of changes brought about by new technology is

seen as accelerating, and the leadership is vitally concerned with staying

abreast by making the necessary adaptations in a timely fashion. In this

context, overcoming natural bureaucratic tendencies toward preparing to

"fight the last war" is of concern. The importance of all these issues may

be seen in this quotation from MSU Ogarkov's 1982 booklet:

"A deep, in the full sense revolutionary, upheaval in military affairs

is occurring in pur time in connection with creation of thermonuclear

weapons, the vigourous development of electronics, development of weapons

based on new physical principles, and also in connection with broad quali-

tative perfecting of conventional means of armed conflict. This in turn

influences all other sides of military affairs, first of all on the deve-

lopment and perfecting of forms and methods of military actions, and

Regraded UNCLASSIFIED on

31 March 2014

by USAINSCOM FOIZPA

Auth para 4-102, DOD 5200-1R

2-2

0361

SECRET

SECRET

consequently, -on .the organi-zatinnal structure -of troops (forces), of the

navy, on perfecting systems -of armament and control organs. .

"Realization -of this dialectic process is especially important in the

contemporary stage when on the basis of scientific-technical progress the

fundamental systems of armament are being renewed practically every 10-12

years. In these conditions untimely changing of views, stagnation in deve-

loping and putting into practice new issues of military development are

fraught with serious consequences."-2 The following section will present a

more detailed description of Soviet requirements as gleaned from writings,

exercises, and force development trends. These requirements represent

significant current issue areas to Soviet commanders and planners; they have

been the subject of considerable attention.

2. (U) Strategic Overview of Theater Warfare Requirements in Europe

a. (S/NOTO^?/WNINTEL) Readiness. The Soviets are concerned about

reducing the time in which Warsaw Pact forces can convert from peacetime to

wartime readiness. This encompasses several tasks. Reduced strength and

cadre unit readiness requires improvement, including periodic exercises at

high levels of personnel strength. Alerting and mobilization of forces must

be accomplished more rapidly, and the resiliency and autonomy of the mobili-

zation system must be improved. Faster deployment into staging areas and

battle positions is required. The ability of missile units to fire while

moving to alert positions and during short halts requires improvement. The

system for providing replacement personnel, especially officers and critical

specialities, must be strengthened in light of more sober assessments of the

results of nuclear strikes. This is to include enlarging the reserve struc-

ture, with special attention to replacement command and control entities.

All of these efforts are designed to produce a force able’ to shift effi-

ciently and quickly to a wartime posture, regardless of how the war might

begin. Backing up the military organizaton, the entire national economy

must be made more responsive to the war-fighting requirements of the armed

forces. This requirement was expressed by MSU N. =Qgarkov, Chief of the

Soviet General Staff, who wrote in a recent Kommunist article:

"The question of the timely transfer of the Armed forces and the entire

national economy onto a war footing and of their mobilization in a short

time is considerably more acute. That is why the supply of trained person-

nel reserves and hardware to troops predetermines a need for measures

planned accurately in peacetime and for coordinated actions by party,

soviet and military organs on the spot."

"Coordination in the mobilization and deployment of the Armed forces

and the national economy as a whole, particularly in using manpower,

transportation, communications and energy and in ensuring the stability -and

survivability of the country's economic mechanism, is now needed more than

ever. In this connection a constant quest is needed in the sphere of

improving the system of production ties of enterprises producing the main

Regraded UNCLASSIFIED on

31 March 2014

by USAINSCOM.FO1ZPA

Auth para 4-102, DOD 5200-lR

2-3

SECRET

0362

SECRET

types of weapons,' of enhancing, in the event of war, the autonomy of pro-

duction enterprises and associations in terms of energy and water supplies,

of completely providing them with the necessary stocks, and of creating a

reserve of equipment, and materials. The actual system of the national

economy's mobilization readiness also needs further improvement, proceeding

from the premise that the close interconnection between the mobilization

readiness of the Armed Forces, the national economy and civil defense is a

very important condition for maintaining the defense capability of the

country as a whole at the proper level."3

b. (-U) Integration of Military Operations on a Broader Scale

(1) (U) The focal point of Soviet efforts to modernize military

art in order to keep pace with scientific and technical progress is the

adoption of a broader, more encompassing viewpoint on integrated theater

operations. This endeavor also has received the attention of Marshal

Ogarkov:

"It is known that during the great patriotic war the basic form of

military operations was the frontal operation. Here, as a rule, the front

advanced over a zone of 200-300 km on average, to a depth of between 100

and 300-400 km. After the completion bf the front operation there was

usually a lull, and not infrequently a prolonged period of preparation for

the next frontal operation. At the time that was entirely necessary and

justified and was in accordance with the means of destruction then

available."

"Now the situation is different. The front's command has at its

disposal means of destruction (missiles, missile-carrying aircraft and so

forth) whose combat potential considerably transcends the bounds of front

operations."

"There has been a sharp increase in the maneuverability of troops; and

the methods of resolution of many strategic and operational tasks by

groupings and formations of branches of the Armed Forces have changed. As

a result earlier forms of use of formations and groupings have largely

ceased to correspond to the new conditions. In this connection it is evi-

dently necessary to regard as the basic operation in a possible future war

not the frontal form, but a larger-scale, form of military operations—the

theater strategic operation."^

(«)

(2) (S/NOryRN/Wfi INTEL) The watchword of this requirement is

integration. {t is applicable across the full spectrum of combat tasks.

The Soviets have embarked on a long-range effort to more fully integrate

military operations into what they term the theater strategic operation.

Some of the principles of operational art, that is of the conduct of army

and front level operations, have been modified to correspond to the

changing perceptions of theater warfare requirements. Combat operations in

the Western TVD are to be integrated into a. single campaign. The operations

Regraded UNCLASSIFIED on

31 March 2014

by USAINSCOM FOKPA

Auth para 4-102, DOD 5200-1R

2-4

SECRET

0363

-SECRET

of fronts are to be orchestrated at the level of the theater of military

operations (TVO) and are to be conducted without pause until the entire

campaign is concluded. Each front may be required to conduct two or more

operations in succession with little or no lull between operations. Ongoing

modifications to operational art are intended to upgrade the capability

to conduct such a campaign. in part, these modifications reflect a

concerted effort to bring operational art up to a level commensurate with

modern weapons and equipment: to more fully use their inherent capabili-

ties. It is also motivated by recognition of improved Western defensive

capabilities—actual and potential--which has prompted concern for finding

new methods to accomplish traditional functions more effectively and effi-

ciently. Finally, the elaboration of new elements of operational art is

intended to serve as a guide to force, training, and doctrine development.

c. (U) Requirements of the integrated Theater Strategic Operation.

This section will sketch the Soviet perception of what is required to carry

out this integrated theater strategic operation, noting significant modifi-

cations in operational art. Subsequent sections will detail important

facets of the operations.

(u)

(1) (S/NOFORN/WN1N-TEL) General. A successful integrated theater

strategic operation requires the ability to mass combat power on the criti-

cal axes, at the critical times, and the flexibility to change the locus of

effort quickly in order to take advantage of rapid changes in the battle-

field situation. The Soviets speak of the need to orchestrate the massive

theater campaign so effectively that the enemy is literally overwhelmed,

unable to react adequately to counter the pressure, and collapses under the

onslaught. Stress is placed on the need to conduct continuous operations,

and to do so simultaneously throughout the depths of the enemy's opera-

tional formations.

(2) (U) Historical Precedents—The "Peep Operation." This concept

of simultaneous, deep operations is a fundamental tenet of Soviet opera-

tional art, dating back to the 1930s when the “deep operation" {glubokiy

boy) was first elaborated by Soviet theoreticians. At that time, the

Soviets concluded that the main task was to overcome the problem created

when forces had broken through enemy defenses and were spent by the effort,

and thus were unable to exploit their gains or even hold the ground they

had won. The deeper an army moved into the enemy's formations, the more

difficult it became for that army to continue its attack, and the more

readily could the enemy bring his reserves to bear on the attacking force.

Four prerequisites for the successful conduct of deep operations, were

recognized. These are, the capability to reliably suppress the enemy to

the depths of his operational formation, thus preventing him from adequately

focusing power on the sector under attack; to penetrate his -defending

forces; to rapidly exploit the penetration into his -operational rear area;

and to isolate that portion of the battlefield from outside reinforcement.

These requirements guided ’Soviet force development and operational art to

the end of World War II, and have remained conceptually unchanged to this

Regraded UNCLASSIFIED on

31 March 2014

by USAINSCOM FOJZPA

Auth para 4-102, DOD 5200-1R

2-5

SECRET

0364

-SECRET

day. They led in the 1930s to the creation of separate tank formations, or

"mobile groupings”, whose primary purpose was to "turn tactical into opera-

tional success" by exploiting breakthroughs attained by rifle troops.

Multiple echelons.of troops were created to overcome the problem of loss of

momentum, by providing the means to build up offensive pressure at that

critical period when the fighting was being done in the depth -of the

enemy's formations.

(3) (0) Post-War Innovations. Following World War II, the

Soviets reaffirmed the concept of the deep operation and began the process

of motorizing their rifle troops to enable them to operate better with tank

formations. Soviet acknowledgement of the primacy of nuclear weapons pro-

duced the only major doctrinal change since the 1930s and led to the re-

making of the Soviet armed forces to fight on the nuclear battlefield. The

combination of nuclear weapons, missile delivery means, and guidance and

control systems was said to have produced a "qualitative jump," which they

called a "revolution in military affairs." The zenith of the Soviet fixa-

tion on the exclusively nuclear battlefield was reached in the 1960s.

Numerous writings, including all three editions of Sokolovskiy's Military

Strategy, issued in 1962, 1963, and 1968, affirmed the preeminent role of

nuclear weapons in modern warfare. Throughout.this revolution in doctrine,

however, the primacy of the deep operation was not challenged. The Soviets

saw the use of nuclear weapons on the battlefield as a means to further

their ability to conduct deep operations since they would enable a military

force, for the first time, to simultaneously and decisively influence the

battlefield throughout its "operational and strategic depth". No longer

would it be necessary to penetrate enemy defenses in succession in a time-

consuming procedure. Nuclear weapons would accomplish the roles of

suppression, breaking through enemy positions, and deep interdiction stri-

kes, thus reducing the need for conventional artillery and air strikes and

facilitating rapid advance by tank-heavy ground force formations deep into

the enemy operational rear. The future battlefield was envisioned as dyna-

mic and highly mobile, without stable front lines and with a blurred

distinction between front and rear. Nuclear weapons provided greater

opportunities for delivering surprise strikes against both troops and deep

rear areas.

(4) ({J) Adaptation to the Integrated Battlefield. In the late

1960s, Soviet writings began to discuss the combination of battlefield

nuclear weapons with perfected conventional armaments. This led, by the

early 1970s, to a minor but important doctrinal modification that accepted

the "possibility" of conducting combat actions by units and sub-units

(regiments, battalions, and companies) with conventional weapons. The

doctrinal pronouncement noted that conventional weapons alone might be used

in the initial phases of a~ world war, and that it would be -necessary to

employ conventional weapons during and between nuclear exchanges. At this

time, Soviet forces were formally charged with the mission of fighting with

or without nuclear weapons. The basic concept of deep operations remained

essentially, unchanged, although the term had fallen into disuse. Soviet

Regraded UNCLASSIFIED on

31 March 2014 2-6

by USAINSCOM FOIL A

Auth para 4-102, DOD 5200-1R сггпгт

SECRET

0365

-SECRET

ground forces were steadily improved to permit them to better carry-out the

preferred rapid and deep mobile operations. The problem of achieving

simultaneous influence throughout the depths of the battlefield, which had

been overcome through the use of nuclear weapons, remained inadequately

solved in a conventional environment.

(u)

(5) (S/N0F0IWWN INTEL) Recent Organizational Changes. By the

late 1970s, a comprehensive review of the. requirements of theater warfare

under modern conditions seems to have occurred. Changes in organization of

air, air defense, and ground forces, took place, all apparently designed to

permit better execution of the integrated theater strategic operation under

either nuclear or non-nuclear conditions. Bomber and longer range tactical

aircraft were operationally integrated to form the core of the strike force

for major theater strategic air operations. Previously separate and auto-

nomous air defense elements were unified into a single centralized struc-

ture within each military district or wartime front. This reorganization

permits better coordination of an integrated theater-wide air defense plan.

The rapid growth of attack helicopter forces under front control signifi-

cantly improves fire support to combined-arms and tank armies, while the

formation, since 1979, of air assau-lt brigades at front level demonstrates

the requirement for more air assault operations in support of advancing

ground forces. Reorganization of both tank and motorized rifle -divisions

reflects an across-the-board effort to more effectively conduct fast, con-

tinuous operations of great spatial scope in the face of anticipated NATO

air, air defense, anti-tank, and other improvements. They have been accom-

panied by increased requirements for all aspects of theater operations, as

discussed below..

(u)

(6) {5/NOFORN/WNINTEL) Maneuver. Operations by fronts and armies

are to be focused on major theater axes. Greater agility in concentrating

efforts on first one and then another major theater axis is sought through

enhancing the ability to regroup major air and ground formations over

longer distances.

(u)

(a) (S/NOFORN/WNINTEL) Breakthrough Operations. A more

modern breakthrough operation is required that employs more flexible and

more rapid methods and broader integration across the front. This opera-

tion must increasingly substitute rapidly deployable force for massing of

troops. A solution to this requirement is being approached gradually

through the integration of air power, air mobility, and fires from mobile,

dispersed artillery, with ground maneuver forces brought forward rapidly

from the depths to quickly concentrate on multiple axes and just as quickly

disperse.

(b) (U) Exploitation. Improvement to exploitation operations

is also required. They must be made more rapid and continuous in order to

more quickly, carry the battle deep into the enemy operational rear.

Fulfilling this requirement involves careful coordination of maneuver, fire

support, air defense, and logistics elements.

Regraded UNCLASSIFIED on

31 March 2014

by USAINSCOM FOEPA

Auth para 4-102, DOD 5200-1'R

2-7

SECRET

0366

SECRET

. (5/NOrORN) With regard to maneuver,. the continuing

development of operational maneuver group {t)MG) concepts has been the cen-

terpiece of efforts to improve the effectiveness of exploitation operations.®

The OMG has historical antecedents in the operations of "mobile groups" in

World War II, although these earlier concepts were discarded in Soviet mili-

tary theory following the war, when mechanization of rifle units seemed to

eliminate the need for special mobile units. The current establishment of

OMG is part of the Soviet response to the requirement to enhance capabili-

ties for deep operations in the face of improvements in the NATO defense.

2. (-SfiiOFORMyWN'INTEL) OMGs of division to army size

are expected to move behind leading attack echelons. As early in the

offensive as possible, probably before second echelon divisions and armies

are introduced, OMGs would attempt to drive through gaps and weak sectors

in NATOs defense toward objectives deep in its operational rear. (i.e.,

the NATO corps rear area). OMGs would seek to rapidly destroy NATO nuclear-

weapons and reserves, prevent lateral reinforcement, and destroy supply

lines and C^I , through a series of large raiding operations. Helicopters

would be a primary source of air support to the OMGs, conducting route

reconnaissance, assisting in command and control, and providing fire sup-

port at the objective. Helicopters also would be useful in moving air

assault brigade elements forward of the FEBA to enable their close interac-

tion with the OMGs. The coincident creation of air assault brigades indi-

cates that their employment with OMGs is likely. 'OMG operations within the

NATO rear area would be relatively autonomous, although subordinate to the

overall front operations plan. All of this activity seems designed to

increase the tempo of the advance, disguise the axis of the main effort,

draw off enemy reserves, and in general disrupt enemy operational stabi-

lity. OMG employment could present NATO commanders with a difficult .deci-

sion as to whether to commit significant forces against the OMGs, thereby

diminishing the amount of force available for commitment against the main

body and risking collapse of the defense.

(u)

(c) (5/NOFORN/-WN INTCL) Improvements in Tactics. At lower

levels, there is a requirement t-o improve maneuver tactics to meet the

increased demands posed by enhancements to operational art. Some recurring

themes for tactical improvement include searching for better ways to combat

antitank defenses, improving coordination with aviation {especially

helicopter aviation) and artillery, developing better methods for over-

coming areas of mass destruction, obstacles, mountain passes and other

barriers, and improving specialized maneuver forms that are roughly analo-

gous^ at the regimental and divisional level, to t)MG operations.- The

latter include operations of forward, raiding, and enveloping detachments,

and the wide use of tactical air assault operations (parachute and

heliborne) in tandem with advancing ground forces. Night offensive, combat

operations, especially by forward and raiding detachments, are to receive

more emphasis. These measures are all intended to improve the overall

speed and agility® of maneuver divisions and regiments and thereby

contribute to maintaining the pace of advance.

Regraded UNCLASSIFIED on

31 March 2014

by US.MNSCOM FOIZPA

Auth para 4-102, DOD 5200-lR

2-8

SECRET

0367

SECRET

(7) (U) Airborne, Air Assault, Airmobile Assault Forces

(a) (JJ) The Soviets will retain a full spectrum -of specialized

units for. insertion by fixed-wing transport and/or helicopter into both the

enemy combat and rear areas. These specialized units will continue to be

supplemented by the airlanding of regular motorized rifle troops as the

specific operational situation warrants.

(u)

(b) (S/NOrOilN) Air assault requirements will continue to be a

major area of focus.. The front organic air assault brigade's current pri-

mary role is to support the advance of an army-size front operational

maneuver group in the deep rear. The Soviets are likely to add to this

role by organizing, in many armies, separate air assault battalions whose

primary mission would be to support the advance of division-size army

operational maneuver groups. Air assault units might be incorporated into

the tank division to replace some motorized rifle units.,

(u)

(c) (-5? Airborne divisions are likely to continue as centrally

controlled assets of the Supreme High Command to carry out deep strategic

missions in support of theater offensive goals. Some divisions will be

subordinated to individual fronts to carry out operational landings to

accomplish missions in support of the goals of individual front offensive

operations. .

. (u)

(d) (S/NorORNj Airmobile assault brigades may continue io

exist in some fronts opposite the Near East and Far East regions, possibly

because of terrain. Shallow airmobile landings in the tactical zone of the

enemy defense will probably continue to be the responsibility of motorized

rifle companies and battalions drawn from regular combat divisions. This

function may be enhanced by making helicopter lift organic to the existing

division-or by replacing some motor rifle units with specialized air

assault units in a few divisions.

(u)

(8) (S/NOTORN/WNi-NfEL) Artillery Fire Support. The Soviets are

seeking more flexible and more responsive fire.support capable of bringing

a high volume of fire to bear rapidly on multiple, often fleeting, targets.

Key considerations include the integration of artillery fires with all

other, means of destruction, integration of nuclear with non-nuclear fines,

automation of the fire control system, achieving a smooth transition from

one phase of support to another, improving ability to attrite enemy

nuclear-capable and . supporting systems, better antitank suppression, and

improved efficiency of ammunition consumption.

(u)

(a) (S/NGTOftN/WNiNTEt) Integration of All Non-nuclear Fires.

The integration of all available conventional means of destruction into a

single, flexible concept and plan remains a long-term Soviet requirement.

We believe that rocket troops and artillery, front and army aviation, air

defense assets (especially for anti-helicopter defense), tanks and ICVs,

and radioelectronic warfare assets are all to be included in such a unified

Regraded UNCLASSIFIED on

31 March 2014

by USAINSCOM FOIZPA

Auth para 4-102, DOD 5200-1R

5-9

SECRET

0368

plan. The wider incorporation -of necessary automation and other sophisti-

cated command and control capabilities will more fully resolve this

requirement. A basic goal, in keeping with the Soviet emphasis on deep

operations, is -a near-simultaneous destruction capability throughout the

entire enemy operational and tactical depth.

(u)

4b) (S/NOrORN/WNINTEL) Integration of Nuclear and Non-nuclear

Fires. Soviet rocket troop and artillery fire planning seeks to be respon-

sive in an integrated nuclear and non-nuclear battlefield. This requires

the ability to organize a system that is suitable for the heavier artillery

fire support responsibilities of the non-nuclear battlefield, while being

flexible and survivable enough to support troops advancing in the wake of

nuclear attacks. The problem of achieving a smoother and more rapid tran-

sition to the use of nuclear weapons by rocket troops is of continuing con-

cern. Solutions for effectively supporting breakthrough operations while

minimizing, risk from sudden nuclear attack emphasize better target acquisi-

tion and fire control procedures, improved reconnaissance, greater mobility

of artillery units, and more intense concentrations of shorter duration.

fc) /МПГПРИMIIП The Struggle Against Enemy Nuclear

Means.

Ы

The anticipated US fielding of enhanced radiation (ER) warheads, especially

for 155-mm systems, in view of their numbers, substantially magnifies the

problem of finding and destroying enemy nuclear means. The much improved

effectiveness of ER rounds over standard nuclear rounds for the 155-mm

system makes their effective targeting and destruction in the non-nuclear

phase a much more critical requirement. We expect the Soviets to attempt

to meet this requirement by focusing more reconnaissance assets on the

task, and by enhancing the quantity of nuclear and non-nuclear fire means

intended to destroy 155-mm systems. Conventional SS-21 and SS-23 missiles

are expected to he included in the assets to be targeted against Efl-capable

systems.

(d) (S/NOFORN/WNINTEL) Fire Support Phases. Soviet offensive

procedures divide the destruction of enemy fire into at least three phases:

preparatory fire for the attack, fire support-of the attack, and close fire

support for troops advancing into the depth of the enemy positions.

Heightened emphasis on rapid movement forward from deep rear areas and

2-10

0369

SECRET

commitment from the march suggest that specific fire support to that phase

of operations is also required. This seems particularly important with

respect to formations such as operational maneuver groups, which are

intended to move' rapidly through gaps formed in -enemy formations and

operate extensively in enemy rear areas. Whether or not the Soviets per-

ceive a requirement for a fourth phase of fire destruction, they are con-

cerned with transitioning rapidly and smoothly from one phase of support to

another. High priority is placed on improving automation of the fire

destruction system to permit automated fire commands and selection of the

optimum weapon mix.

(e) {S/NOrORN/WNINTCL) Massive Fires. Because of improved

troop mobility, greater armor protection, and better artillery capabili-

ties, the role of massive artillery fire has increased in recent years.

Emphasis is being placed on measures to permit a higher volume of fire to

strike given targets rapidly. Procedural steps include attention to hasty

artillery preparation, using the overlapping fires of several artillery

groups on single targets. The need for a single powerful artillery strike

on a given target, as opposed to a longer-lasting but less intense attack,

has been stressed. Current high mobility offensive operations demand that

massive fire be sudden, accurate, fully coordinated with actions of

advancing troops and supporting air power, and preceded by minimal prepara-

tion time. Principal targets for massive fire would include tactical,

nuclear weapons, concentrations of tanks, antitank weapons, and mechanized

infantry, self-propelled artillery, centers of enemy resistance, counterat-

tacking enemy forces, fire support helicopters in basing areas, and.others.

Centralized command of reinforcing fires, more self-propelled artillery to

permit easier concentration and dispersal, and growth in the quantity of

both divisional and non-divisional artillery will help achieve the require-

ments for higher-intensity fires. Non-divisional artillery batteries are

expected to increase from 6 to 8 tubes, and the artillery battalion will

probably become the basic firing unit, as opposed to the battery.

(u)

(f) (S/NQFORN/WNINTEL) Fire Support of Mobile Operations.

More responsive on^call fire support for troops advancing into the enemy

depths is also required. Supporting artillery is to be more mobile and

flexible, to permit maneuver units to use more fully their enhanced

maneuver capabilities. The concept is to preempt enemy artillery units, in

opening, up artillery fire, and to permit no lulls when fires are hieing

shifted. The increase in tube artillery within maneuver regiments and the

introduction of 82-mm mortars and 85-mm antitank guns will help to achieve

more-effective suppressive fires for maneuver units operating in the enemy

depths. Fuller integration with attack helicopters and more emphasis on

direct fire for these functions, to reduce anwunitlon expenditures, may

also be expected.

(u)

(g) (-S/NOFQRN/WNINTEL) Other Key Requirements. The Soviets

pay great attention to the need to find better ways of suppressing enemy

antitank systems. This is a primary motivation that cuts across al Г facets

•2-11

Regraded UNCLASSIFIED on

31 March 2014

by USAINSCOM FOIZPA

Auth para 4-102, DOD 5200-LR

0370

SECRET

of fire supportK and it is -being approached in an integrated manner. They

are also seeking more fire support efficiency through ammunition improve-

ments and better use of SR8M systems in the war's conventional phase,

possibly including infrared-seeking sub-bombiets and cratering rockets.

Special, attention is also to be given to fires under mountain and night con-

ditions. Artillery fire support is among the areas of greatest potential

near-term and mid-term improvement, due to the large numbers of new systems

and associated capabilities that have recently begun deployment or are

awaiting deployment in the near future.

(9) Air and Air Defense. The Soviets are in the

process of integrating field force air defense and national air defense into

a single air defense structure that will improve theater capability,

increase operational flexibility, and enhance command and control. They

perceive a requirement for better theater-level integration of air defense

among Warsaw Pact countries. This is motivated by improvements in NATO

offensive aviation capabilities and by the expectation that the future

battlefield will be increased in spatial scope. Air defense integration is

part of a broader strategy that calls for rapid concentration of forces on

major theater axes through more responsive regrouping of major air and

ground formations over longer distances. Warsaw Pact forces will coordinate

both field force air defense operations and national air defense operations

along major theater axes in succession. They seek to achieve air supremacy

sufficient to maximally reduce NATO nuclear potential, |

Ы

________________________________________________________________| Further

advances can also be expected in Soviet SAM guidance systems and in missile

system containerization.

•(Ю) (U) Rear Services Support

(a) During the past decade Soviet capabilities for

logistical support of their operational concepts have grown steadily.

Whereas in the 1960s it may have been accurate to describe Soviet transpor-

tation, maintenance, and supply structures as sparse, this is no longer the

case today. To some extent, this perception was based on focusing,

incorrectly, on the divisional structure and overlooking the fact that the

Soviet concept is to concentrate support at echelons above the division.

Today Soviet forces are' well supported logistically in terms of transpor-

tation, maintenance and supply organizations, and equipment.

(b) (U) Nevertheless, Soviet leaders are very concerned about

the volume .of support required to sustain forces under modern combat con-

ditions. MSU Orgarkov has elaborated recently on the increasing materiel

requirements of modern warfare.7 He notes that current technical and rear

services requirements are in no way comparable with those of past wars.

2-12

s

0371

secret

Materiel requirements have risen "tens of times." The volume- of repair

required has grown many times and the nature of repairs has -changed. This,

in turn, is said to require improved organization of technical support and

to increase the-importance of the work of the deep rear of the -country,

which must be able to more-rapidly replace losses of "an enormous quantity

of combat equipment and weapons."

fa)

(c) (5/N8F0RN) Another chief concern of Soviet logistics plan-

ners is to Improve the rapidity with which the rear services structure, much

of which is in cadre status in peacetime, can be mobilized in a crisis.

Other important requirements are to improve standarization of equipment,

thereby simplifying maintenance and resupply; to increase the maneuver-abil-

ity of the operational (fr-ontal). rear; and to make use of the latest tech-

nology to plan and manage rear services activities.

(d) (~S/PI^?ORN) The Soviets and NSWP have devoted considerable

effort toward developing an automated rear service support system. By the

late 1980s or early 1990s, a computer network will be established that will

tie together Soviet ground force logistics from regiment to MOD-controlled

fixed computer centers. This system-will permit Soviet logisticians to:

fa)

2 (R/hoFuRN) Monitor materiel inventories and expendi-

tures.

Z (S/NO^Jrm) Determine materiel requirements for -opera-

tional concepts and recommend which plans are most

feasible from a logistic point of view.

fa)

£ ("S/NOfeRhb) Plan an-d implement transportation movements

using the most efficient modes and routing.

fa) '

£ (S/NQF6RH) Optimize the deployment of support units:

maintenance/ recovery, medical, engineer, and others,

based on projected requirements.

Full implementation of the rear service subsystem will significantly reduce

time requirements and enhance the effectiveness of ground forces support.

It is estimated that , time may be reduced from 48-72 hours to ^6-8 hours for

planning materiel support of a front offensive.

(11) (U) Command and Control

(a) The high speed, fluid battlefield envisioned by the

Soviets will place great demands on command and control. Increased mobility

and weapons effectiveness will result in frequent and radical changes in

battlefield situations, particularly when nuclear weapons are employed.

Vast amounts of combat intelligence will have to be collected, processed,

and disseminated responsive operational courses of action conceived,

Regraded UNCLASSIFIED on

31 March 2014

by USAINSCOM FOL'PA

Auth para 4-102, DOD 5200-1R

2-13

SECRET

0372

SECRET

evaluated, and directed and weapons systems targeted—all in a minimum of

time if fleeting opportunities for tactical success are not to be lost. The

problem is particularly critical for the Soviets if they are to implement

successfully their doctrine of preempting a -NATO first-use of theater

nuclear weapons. Minimizing strike reaction time is essential if elusive

targets such as nuclear-capable artillery and missile units are to be

destroyed between the time the decision is made to use nuclear weapons and

their actual employment.

(uj

(b) (4) The Soviets have long been concerned that the effi-

ciency of the decisionmaking and control processes has lagged behind the

growth of mobility in maneuver units. Control procedures are thought to

have become too slow from the identification of a requirement to the

issuance of unit orders. The most prominent means of compressing the

required time for planning and control procedures in the 1990s would -be an

integrated, real-time, automated command support (ACS) system. A fully

developed ACS could:

2 (U) Reduce significantly staff planning and

command decisionmaking time.

2 (U) Permit more-sophisticated consideration of

alternate operational and logistic problems.

2 (0) Improve and speed the collection, processing,

and dissemination of intelligence data and expand

access to it.

£ (U) Enhance the management of resources.

(c) The Warsaw Pact has been engaged since the 1960s in a

multinational, effort to provide their forces with automated support of com-

mand, control, and communications. Parts of an ACS system are now opera-

tional, particularly in the area of air defense and artillery fire control.

A completely developed ACS system will probably be deployed to ground force

tactical commanders in the early 1990s.

(u)

(d) (5) The structure of the Soviet ACS system is likely to be

along the lines of a conceptual plan developed by the Czechs, in response to

Soviet tasking, in the mid-1960s. This concept, called MODEL, integrated up

to 30 operational functions into six groupings supported by a centralized

ACS system. These systems are:

1_ (U) Strike activities—all means of striking enemy

ground forces.

2 (U) Troop maneuver—all ground troop movement activi-

ties not included in the strike category.

Regraded UNCLASSIFIED on

31 March2014 2-14

by USAINSCOM FOI/PA

Auth para 4-102, DOD 5200-lR

&ECPFT

0373

Ut-twKL. I

I-

3. (U) Reconnaissance—serveil lance -and reconnaissance

activities of individual services incliiding intelli-

gence activities.

£ (U) Supply—materiel support activities and facilities

of all branches of service, including logistic transpor-

tation. .

£ (U) Air defense-activities and facilities of the

entire air defense system.

£ (U) Political administration—activities of the

political and military service structure.

(u)

(e) The ACS system may feature control computers at each

operational headquarters from front to division designed to interface with

the decisionmaker and pass subtasks to specialized computers. Computers

would be at regimental level, but not necessarily for use in a control role.

Battalions would transmit and receive data through computer terminals.

(u)

(f) (S/NOrORN) In the area of strike activities, a completed

ACS system would enable commanders from regimental level on up, through

their respective Chiefs of Rocket Troops and Artillery (CRTA), to calculate

quickly total fire requirements based on the norms for various targets,

weigh the suitability of available strike means, and select the most econom-

ical means based on weapons capability. Likely programs would:

£ (U) Formulate and disseminate fire support plans.

£ (0) Furnish the number and readiness condition of

friendly strike means.

3 (JJ) Provide the categories and parameters of enemy

targets.

£ (U) Calculate the possibilities for various engage-

ment combinations.

5 (II) Pass logistic status reports and requests.

(g) Intelligence collection, collation, and dissemination

is an area particularly suitable for automation. A fundamental problem

inherent in the Soviet intention to preempt a nuclear strike is tracking

highly mobile delivery systems so they can -be attacked prior to employment.

By the 1990s, the Soviet ACS system will be much more capable of accepting

data directly from a wide variety of sensors, although information from some

may require manual input. Target location data will probably be passed

quickly and efficiently up and across echelons -digitally in the ACS

intel 1igence/reconnaissance (I-R) subsystems. Input and output will be made

Regraded UNCLASSIFIED on

31 March 2014 3-15

by USAINSCOM FOIZPA

Auth para 4-102, DOD 5200-1R SCCfiET

0374

by subsystems used in other functional areas such as strike, air defense,

maneuver control, and aviation. Information collected from assets other than

those under control of the ground force chiefs of reconnaissance--!.e., from

from aviation, artillery units, and maneuver elements--wiH therefore be

readily available to ACS users. Tactical level units down to at least

regiment, and probably battalion, will be able to access the system for data.

(h) jjt&f Sensor systems available to the Soviet ground force

commander by the early M90s will include side-looking airborne radar with a

real-time downlink. These systems will provide data on moving vehicles and

other targets within the tactical commander's area of responsibility,

including location and direction of movement. Other sensor systems will

also put real-time data into the ground force I-R subsystem. Among these

will be TV target acquisition/identification sensors with a low-light-level

capability, mounted on a variety of airborne platforms— e.g., helicopters,

tactical aircraft, and drones. Г

bl

2-16

0375

SECRET

3. (U) Footnotes

1. "Printsipy Voennovoy Iskusstva" (Principles of Military Art)" -by A.A.

Sidorenko, Sovetskaya Voennaya Entsiklopediya (Soviet Military Encyclopedia),

Volume 6 (Moskva: 1978)..

2. Ogarkov,N.V., Always Prepared to Defend the Fatherland, p.31, Moscow,

1982.

3. "For Our Socialist Motherland: Guarding Peaceful Labor," by MSU N.

Ogarkov, Kommunist, No. 10, July 1981.

4. Ogarkov, Always Prepared to Defend the fatherland, p.25.

5. The name "operational maneuver groups of the Army" is found in the

Polish open source journal, Review of Air and Air Defense Forces. June 1981.

During 1981, discussion of mobile groups, deep operations, operations of

groups of fronts, and other related concepts gained currency in Soviet open

source literature. See especially the December 1981 issue of

Voenno-Istoricheskiy Zhurnal (Military Historical Journal). This open

source discussion illuminates the historical roots from which DMG concepts

were developed.

6, Agility is used in the sense meant by Beaufre: "....The combination of

mobility and the reaction capabilities: information, decision, transmission

of orders, execution." See Andre Beaufre, Strategy For Tomorrow, footnote,

p.29, Crane, Russak & Company, Inc. (New York: 1974).

7. Ogarkov, N.V., Always Prepared to Defend the Fatherland, p.Z9.

Regraded UNCLASSIFIED on

31 March 2014

by USAINSCOM FOIZPA

Auth para 4-102, DOD 5200-lR

NOTE: The reverie side ol thii

page ii blank.

2-17

SECRET

0376

SECRET

CHAPTER 3

SOVIET CAPABILITIES TO MEET WESTERN THEATER

RE-QUIREMENTS (THROUGH 2000) (U)

1. (U) Adequacy of Force Structure to Accomplish Required -Operations in

the Western Theater.

a. (5/N^ORN) The Soviets appear to be fairly satisfied with the total

quantity of the ground forces at their disposal for planned operations

against NATO. They are concerned with the readiness -of these forces to par-

ticipate early in offensive operations. This is particularly applicable to

the forces in the Western Military districts of the Soviet Union, which are

expected to form the initial reinforcing fronts used to extend quickly the

success of first echelon fronts that have penetrated deep into NATO rear

areas. The nature of Soviet operational concepts, with the -premiumplaced

on keeping NATO off balance and unable to react to offensive pressure,

demands that offensive momentum be maintained through campaign completion.

The Soviets, therefore, must be concerned with the readiness of Western ND

forces to conduct effective offensive combat operations early in the war.

This concern is heightened by fears about the reliability of their NSWP

partners, by the growing gap in capabilities between some NSWP forces and

the better Soviet divisions, and by the growing realization of the immense

attrition expected to occur.

b. (S/l^OFORN) For these reasons, the Soviets probably wil T undertake a

long-term program to gradually heighten the mobilization readiness of their

forces opposite NATO. Taking into consideration manpower constraints and

the need for force increases in the Eastern Theater, a likely way to

increase readiness would be through a combination of measures:

(u)

(1) (S/NOFOR-N-) Upgrade selected Category Ш divisions to Category

II status; , .

(u)

(2) (S/N0F6RN) Mobilize as low strength Category III divisions

some existing inactive or mobilization base divisions;

(u)

(3) (S/NOFORN-)' Upgrade the Vyborg Corps and presently under-

strength WTVD armies to full size, and establish an additional army in the

Baltic MD from available MD forces;

(u)